The Rare Books and Special Collections of the McGill Library houses about 250 medieval manuscripts in Latin and/or in European vernacular languages. While we do boast about a number of bound, spectacular exemplars of prayer books, choir books, and philosophical texts, the majority of the collection consists of fragments in the form of single leaves, bi-folium, excised decorated initials, and illuminated miniatures. Each item in McGill’s medieval collection is significant no matter how incomplete or how small the fragment. Even cuttings formerly used in bindings or on bindings of later works qualify as having intrinsic historical value. These orphaned parts are really part of a giant medieval puzzle, with the various pieces scattered around the world in institutional repositories or in private hands.

from a Breviary c. 1470, Rouen, Ms. 102

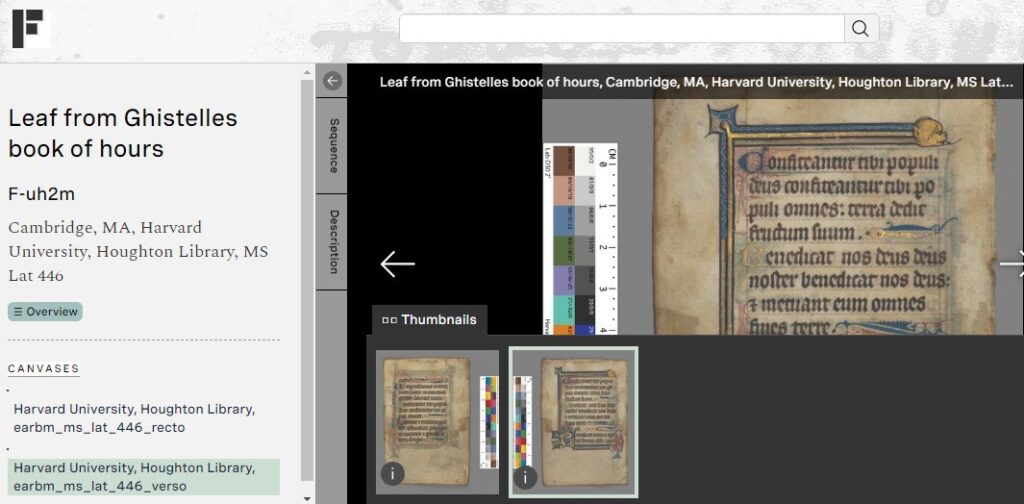

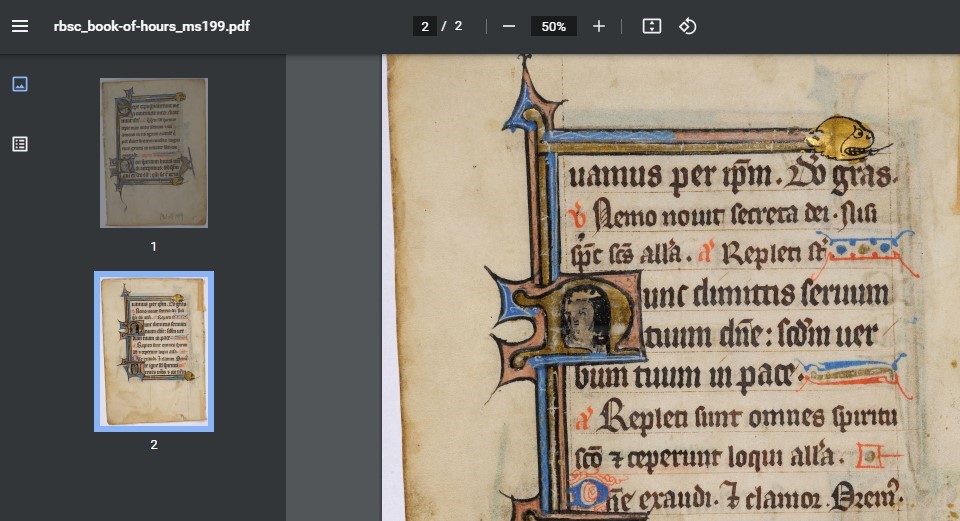

“Fragmentology” is a new approach to the visual gathering of such dispersed fragments in order to re-assemble the pieces of a codex. A digital platform is now available to apply collective energy into fitting the pieces of the puzzle back together again, which has an enormous potential for research. Fragmentarium is the name of a partnership of institutions gathered to develop the technologies needed to build “a common laboratory for fragments” and conduct research. It promises to yield digital versions from the original fragments, constituted from various holdings. This process will enable provenance research, the study of the circulation of manuscripts, and generate connections among researchers and curators. Thus a leaf holding comparable visual cues may be further investigated as a originating from the same or similar source. This fragment from the Houghton Library at Harvard holds a striking resemblance to one of McGill’s fragments Ms. 199.

Funded team projects like the one established for the McGill Books of Hours Digital Collection, are a crucial step in participating in digital puzzle-solving, starting with the digitization of the contents in high-resolution, and making them available on open-source platforms. Greg Houston, of McGill’s Digital Initiatives, has worked steadily to capture many of our unique collections. McGill’s twenty-five detached leaves inventoried in the Books of Hours project may soon find their place in the collective digital puzzle.

Likewise, an inter-university faculty-led chant music project has recently expanded their focus to include fragments on a collective site: Cantus: A Database for Latin Ecclesiastical Chant. Potentially, this will offer an equally rich online resource for fragment pairing. Apart from a few complete codices, the McGill Library supplied about 45 fragments in high resolution to team members Jennifer Bain (Dalhousie), Debra Lacoste (Waterloo), Julie Cumming (McGill) and PhD student Alessandra Ignesti. At the moment, the McGill chant codices and fragments have been largely published with just a bit more editing yet to do on the inventories and descriptions. These same scholars are offering up fragments that might be matched by peer investigators in the correlated Fragmentarium project. There are plenty of stunning examples from McGill to consider, such as Ms. Medieval 0078, with an elaborately decorated border and initial “B”.

Far from being dormant pieces of the past, there is a dynamic process of scholarship being accomplished with these precious materials. As research proceeds, we expand upon the descriptive entries in our Finding Aids and participate in the construction of knowledge. This process is happening at the project level and on more discreet levels. For instance, an herbal leaf dating shortly before 1400 was identified last year by an expert from Bologna as being part of a copy that the British Library is tracing and referencing.

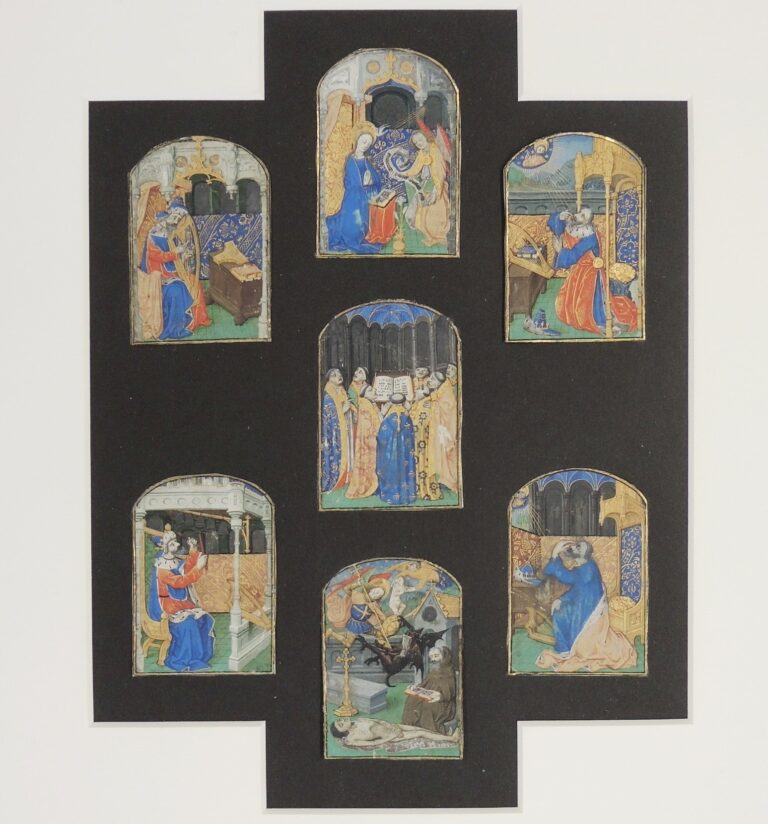

Fragments reap rewards. As collection curators discuss provenance of the fragments, it will bring into better focus the stories revolving around ownership and collecting of medieval artefacts, which are valuable to book and cultural historians. In the classroom setting, fragments lend themselves to more focused examination exercises. With a good cross-section of materials, displayed in advantageous ways in our teaching spaces, a comparative analysis of regional decorative styles (initials, borders, miniatures), page layout and scripts, is apparent almost in a single glance.

We owe our fragment purchases to the vision of one of McGill University’s first librarians, Gerhard R. Lomer (1920-1947), who mined the interest in the medieval era to launch a small museum of the book inside the McGill Library. Because Lomer’s acquisition of medieval manuscript material was primarily for the purpose of documenting the history of the book, much of the McGill collection consists of single leaves and fragments, usually chosen for their illuminations, decorations, script, or perhaps a binding, in the case of a codex. Lomer’s efforts played out in the 1920s to the 1940s, with library funds for acquisition and with the assistance of a number of bequests from the Redpath Family, particularly on behalf of Lady Amy Roddick, niece of Peter Redpath.

We are extremely grateful to past benefactors and current scholars, for enabling our future digital puzzle-making pleasure.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.