It is fascinating what unexpected discoveries can be made in the McGill University Archives. This month, during my graduate studies internship with MUA, I discovered a Soviet spy. Working at McGill University. During the Second World War.

It all started with subject files kept by Robert Collier Fetherstonhaugh, Director of McGill’s War Records office. Fetherstonhaugh had gathered extensive war-related material that is now showcased on the McGill Remembers Project website . The Project now provides access to digitized archival records which profiles members of the McGill community who contributed to the Second World War effort.

Some of Fetherstonhaugh’s old subject files (along with issues of the Stars and Stripes newspaper from 1915/1916 and other fascinating items) had recently found their way from the basement of Redpath Museum back to the MUA department and I was tasked with inventorying them. The subject files cover a wide range of topics, including sea sickness research, university naval training, and radio technicians courses. Each file is painstakingly labeled and numbered, all in Fetherstonhaugh’s distinct rolling penmanship.

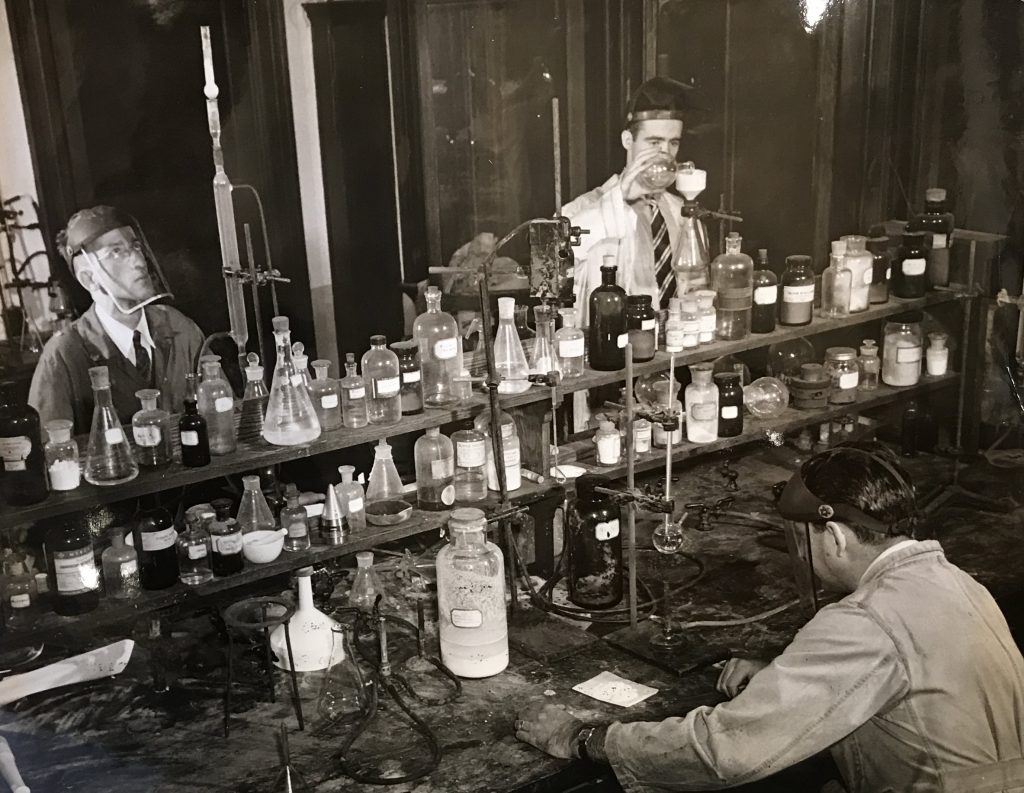

Dr. Raymond Boyer (back) and colleague, working on developing RDX. Photo credit: McGill University Archives, Canadian National Film Board. November, 1943

The file that really grabbed my attention was marked “R.D.X. (explosive)”.

Curious, not your usual subject matter. So, I looked up RDX on the internet. It is considered the most powerful military explosive and was used in the Second World War by both the Allies and the Axis powers, replacing TNT from the First World War. During the 1940s, researchers and scientists in the United Kingdom, United States, and Canada worked together to develop its production for use on the front lines.

Fetherstonhaugh’s RDX file contained, in addition to several newspaper clippings from 1943, three large black and white photographs from the Canadian National Film Board. The photographs document the McGill University’s chemistry lab working on the development of RDX. The notes added by Fetherstonhaugh mention only one person: Dr. R. Boyer. Again Fetherstonhaugh’s crisp handwriting graced the page with his McGill Remembers information: “Dr. Raymond Boyer, BSc ’30, PhD ’33; Lecturer in Chemistry. McGill University.”

It is clear from several editorials in the Montreal Gazette, clipped and saved by Fetherstonhaugh, that the collaborative work being done by the McGill University chemistry department during the war was highly valued and a source of great pride. Working with RDX production materials (including paraformaldehyde and ammonium nitrate) was potentially life-threatening, and these men were considered heroes for their bravery and dedication.

As the Montreal Gazette noted on November 6, 1943, the Canadian contribution to RDX development was a “story of Canadian achievement, of international cooperation unique in the annals of science. It is a story of modest professors who gambled with death – and won.”

But this story of bravery and national pride quickly changes tones.

After searching for more information about Boyer online, I suddenly feel like I am reading a Tom Clancy novel. How is it that one of the first online entries for Dr. Raymond Boyer is from the Canadian Human Rights History website, with unsavory details of civil rights violations, and things such as the Gouzenko Affair and the Kellock–Taschereau Commission? Well, in 1946, Dr. Boyer was arrested, tried, and convicted of giving secret information to the Soviets about the production of RDX. “Holy Soviet Spy, Batman!”

Early on in the Second World War, the Canadian Communist Party was deemed an illegal organization. Members of the organization had been working with the Soviet secret police to provide military intelligence information to the USSR including tank delivery quantities, and details about explosives (such as the RDX which was being studied at McGill University).

In June, 1946, the Kellock–Taschereau Commission was established to unearth the exact workings of this spy organization. Agents had been planted in the Soviet embassy in Ottawa, and there were many connections with Canadian scientists. They had been using intriguing code names like Prometheus, Gray, and The Professor. In all, 16 suspects were charged by the Commission with conspiracy to violate, or violation of, Canada’s Official Secrets Act. Of the suspects, six of them were McGill graduates – all men holding various undergraduate, graduate, and PhD degrees in the scientific fields of chemistry, engineering, physics, geology, and radioactivity.

Raymond Boyer’s McGill University Staff Card. McGill University Archives. Photo credit: Ianna Breese

What was the motivation of these individuals, so many of who were highly educated, to participate in a conspiracy to betray their country and supply a foreign power with secret war-time information? Boyer himself (aka The Professor) testified to the Commission that he had shared the information because he felt it would contribute to “international scientific collaboration.” (Kellock–Taschereau, p 74) despite having taken Canada’s oath of secrecy.

If the admiration of those at the Montreal Gazette in 1943 were any indication, Boyer and his colleagues truly believed in the collective work of the scientific community. They put the collaboration between scientific colleagues above any reservations that sharing sensitive information might risk their government’s edge in the war or jeopardize the safety of fellow Canadians.

Front page of the Kellock-Taschereau Commission Report, [Ottawa : Privy Council], June 1946. http://publications.gc.ca/

The ultimate downfall for Boyer and his colleagues was that their collaborations and transgressions took place during a time of war.

Under the Kellock–Taschereau Commission, the Canadian federal government invoked its wartime powers and proceeded to violate suspects’ rights. Habeas corpus was suspended, the suspects were denied legal counsel, and they were detained and questioned for weeks. A handful of the commission’s suspects were charged simply because they knew a person who had been involved.

Even if these suspects were eventually acquitted, their reputations were forever tainted. As is still clear today, as seen on the Canadian Human Rights website and similar others, the overwhelming tensions of wartime and fear of Communism tainted the proper due process of law and representation.

Of the six McGill University graduates who were charged by the Commission, Raymond Boyer, Durnford Smith, and Harold Gerson were found guilty and each sentenced to 2-5 years in prison.

And so, Dr. Boyer, a man who had risked his life to help his country and its allies in the war effort, seems to have faded away silently. Were it not for his unwavering willingness to share his scientific knowledge, and his sense of duty to the collaborative research community, would we would still be praising his accomplishments, his bravery, and his dedication to the cause?

McGill University Chemistry Laboratory. RDX research. Photo credit: McGill University Archives, Canadian National Film Board. November, 1943

By Ianna Breese

McGill University, School of Information Studies, 2019 MISt Candidate

Sources:

McGill University Archives – War Records

Government of Canada, Kellock–Taschereau Commission, [Ottawa : Privy Council], June 1946, http://publications.gc.ca/site/eng/472640/publication.html

Wikipedia, Kellock–Taschereau Commission, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kellock%E2%80%93Taschereau_Commission

History of rights, Canada’s Human Rights History, https://historyofrights.ca/

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.