What does Emancipation Day have to do with the Osler Library? Superficially, not much. Peel back the layers of the history of medicine, though, and the relevance becomes clear. For centuries, medicine has been used to generate and perpetuate ideas about race that we now know to be false. In the health professions, racist ideologies have been linked to poor health outcomes.

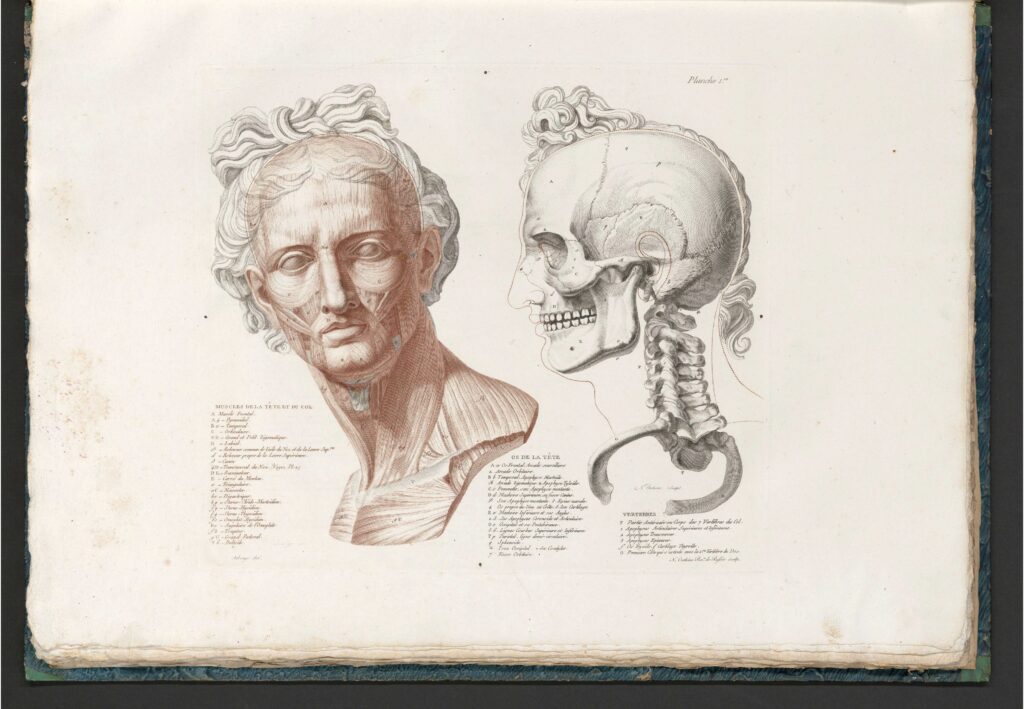

Sometimes race appears in unexpected places. In his 1812 work, Anatomie du gladiateur combattant, applicable aux beaux arts, Jean-Galbert Salvage looked to the Bible as history to explain the origins of the three human races he identified within his work: White, Black, and Asian. His specific concern was to use the medical expertise he gained as a student in Montpellier to teach artists about the primary characteristics of men of different races (and, within Europe, different countries) to help his peers create accurate portraits as well as historical compositions. [p.56]

In introducing the “white race,” he describes the brain as being “larger than the bones of the face,” [56] implicitly but without subtlety setting up the impression of intellectual superiority. Between the “white races” he further examines the characteristics of those who inhabit different regions of Europe. He ties his explanations to humoral theory and links regional environmental characteristics to the people who inhabit them: thus, those living in the “temperate regions” of Greece, Italy, and France were “more temperate, with all the purity of design and the right proportions.” That Salvage’s descriptions of human races are highly subjective – even if masquerading behind medical authority – is clear from his comparison of different Europeans.

In observations that undermine any sense of medical objectivity, Salvage uses his understanding of humoralism and human characteristics to place the French above the English: “The French have always had a sanguine, cheerful, light and playful complexion: the open physiognomy…of elegance and vanity distinguishes them from other peoples….” [p.56] By comparison, “In the English, the complexion is more bilious, the features are more pronounced, the head and the face are broad… they show pride and obstinacy in their character… Although many of them are blond and redheaded, they often have a livid and atrabilary shade in their complexion….” Among other Europeans, Italians have a “habitual penchant for pantomime, gesticulation of all parts of the body”; Germans are identifiable by their “lymphatic temperament, constancy, severity, their height and sturdy limbs.” [p.56]

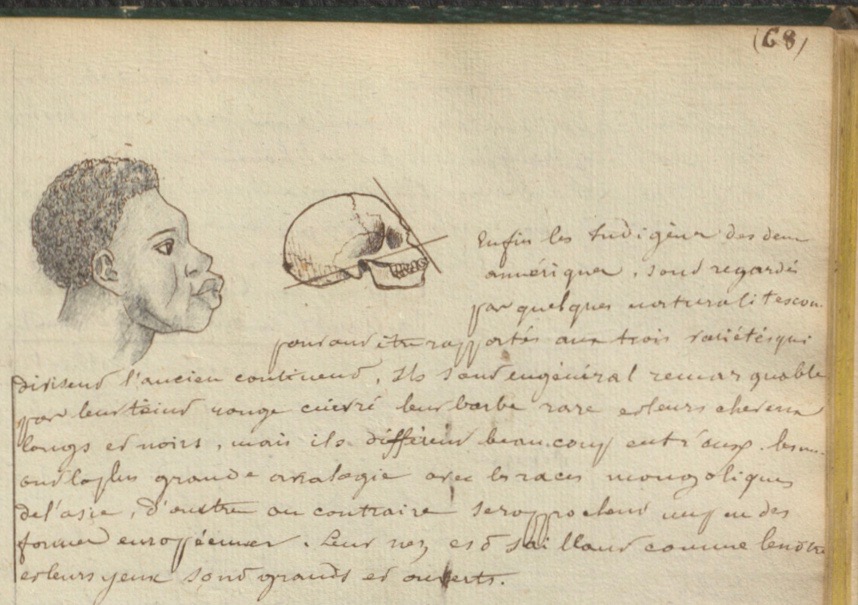

Within the same work, the attention given to non-Europeans was considerably less extensive, reinforcing their diminution: Salvage devoted just over one page to whites versus just over half a page combined to discuss Blacks and Asians (including North American “savages” with the latter group).

The most drastic dehumanization is reserved for those who are Black. Salvage reinforces these views by describing “la race ou espèce nègre,” suggesting that Blacks are not just a different race, but might be regarded as a different species altogether. The description leaves little question about Salvage’s feeling on the subject, as he compares Black hair to sheep wool and further diminishes Black humanity by proposing a negative correlation between genital size and intellect. Though he makes only passing references to slavery, his descriptions make it clear that he accepts and takes for granted the enslavement of Black peoples. [p.57] Moreover, though Salvage describes Blacks as greedy and lecherous, he does not discuss temperament in the way he does with other races. By omission, he removes what would have been regarded as a central human characteristic and thus confirms his dehumanization of them.

Salvage presented himself as an authority who had studied medicine, as one who could convey his deep understanding of the human form to artists in order to improve the accuracy of their depictions. In other words, what we regard as highly racialized and racist descriptions, he presented as the teachings of a man of intellect and authority.

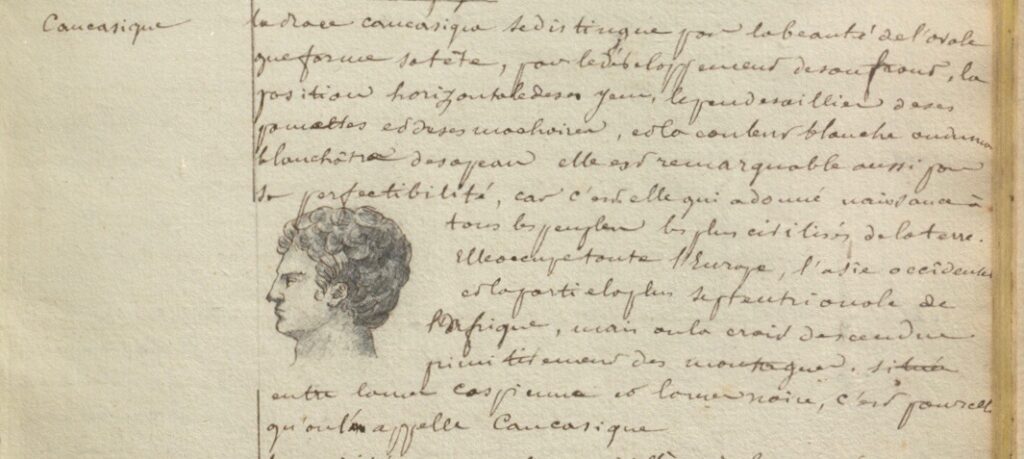

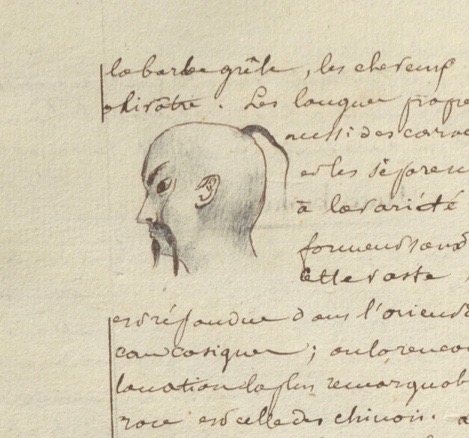

Two decades later, also in France, Eugène Ducrot casually included similar beliefs about non-European races, presenting stereotypes as facts to be absorbed. In his Cahier d’histoire naturelle of 1835-37, Ducrot copied details from the lectures he attended at the university in Moulins. Like Salvage, he describes three races: Caucasian, Asian, and African (Causiatique, Mongolique, Ethiopique). He begins by remarking upon the physical beauty of Caucasians, noting their “perfectability.” [p.66] His descriptions are mainly of superficial physical characteristics, which he renders into sketches within his notes.

In the works of both Salvage and Ducrot, the ideal form is one we would recognize in an ancient Greek statue. This leads to the question: when these beliefs are legitimized in works by medical professionals and in university teaching, what is the impact upon the attitudes of those responsible for the care of others? The sketches Ducrot made in 1835-37 appear as caricatures to the viewer in 2020; in other words, in student notes of the nineteenth century we can see the roots of racist attitudes that for generations were casually taken in as facts.

While the clear prejudice present in the above examples is at a level that we can easily call out as damaging, it is worth considering the harm done by omission. Medical texts printed in Europe and North America have historically presumed a northern European male subject. Women appear on occasion, and usually with reference to medicine that was connected in some way to the female reproductive system. Looking forward to a future blog post, it is worth examining the detrimental impact of omission on medical outcomes.

References

Eugène Ducrot, Cahier d’histoire naturelle (1835-1837). Manuscript, Osler Library of the History of Medicine. https://archive.org/details/McGillLibrary-osl_cahier-dhistoire-naturelle_QH51D831837-18271.

Jean-Galbert Salvage, Anatomie du gladiateur combattant, applicable aux beaux arts (Paris, 1812). https://archive.org/details/McGillLibrary-osl_anatomie-gladiateur_elfNCS182a1812-17719.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.