This is an excerpt from the article entitled “Not a bad “Impression”: a fine Rembrandt Print in McGill’s Collection” written by Maria L. Brendel. It was first published in Fontanus, Vol 10 (1998).

In 1919 McGill received a seventeenth-century print from the estate of the Reverend Canon Thomas W. Mussen: The Descent from the Cross. In recent years this print has been dismissed by a local print dealer, on unspecified grounds, as a “bad impression, not by Rembrandt.” This article contradicts the dealer’s opinion and relates McGill’s fine print (etching) to the plate from which two impressions were taken – one in the British Museum, London, the other in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Both have been directly linked to the Dutch baroque artist, Rembrandt Harmenz van Rijn, by their respective museum print experts and authenticated by the Amsterdam based committee, the Rembrandt Research Project.[1]

Impression

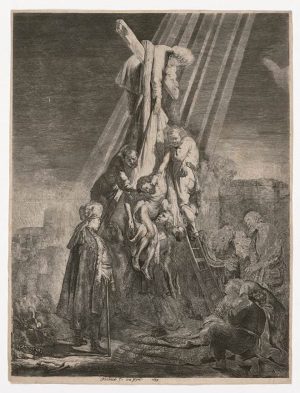

The Descent from the Cross / Etching and burin / 52.2 cm x 41 cm / Inscription: Rembrandt f. cum priyvl 1633 / Watermark to be determined by radiography

As rumor has it, potent but often false, I was told that the Rare Books and Special Collections at McGill University has a bad print, an imitation after Rembrandt, not worth mentioning. Swayed at first by rumor, visualizing a ‘fake,’ nearly undecipherable and full of ink spots printed from a botched copper plate, I did not initially insist on looking at it. However, after considering that even a bad impression from that time has research potential and historical authority, I decided to view the print.[2]

Etching by Rembrandt, The Descent from the Cross, 1633. 52.2 cm x 41 cm. McGill Print Collection, Rare Books and Special Collections, European Folio section. Click on image to enlarge.

“Excitement” is insufficient to convey the experience of seeing this large, visually demanding impression for the first time. The Descent from the Cross is a familiar composition, known from Rembrandt’s painting of the famous passion cycle, obtained by Prince Frederick Henry of Orange during the 1630s (now in Munich: Alte Pinakothek). The tableau Descent from the Cross had a particular meaning for Rembrandt. It won him the royal patronage for which most artists were striving at that time, but only few gained. This painting caught the eye of the Prince’s secretary, Constantijn Huygens, who initiated the commission for six ensuing paintings that make up the passion cycle.[3] (This information is derived from seven letters Rembrandt wrote to Huygens, the artist’s only known correspondence). To turn the painted composition into an impression was an established practice, especially of renowned works. Italian and German artists employed the graphic medium to make their works known. Engravings/etchings protected the authenticity of pictures – often copied via painting – and ensured a greater distribution, serving as advertisements for an artist’s work, especially at the beginning of a career. In the Holland of Rembrandt, prints found a new circulation terrain due to increased prosperity among the populace which resulted in an expanding art market.[4] Nadine M. Orenstein, print curator at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, who published a critical analysis of the New York ‘Descent’ in 1995, remarked “the grand scale and heavy finish of [this] etching, which stands apart of Rembrandt’s characteristically small, loosely drawn prints of the 1630s, reflects this purpose”[5] : circulation.

Lover of Art

It must have been the drama, the appeal to emotion so well expressed in The Descent, that attracted Thomas W. Mussen to the impression. Mussen was “a man of culture and erudition, and a lover of Art,” to use J. Douglas Borthwick’s words. He possessed, as Borthwick wrote, “a large collection of coins and engravings by the old Masters, also a rare collection of books. These he got by great diligence and economy.”[6]

Thomas W. Mussen (1832-1901) was born in Montreal and studied at McGill. After graduating, in 1856 he went on a grand European tour, returning in 1858.[7] His travel account, given to McGill together with the Decretia gratian, a digest of Ecclesiastical Law, records a visit to a Paris book dealer.[8] It may also have been in Paris where he obtained the Descent from the Cross. Paris, at that time, was a storehouse for Rembrandt oeuvre.[9] Whatever the case, The Descent from the Cross arrived in Montreal folded, but in superb condition. Folding the large print horizontally must have been necessary for the voyage. Surprisingly, the composition on the recto (front) does not suffer from the fold. In fact, the fold can be noticed only from the back (verso). Originally, the impression was on a thin sheet of paper, like the Metropolitan Museum ‘Descent,’ but backed by a second sheet (likely added in the late seventeenth century) in order to stabilize the work. This facilitated the fold and ultimately the journey across the Atlantic.

Identical Prints

Calling on Gary Tynski, Curator of Prints in McGill’s Department of Rare Books and Special Collections, we compared the impression to good photographic reproductions of the prints in New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art and London’s British Museum. The three prints are identical in size, composition, technique and execution – except for slight variations in ink distribution, an occurrence contingent on manual application (ink is newly applied each time a sheet of paper is to be pulled from the plate). We concluded that all three impressions must derive from the same plate. (The British Museum has another impression of “The Descent,” an earlier attempt in which Rembrandt experimented with both the composition and technique. However, the plate was unevenly bitten by the acid, and turned out not to be a success.)[10]

Seventeenth Century Paper

McGill’s impression is on seventeenth-century paper. This is the conclusion reached after examining the print together with Dr. Richard Virr, Curator of Manuscripts, McGill Rare Books and Special Collections, and after telephone-conferencing with Nadine M. Orenstein, in New York, which whom I discussed at some length the Metropolitan and McGill prints and their paper. McGill’s Descent is printed on laid paper, used during the seventeenth century when paper was still hand pressed. Laid paper shows wire marks which derive from the molds into which the cellulose mixture was placed. Interestingly, paper used at the time in Holland was most often imported from France or from the Far East and was often given Dutch watermarks.[11] Watermarks are distinct designs – grapes, fleur de lis, foolscap, coats of arms – which link paper to particular houses of production. Sometimes a watermark also indicated quality level.[12] Watermarks are usually seen when the sheet of paper is held against a strong light (the New York ‘Descent’ has a grape watermark). Dr. Virr and I looked for this distinct feature but could not discern it in McGill’s impression. Our investigation was hampered by the second sheet onto which The Descent, has been placed. However, what human eyes cannot detect, beta- or X-radiography can determine – a means currently used in the study of impressions from that period.[13]

[1]The impression is discussed in Corpus 11, closely associated with the compositional development of the Munich painting: The Descent from the Cross. J. Bruyn, B. Haak, S.H. Levie, P.J.J. Van Thiel, E. Van De Wetering in collaboration with L. Peese Binkhorts-Hoffschelte and J. Vis, A Corpus of Rembrandt Paintings 11, 1631-1634 (Dordrecht and Boston: Martinus Nijhoff Publishers), 1982, 278-287.

[2] To Nadine M. Orenstein, print curator at the Metroplitan Museum of Art, New York, I extend my thanks for enthusiastically offering me her time and expertise. Thanks are due to Dr. Richard Virr, curator of manuscripts, and Gary Tynski, print curator, both of McGill’s Department of Rare Books and Special Collections. R. Virr kindly pointed me to bibliographic sources and to McGilll’s T. W. Mussen File. My appreciation is extended also to Andrea Fitzpatrick for her editing skills. Special thanks go to Dr. Hans Möller, founder and first editor of Fontanus, who shared my enthusiasm for the print.

[3] Rembrandt painted this image on panel (like Rubens’ ‘Descent from the Cross’), although the other tableaux of the Passion cycle are painted on canvas. This may indicate that his Descent was initially conceived as an independent work. Christopher Brown, Jan Kelch & Pieter van Thiel, Rembrandt: the Master 6 his Workshop (New Haven and London: Yale University Press and National Gallery Publications), 1991,156-160 (Henceforth referred to as Brown et al).

[4] For the art market in Holland see: Svetlana Alpers, Rembrandt ‘s Enterprise. The Studio and the Market (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press), Not a bad ‘Impression’ 1988, 88 ff. and Simon Schama, The Embarrassment of Riches. An Interpretation of Dutch Culture in the Golden Age (London: Fontana Press), 1987, 290ff. and Neil de Marchi and Hans J. van Miegrot, “Art, Value and Market Practices in the Netherlands in the Seventeenth Century,” The Art Bulletin, September, 1994.

[5] Nadine M. Orenstein, “Rembrandt’s Prints and the Question of Attribution,” pp. 201-102 and catalogue entry LLThe Descent from the Cross,”pp. 228-229, both in Rembrandt/Not Rembrandt in the Metropolitan Museum of Art: Aspects of Connoisseurship, vol. II (New York: Harry N. Abrams, Distributor), 1995; and Christopher White, Rembrandt as an Etcher. A study of the artist at work (London: A Zwemmer Ltd.), 1969, vol. 2, for reproduction of prints in the British Museum pp. 22-24, and vol. 1 for text, pp. 33-36.

[6] Reverend J. Douglas Borthwick, History of the Diocese of Montreal 1850-1910 (Montreal: John Lovell & Son, Limited), 1910, 120-122. R. Virr referred me to this source.

[7] Borthwick, 120.

[8] T. W. Mussen File, Rare Books and Special Collections, McGill University.

[9] For information on art dealings see Jan Kelch, Bilder im Blickpunkt: Der Mann mat dem Goldhelm (Berlin: Gemaldegalerie), 1986, 11 ff.

[10] Orenstein, 228. For the reproduction of this plate see White, vol. 2, plate 23.

[11] For some of his smaller impressions Rembrandt turned to Japanese papers, reaching Holland from the Dutch trading post at Nagasaki through the port of Batavia in Java. It was known as Indian paper as it came through the Dutch East India company. White, 13-14.

[12] The Plantin publishing house in Antwerp, for instance was ordering paper by the watermark and size. Philip Gaskell, An Introduction to Bibliography (Winchester: Oak Knowll), 1994, 61.

[13] Orenstein. 203.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.