By: Rosalind Sweeney-McCabe, Museum Database Assistant, McGill Visual Arts Collection

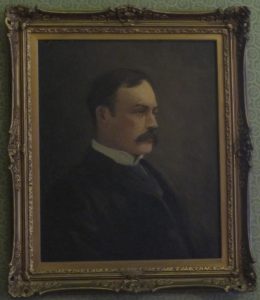

Frederick Simpson Coburn (Canadian, 1871-1960), Portrait of Dr. W. H. Drummond, 1908, oil on canvas. McGill Visual Arts Collection, 1973-07

Hanging above an armchair in McGill’s Faculty Club is a painting of William Henry Drummond (1854-1907) by Canadian artist Frederick S. Coburn (1871-1960), one of many portraits in the Visual Arts Collection on display at the Faculty Club. At first glance, the portrait appears rather ordinary. Under further inspection, however, the artwork reveals a secret, and records not one but two key figures in the life of the artist.

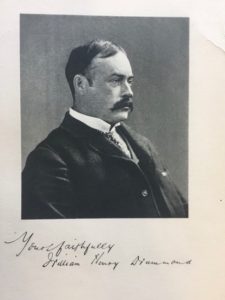

Facing you, as you sit in your chair at the Faculty Club, is, as mentioned, William H. Drummond: a celebrated medical doctor and poet in 19th century Montreal (Fig. 1). The artist had a pre-established relationship with Drummond, illustrating an 1896 book of his poetry, and several others thereafter. Coburn described Drummond as giving him his “first real confidence in” himself.[1] The portrait was painted just a few months after Drummond’s death, likely while Coburn was in London. It was drawn from a tintype photograph (Fig. 2), which, as Coburn told Drummond’s wife by letter, was the image Drummond had asked Coburn to use if he was ever to paint him.[2] There is no indication that this portrait was a direct commission. It was likely brought back to Canada from Europe by Coburn himself.

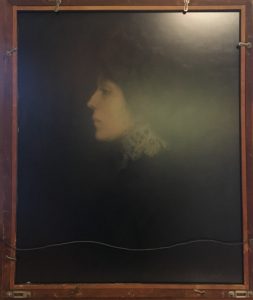

Behind the Drummond portrait, facing, for all these years, the Faculty Club wall, is a second figure (Fig. 2). Preserved within the frame under Plexiglas is a portrait of Coburn’s first wife and fellow painter, Malvina Scheepers (1896-1933). After meeting her in Belgium in 1897, Coburn kept up a long-distance correspondence with Scheepers until she came to Canada in 1915 during the First World War. The two married in 1916. Malvina was the subject of many of Coburn’s paintings, both before and after their marriage. A full body portrait of her from 1903 hangs in the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts (MMFA) down the street on Sherbrooke. Malvina was Coburn’s first love. After re-uniting in Canada, they became inseparable –companions both in life and in their artistic practices. An accomplished artist herself, Scheepers never reached the same level of success as her husband. Like many female artists at the time, she was largely relegated to muse and wife: the “woman behind the man.”

Fig. 3: Frederick Simpson Coburn (Canadian, 1871-1960), Portrait of Malvina Scheepers, N.D., oil on canvas. McGill Visual Arts Collection 1973-057.

Whatever Malvina’s age, Coburn always painted his wife in an idealized and youthful fashion. It is difficult, therefore, to guess when he painted this undated portrait specifically. Regardless of date, the two sides reflect a deeply personal history for the artist. Both figures died before Coburn; in this way, the canvas also acts as a testament to memory.

The practice of reusing surfaces is common in the history of art. In some instances, it can save artists the cost of additional supplies. Because Coburn was travelling at the time the portrait of Drummond was painted, it is very likely that he used both sides so that he could save baggage space. Salvador Dali’s Portrait of Maria Carbona (1925), displayed on the first floor of the Peace Pavilion at the MMFA is another example of a double-sided canvas. Painted during Dali’s art school days, the work is very likely the result of the artist trying to save money. Floating within a wall, glass on either side, Dali’s work is shown so that the viewer is able to appreciate both sides of the canvas: a portrait on the titular side, and a fragment of a still life on the other.

Displaying Coburn’s double-sided painting in this way would not be possible: unlike Dali’s work, both portraits share the same board and were painted in opposite orientations; one cannot be shown right-side up without the other being shown upside down. Drummond, a prominent Montrealer with strong ties to McGill, has inevitably been prioritized in the Faculty Club display. As it becomes essential for storied institutions like McGill to rethink the figures that they elevate and the histories that they tell, discoveries like these can prove helpful. Malvina Scheeper’s portrait, facing the wall for all these years, points us toward alternate histories; previously overlooked, their telling is long overdue.

[1] Coburn, Evelyn Lloyd. F.S. Coburn: Beyond the Landscape. Erin, ON: Boston Mills Press, 1996, page 41.

[2] Ibid, page 59. The tintype photograph was found on a loose page inserted into the McLennan Library’s copy of (Drummond, William Henry. Johnnie Courteau: And Other Poems. New York, NY: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1901. ). The page was signed, “Yours Faithfully, William Henry Drummond.” Because the size of loose page does not match the book’s, we are at this time unsure of its provenance or if the inscription is original.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.