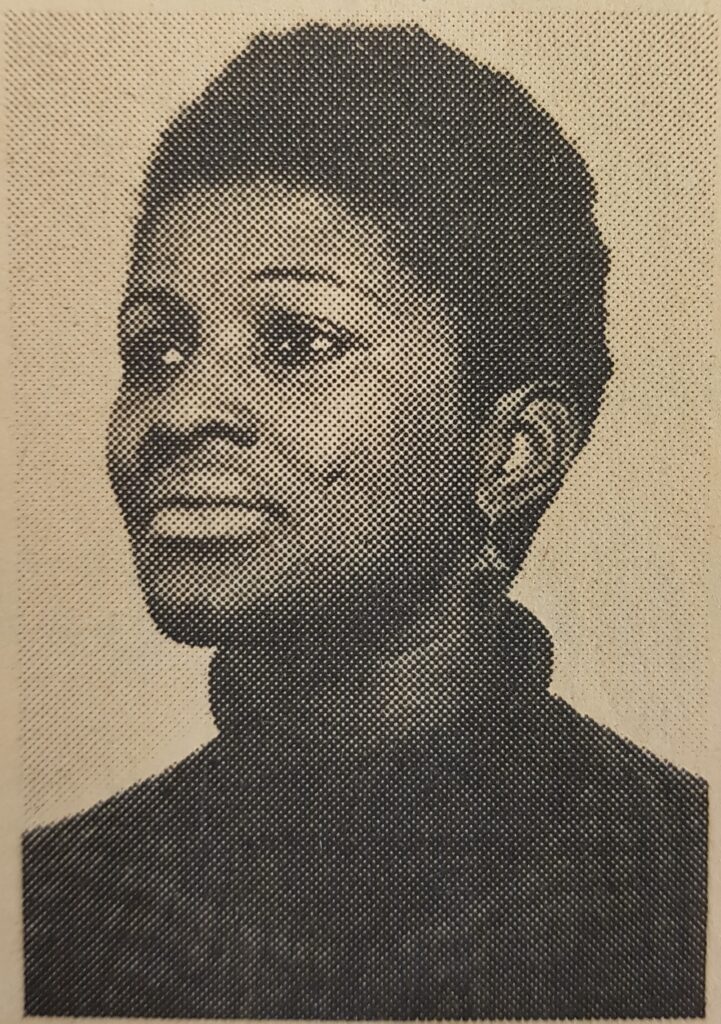

Dr. Barbara Althea Jones was born in Barataria, Trinidad in the late 1930s. She had a promising career in plant genetics, and was an accomplished poet, performer, and visual artist. She was also an activist, outspoken on the topic of racism and her experiences as a Black woman. She died suddenly at the age of 32 in Montreal, where she was working as an assistant professor in McGill’s department of genetics. Jones’s professional papers were given to McGill after her death by The Lady Davis Institute for Medical Research at the Jewish General Hospital.

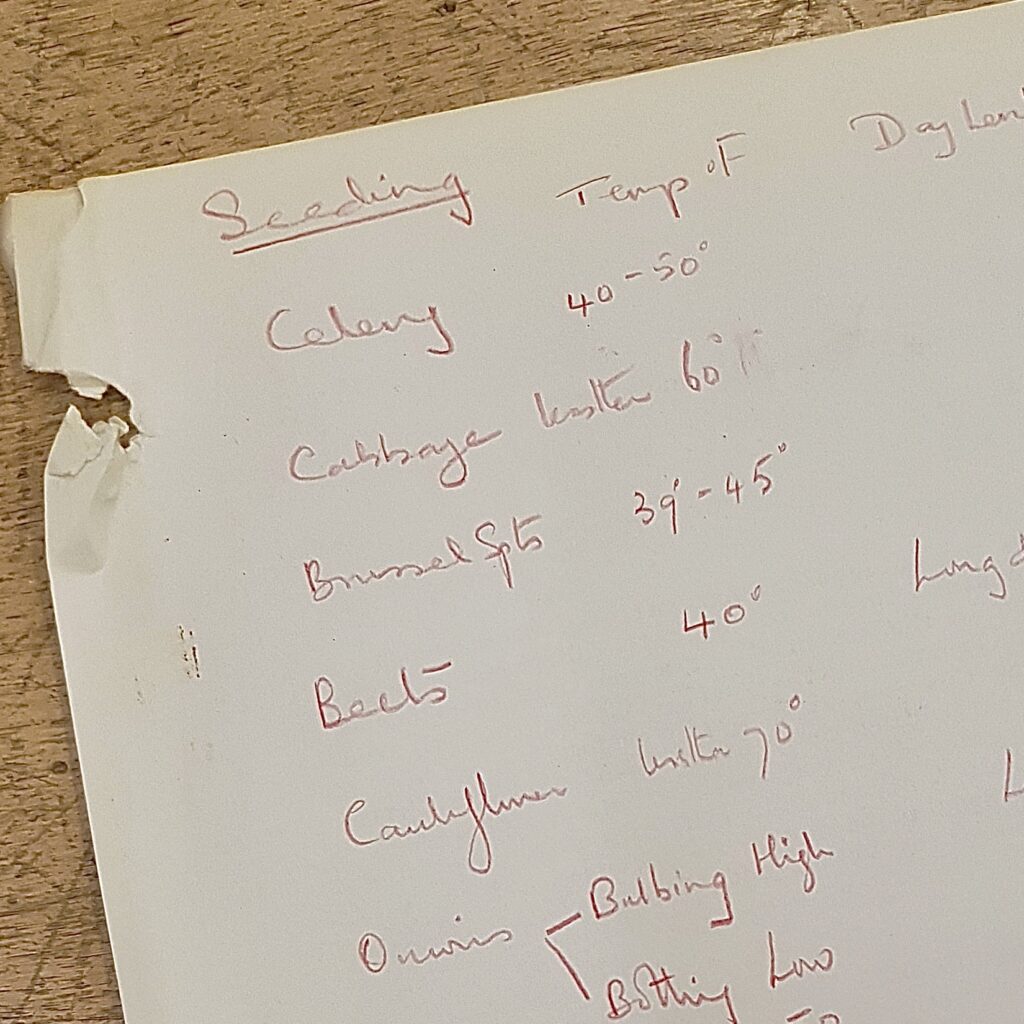

Jones was the first woman to graduate with a bachelor’s degree from the Imperial College of Tropical Agriculture in Trinidad (now the St. Augustine Campus of the University of the West Indies) and the first woman from the Caribbean to earn a PhD (Cornell University, 1965). After graduating with her doctorate in genetics – specializing in plant genetics and physiology – she taught for three years as an assistant professor at McGill, and also taught at Sir George Williams University (now Concordia University) and Marianopolis College. The McGill University Archives holds a fonds that documents her scientific career. The archival records from her time at McGill are extensive, ranging from the mundane (invoices for lab equipment, internal paperwork), to the professional (letters of recommendation that Jones wrote for students who worked for her, staff memos, detailed lab notes), and a bit of the personal (correspondence with colleagues at other institutions, scribbled notes in margins). All of them point to someone of great intelligence who had the respect of her peers and advocated for the workers she supervised.

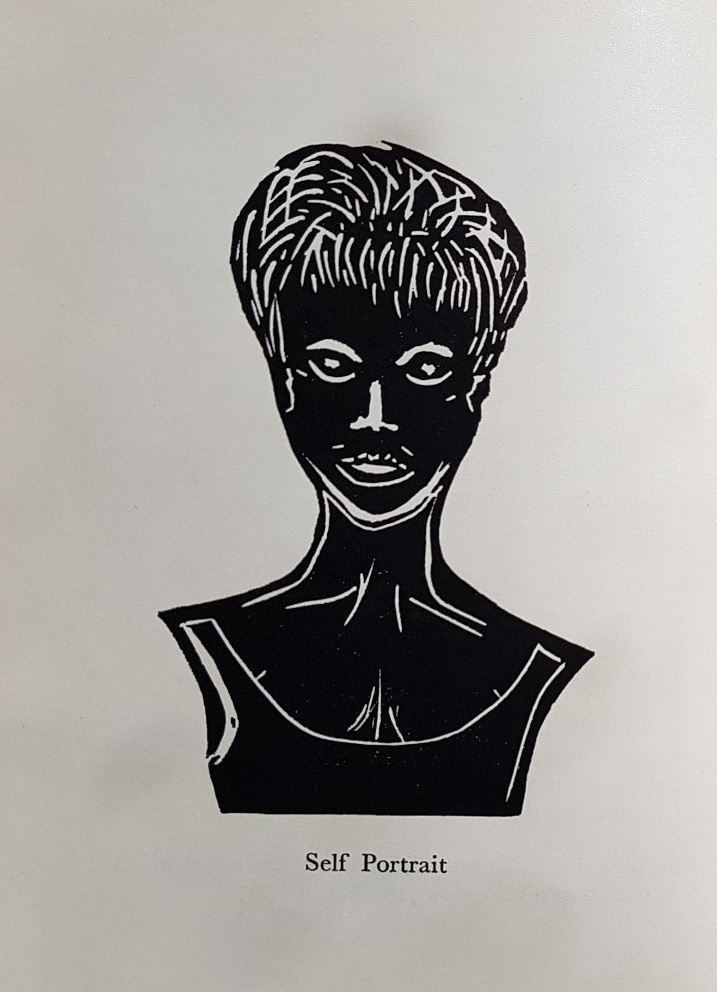

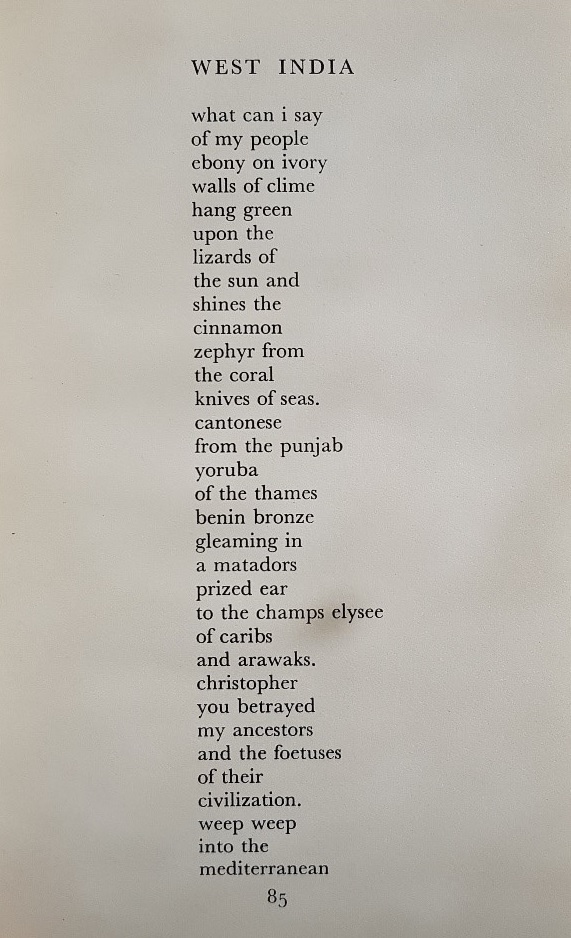

The Barbara Althea Jones fonds documents Jones’s life as a student and a researcher. For her artistic accomplishments, we turn to her published poetry. Among the Potatoes, one of her two books of poems, is a wide-ranging collection that touches on many topics, including her life as a student, love, home, mental health, and race. One of my favourite poems in the collection, “West India” (pictured above), celebrates her Trinidadian heritage, while condemning the violence of colonialism and slavery. Another poem entitled “Academia” is more humorous, lamenting that despite “money / down the / intellectual drain,” it is too late for students: “there’s no /return to / mediocrity / we’re hooked” (p. 57). Another explores her complex feelings about the Selma to Montgomery marches in 1965.

These poems are the most concrete evidence we have of her artistic life. Other traces include a note in her CV that she paints with oil and water colour, a list of her publications in literary journals, an ad in the McGill Reporter for “African Dream Song” – a reading she performed at the Museum of Fine Arts just a month before her death. While it is easy to wish for more documentation of this part of her life, these traces are enough to begin to imagine the role she played in the artistic communities of Montreal, Ithaca, and St. Augustine. Jones was not only a scientist – she was a “geneticist by vocation, a poet by avocation,” as she wrote in one of her CVs.

Clearly, Jones was outspoken about the experience of Black people through her poetry and performances, and her commitment to social justice extended into other areas of her life. In a CV, she wrote that her goals were oriented “Towards a new black man, towards the full realization of man’s consciousness and potential, and towards a new humanism.” This goal is reflected in a front-page article she published in the McGill Reporter in November 1968, where she provides historical context for the struggles faced by Black Canadians at that time. In an archived letter, she asks colleagues to donate scientific books “for universities of developing countries where for some reason it is difficult to obtain texts.” Once again, we can understand that these documents represent just a fraction of her advocacy work.

With a fonds like this that documents someone’s professional life, it is sometimes difficult to understand who they were as a whole person. However, there are enough clues in Barbara Althea Jones’s case to make it clear that she was an extraordinary human being.

By Aeron MacHattie, Archivist, Rare Books and Special Collections

Well done, Aeron! Very interesting.