Dr. Jessica Stacey is a recipient of the 2019 Raymond Klibansky Collection Research Travel Grant, awarded to pursue research with McGill’s Voltaire Collection.

J. Patrick Lee Voltaire Collection

At the McGill Library last autumn, I was putting the finishing touches on a foreword to the manuscript of my book (working title Authors of Catastrophe: narrative and historicity in eighteenth-century France). I knew that the Foreword would almost certainly have to change as the book moved through the final cycles towards publication, but I had been struck by the pertinence of my experiences in Montreal to the book’s subject, which is the use and reuse of catastrophe narratives to delineate the situation of a given community within — or sometimes outwith — its epoch. After witnessing the reception of Greta Thunberg at Montreal’s largest ever rally on Friday September 27th, I realised that she had rocketed from a public figure still able to turn up to a relatively small crowd, as when she attended the Extinction Rebellion occupation of central London that spring, to the protagonist of a swirling set of narratives — friendly and unfriendly! — around the climate movement. In a reflective mood, I wrote:

‘The third decade of the twenty first century seems to be dawning as period of crisis in many political and environmental contexts. But then, we live in permanent crisis, now, so much so that it sometimes seems that our best hope is to prolong our state of crisis indefinitely, postponing its resolution into catastrophe. 2019 saw waves of climate action from Extinction Rebellion and other groups, whilst Greta Thunberg’s speech at the United Nations Congress saw her transformed, in the media narrative and no doubt for many spectators, almost overnight from a prominent activist into a full-blown star, even a hero.’

Now, back in London and deep into the Covid-19 pandemic, I am preparing the very final version of the manuscript, and I’m stuck on what to do with this Foreword. Even this brief evocation of what was the writing context looks naive and out of date in the wake of yet more overnight transformations, revelations and peaking crises.

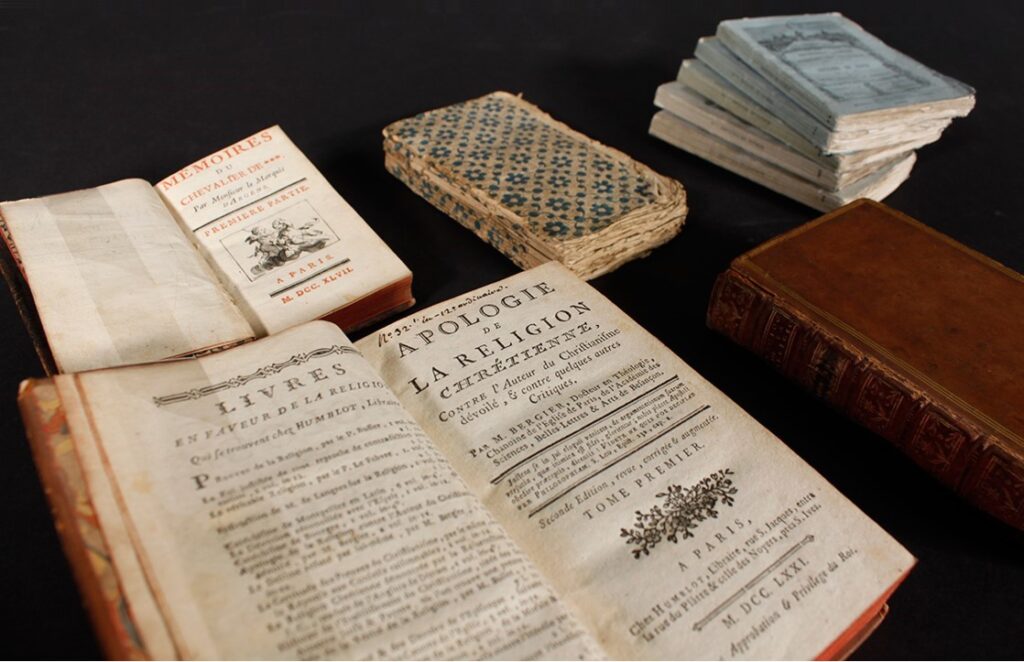

Like many, I am now working through a barrage of distractions, and listening to the buzz of our neighbours’ power tools I am nostalgic for the hush of the McGill Rare Books Reading Room. As well as revising the book manuscript, I was accessing the J. Patrick Lee Collection for a project on how metaphors of the life-cycle of iron, from mining to rusting, were used to express ideas around the rise and decline of civilisations in philosophe and anti-philosophe writing.

Voltaire, whose works and reception are strongly represented in the collection, was a great fan of metaphorising barbarism as rust. I was particularly interested in seeing whether this imagery was picked up in translations and compilations of Voltaire’s work, but one of the most interesting things I came across was in a work deeply hostile to Voltaire. In Voltaire parmi les ombres (1776), the author Charles-Louis Richard rather cruelly imagines a deceased Voltaire (only two years before the aged author actually did die) confronted and confounded in the afterlife by those he had admired, as well as by those he had derided.

Challenged by the spectre of Bossuet, Voltaire is accused in the following terms: ‘sous le spécieux prétexte d’analyser les faits, vous les avez réellement altérés ou changés; vous les mettez confusément dans le creuset Philosophique; & par une sorte de chymie illusoire, vous n’en tirez que le mensonge.’ [under the specious pretext of analysing things, you really altered or changed them; you threw them confusedly into the philosophic crucible, and through a kind of illusory chemistry, you extracted only lies.]

This accusation anticipates the post-Revolutionary rhetoric of Antoine Rivarol, who would also write of the philosophes as maleficent chemists, putting the nation into their crucible, breaking down the shiny surface maintained by the enamel of religion, tradition and respect for one’s betters to reveal the rusty barbarism within (Rivarol displays here an understanding of rust based in the outmoded phlogiston theory, according to which rust is internal to iron — a terre contained by an unstable union with the phlogiston which is ever prone to escape). I am now considering how this project may lead into a more ambitious work that would treat the political uses of technical metaphors over time, testing Hans Blumenberg’s claim from Paradigms for a Metaphorology that ‘organic “images” of society are propagated by conservative theorists or lead to such theories, [whilst] mechanical social metaphors predispose to revolution.’ Simply fact-checking this sweeping claim would be of limited interest, but I am intrigued by what happens where the boundary between the natural and the technical or mechanical is blurred — iron has a foot in both camps — and by what looking at a time prior to the fixing of this distinction can bring to the table. Under the sway of human-caused climate change, can one even distinguish cleanly between natural and mechanical or technical metaphors any more? Does the all-encompassing theory of the network (planetary, neural, digital) steer us towards a particular politics?

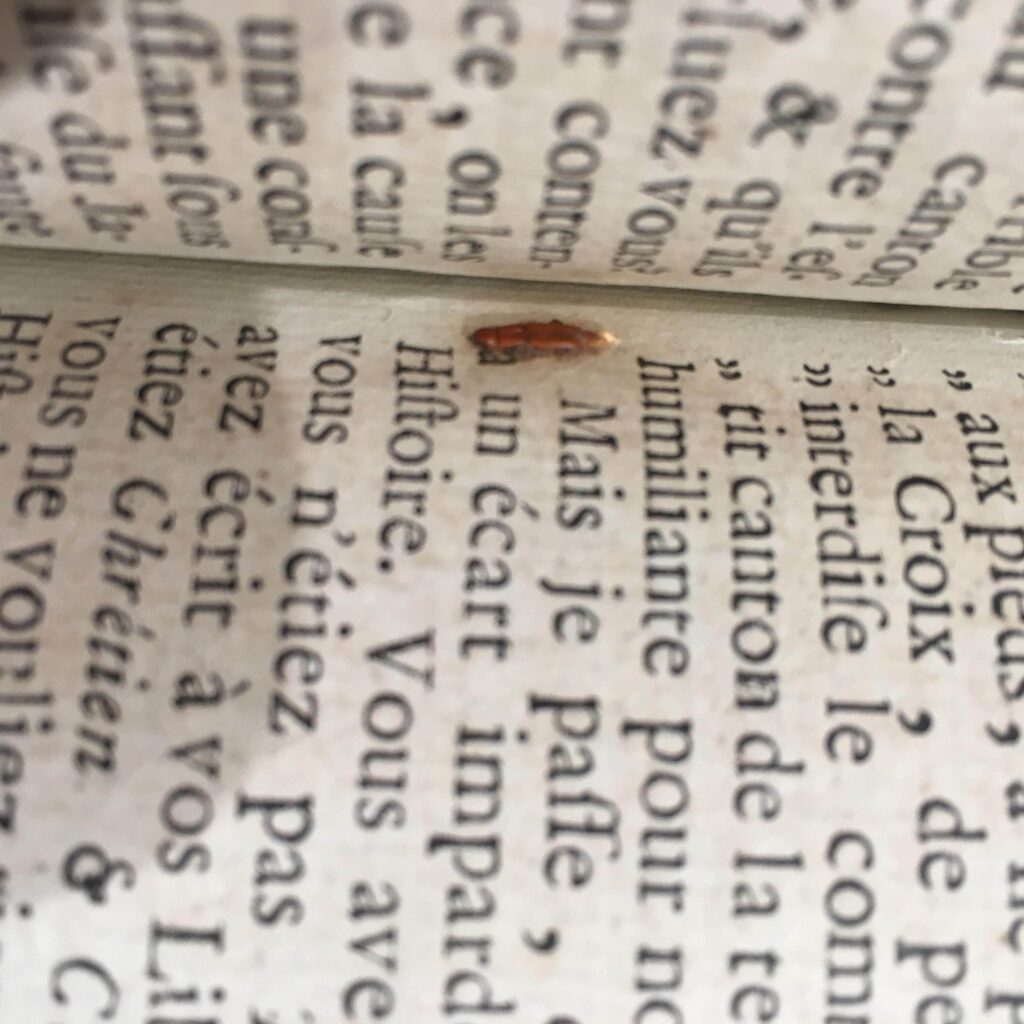

In addition to my nostalgia for the peace of the library, I miss the possibility for unexpected encounters — less likely when one is researching online with searchable texts (which are of course very useful indeed). I include a slightly blurred image of one such encounter: a real bookworm! The photo below shows its path through the book to its final resting place. I must add that this is a historic pest; the curator of the collections assures me that the environment in which the books now live is free of infection!

Lastly, I wish to express my thanks to all the wonderful library staff who assisted me during my visit, to the librarians for inviting me, and particularly to Ann Marie Holland, curator of the Enlightenment Collections, for her support and camaraderie.

By Dr. Jessica Stacey. You can read more about the Raymond Klibansky Collection Research Travel Grant, and Dr. Stacey, here.

For more information on McGill’s Voltaire Collection and the J. Patrick Lee private library purchase, please click here.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.