By Yves Lapointe and Adria Seccareccia[1]

Founding documents often serve as symbols of collective identity. Over time, they are frequently referenced in conversations regarding changes to this identity. McGill University’s founding documents are no different. The 1821 Charter and its subsequent version function as a crucial record of the institution’s history, but also chronicle perceptions on how to run a university successfully. So, as an archivist, what do you do if the original 1821 Charter is not held by McGill’s Archives? How do you begin your quest to locate the original founding document? Well, you look for clues, of course, part of which entails developing a historical understanding of the political and social context of the time.

What is a Charter and how was McGill’s created?

A charter is a legal document that establishes the founding of an institution, organization, company, or, in this case, a college. Often, charters will outline the purpose of the institution, how it will be governed, and who will run it. The history of McGill’s Charter begins in 1801, when the Royal Institute for the Advancement of Learning (RIAL) was created by a statute of the Province of Lower Canada, which authorized the Governor of the Province to appoint school trustees. The volunteer-run, Protestant organization was dedicated to increasing secondary and post-secondary education in the Province in response to pressure from English-speaking Montrealers. Trustees were authorized to purchase, receive, possess, and retain lands and property for schools.

0000-1377.03.1

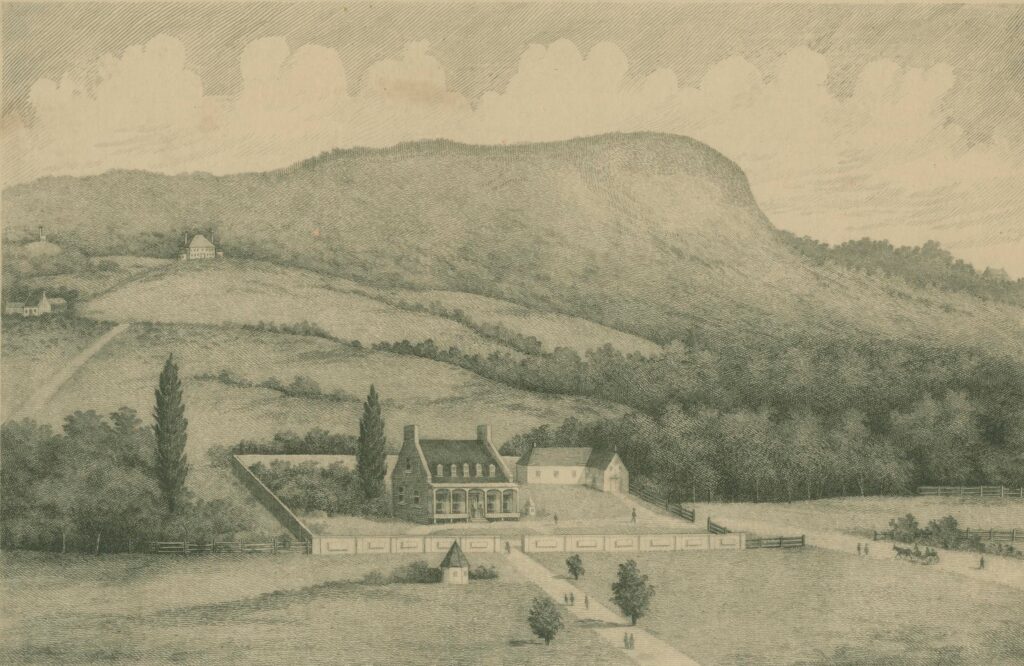

Upon his death in 1813, James McGill left in his Last Will and Testament the bequest of Burnside, his 46-acre farm, to the RIAL. However, Burnside would remain in the custody of estate executors until a stipulated condition was met: within ten years of McGill’s death, the RIAL would be required to establish a University or College in his name. McGill further bequeathed the sum of £10,000 as an endowment to cover expenses associated with the establishment and maintenance of the College. If the College were not established within the 10 years, the property and funds would revert to James McGill’s heirs.

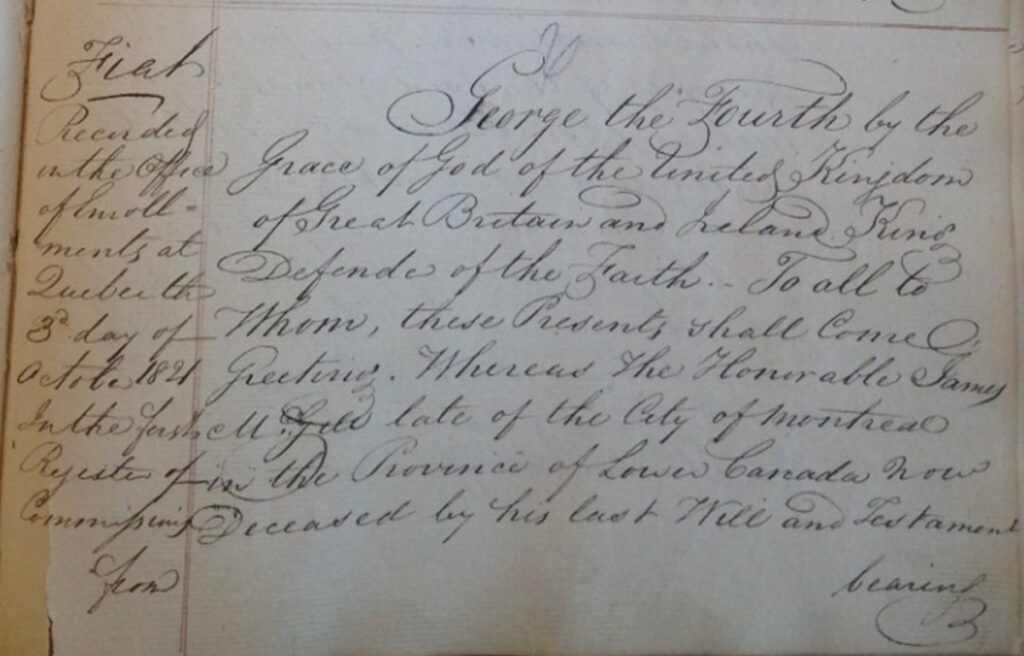

The RIAL therefore secured a charter for the incorporation of the College. After Burnside was transferred to the RIAL by the estate’s executors in 1820, a Royal Charter was granted by Lord Dalhousie, then Governor General of Canada, on March 31, 1821, thereby establishing “McGill College.” The Charter declared that the “… College shall be deemed and taken to be a University.” It also outlined the appointment of a governing board and stated that the Visitors of the College were to be comprised of members of the RIAL.

The mystery of the original Charter

One would assume that McGill’s Charter would be held by the McGill University Archives (MUA), right? Well, yes, but not at that time; the MUA was not established until 1962. The location of legal documentation like this depended on where the authorities at the time kept their records. Moreover, there can be several different versions of legal documentation over time. So, where is this 200-year-old document today and why has it taken this long to track it down?

Interestingly, the hunt for the 1821 Charter can be traced back to 1967 when the MUA received a certified copy of the Charter, issued in 1833 by the Secretary and Registrar of Lower Canada. This copy was found in the vault of Christ Church Cathedral in Montreal[2] and returned to then principal Cyril James. As to how it wound up at Christ Church, a 1940 Montreal Gazette article speculated that Rev. John Bethune, rector of Christ Church and principal of McGill University (1835-1846), kept the Charter at the church for safe keeping.

As it was a certified copy, questions arose regarding the location of the original Charter. Was it ever given to the College after it was granted in 1821? Why was a certified copy issued in 1833? Tracking down the original Charter became a goal for the Archives, with the University’s Bicentennial as a deadline for solving the mystery.

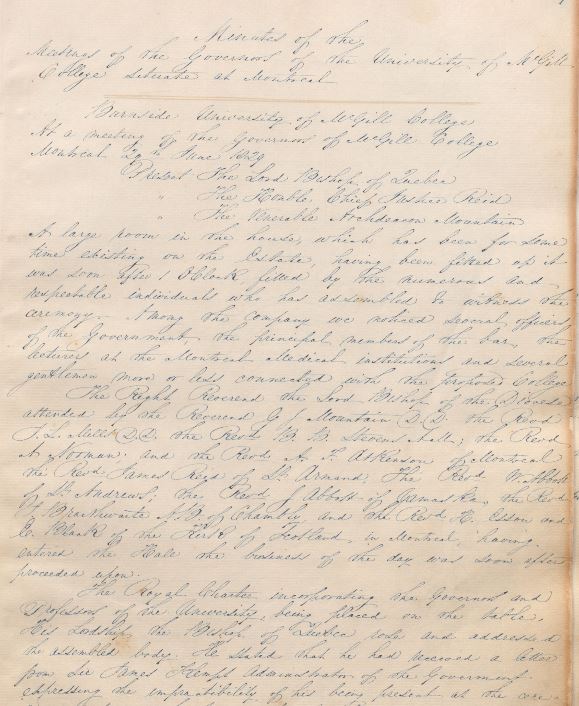

Since the Charter was granted by Lord Dalhousie, the first step was to figure out if it had ended up in England or if it had remained in Lower Canada. If it was in England, a likely location today would be the National Archives of England. Yet, entries in the Governors’ of McGill College minute book, indicate that the Charter was at one point on McGill premises. It was on display at the College’s opening ceremony on 29 June 1829. Furthermore, several entries, from 1833-1835, document conversations about modifying the Charter. A closer reading of the 1833 certified copy also suggested that the Charter was close at hand. The copy resembled an enrolled conveyance of land for charitable purposes, which is, simply put, the registration of a property transfer from one party to another. A clue! There could be a potential entry in the First Register of Letters Patent, held at Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec (BAnQ).[3]

The hunch that the 1821 Charter was close to home became very promising. If the Charter had been issued as a letter patent under the Great Seal of Quebec (or Lower Canada) and had been recorded in the register, it was possible that no enrolment had been made in Britain. Therefore, it would not be held by The National Archives of England. Enquiries at BAnQ, revealed that all pre-confederation registers are held at Library and Archives Canada (LAC). We were getting closer! LAC confirmed that there was an entry in their registers for the 1821 Charter. Unfortunately, the current pandemic conditions, have put our hunt on pause. We hope a trip to LAC is in our near future and we are curious to see what clues we can find in their holdings. Hopefully, these will lead us to the original Charter.

A final thought: The 1852 Charter

Remember how we said that there can be several iterations of legal documentation over time? Well, the story of McGill’s Charter did not end with the 1833 certified copy. On July 6, 1852, Queen Victoria granted a Royal Charter to the University, superseding the 1821 Charter. This new Charter demonstrated a different vision for how to effectively run a university and introduced significant amendments. For instance, members of the RIAL were to serve as Governors of the College, the Governor General of Canada was appointed as the Visitor instead of members of the RIAL, and the Governors of the College were granted the authority to create rules, ordinances, and statutes. So, although today we celebrate the 200-year anniversary of the original 1821 Charter, to this day the University is governed by the 1852 Charter. Sadly, we leave you, the reader, with the mystery of the 1821 Charter’s whereabouts still unsolved…but we hope to conclude this saga in a future article. Stay tuned!

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.