Philadelphia-based artist, Theodore Harris, insists on the power of visual art to reveal diverse perspectives, speaking of our collective past, present, and future in a contentiously shared world. Presenting as keynote at Culture Shock, a yearly event co-hosted by The Quebec Public Policy Interest Research Group (QPIRG) and the Student Society of McGill University (SSMU), the event explored the role of art in addressing challenges facing communities of colour, a topic to which Theodore Harris’ professional and personal life has been passionately dedicated.[1] This year, the McGill University Visual Arts Collection acquired its first work by Harris, a collage entitled The Long Dream, After Richard Wright (image 1). The work packs a mighty visual and political punch, providing an opportunity for our collections to grow as spaces to share, and hopefully better understand, diverse truths and perspectives.

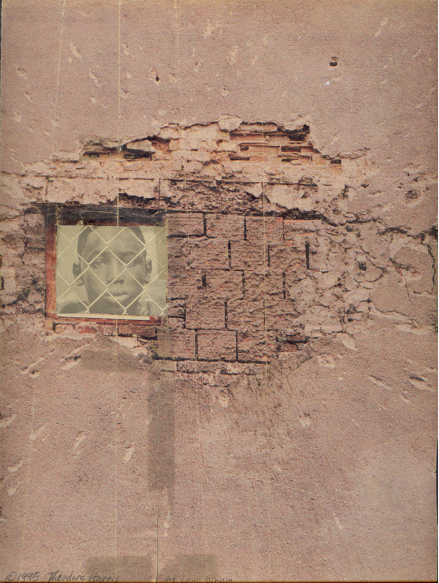

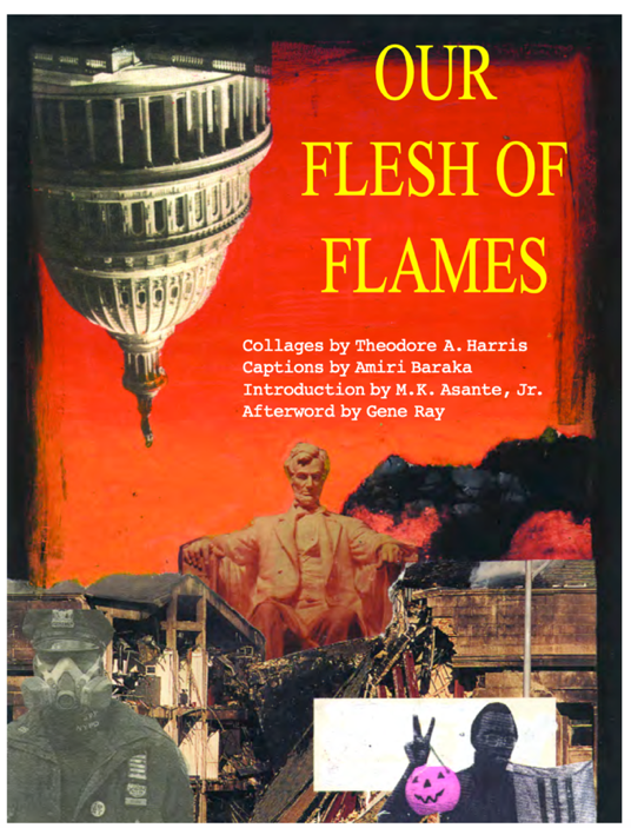

Containing a bricolage of ephemera and found objects, Harris’ collages have been described as “truthoscopic,” a term poet Amiri Baraka coined specifically for Harris’ work in the introduction to their collaborative book, Our Flesh of Flames (image 2).[2] In his work, Harris engages with both past and present, using the collage medium to create layers of meaning, compressing time and space to flip the original intentions of the image and reveal his truth. The VAC’s newly acquired work combines two images to form a compelling eyewitness testimony of Black experience. The image of the boy behind the fence was pulled from an advertisement for the movie Fresh (1994), while the image of the wall was found in a newspaper article covering a missile strike in Israel.[3] Mastering the medium, the effect of layering the two images one on top of the other creates a Trompe L’Oeil effect, tricking the eye into believing that the young boy is truly confined by the damaged wall.

In an interview with VAC staff in November, Harris explained the metaphorical meaning behind the work:

“In composition and form [The Long Dream After Richard Wright] is minimalist, just two images. You have a fence and a wall, hurdles this young Black man has confronted and must navigate in life. This work was made at a time when I was starting to cite or credit the poets, novelists, and essayists who influenced my work, and at this point I was writing poetry and manifestos that were just as important to my practice as my visual art.”[4]

Influenced by the self-reflective writing of prolific mid-century novelist, poet, and civil rights activist, Richard Wright, Harris’ visual works are profoundly autobiographical. The Long Dream, After Richard Wright, named after one of Wright’s novels, acts as witness to the racial injustice that the artist observed first-hand, and shares his testimony with the viewer through a compelling visual language. Art provides important visual evidence of racial inequality and, according to Harris, is a way of insisting that “I’m not making this up.”[5] Harris’ most recent series, Thesentür: Conscientious Objector to Formalism, develops the idea that “Black art is a way of documenting bodies,” a statement borrowed from poet, Fred Moten, that underscores the documentary nature of his collages (image 3).[6]

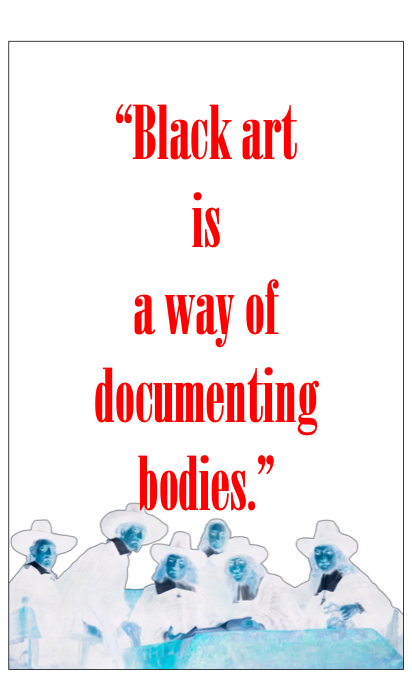

Image 3: Theodore A. Harris, After Fred Moten (Ghosts) Thesentür: Conscientious Objector to Formalism Series. 2020, digital image, collection of the artist. Image assistance by Emily Brewton Schilling.

Given the influence of literary giants like Richard Wright and Fred Moten, Harris reminds us that our libraries speak profoundly to our past, present, and future:

“For me, libraries, archives, and rare books can send you back in time, but you may find some things have not changed in the present you’re living in.”[7]

Thanks to the unique relationship between our rare collections, which are brought together under one unit (ROAAr), connecting Harris’ visual art with the literary works that influenced them becomes all the more relevant.

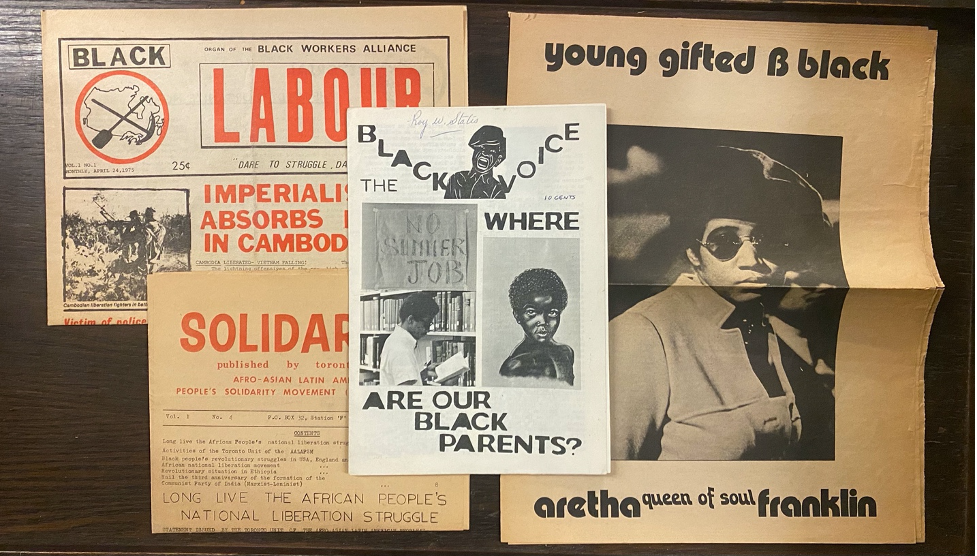

Further opportunity to see material evidence of Black activism, the kind of raw material that influences Harris, can be found in the Roy States Collection of Black History held by McGill Rare Books. Affectionately known as McGill’s Master of Ceremonies, Roy States was McGill’s Supervisor of Special Events throughout the mid-century era. States began collecting materials relating to Black history at the age of 15, and once owned Canada’s largest personal library on the subject.[8]

Roy States’ collection (donated to McGill in 1981 by his estate) contains rare first-hand accounts of grass-roots movements for racial equality in the 20th century, and between convocations and installation addresses, States compiled an international collage of Black experience. In addition to works by prolific writers like Richard Wright, hundreds of periodical and newspaper items reveal the nuances of States’ mid-century era of Black activism. Just as Harris predicted when prompted to think about the place of libraries in understanding our place in history, many of the challenges described in States’ collection carry messages that remain important in our present moment (image 4).

Both States and Harris gravitated towards libraries and archives as they sought inspiration for their work. When asked what sparked his interest in curating a collection on Black history, Mr. States answered:

“I suddenly realized I didn’t know anything about myself, my people, my own race. I began to look for information.”[9]

Now with a place in McGill’s library as a part of the Visual Arts Collection, The Long Dream After, Richard Wright adds an important visual perspective to States’ literary quest that began nearly a century ago.

By Hannah Deskin, Collection Manager and Registrar, McGill Visual Art Collection with special thanks to Theodore A. Harris

[1] Rosalind Hampton, “Art Must be Our Magic Weapon,” Montreal Serai, December 29, 2011, https://montrealserai.com/article/art-must-be-our-magic-weapon-a-conversation-with-theodore-a-harris.

[2] Theodore A. Harris and Amiri Baraka, Our Flesh of Flames (Anvil Arts Press/Moonstone Press, 2019).

[3] Theodore A. Harris, “The Long Dream, After Richard Wright” interview by Hannah Deskin, November 12, 2020, via electronic correspondence.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Theodore A. Harris, interview.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Ibid.

[8] “Roy States: McGill’s Master of Ceremonies,” The McGill Reporter, January 16, 1980 (Vol. 12 No. 16).

[9] Ibid.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.