By Melody Hsu, McGill Visual Arts Collection Museum Database Assistant (2022), B.A Art History and International Development, Minor Communications, 2022

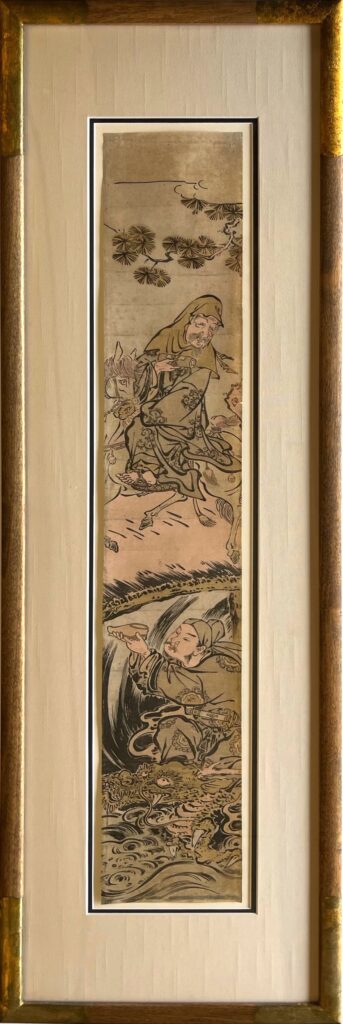

A smirking, elderly man atop a galloping horse gazes down at a young man kneeling on a dragon. The young man politely offers a shoe to the older man, who has a bare left foot. Reading from the top to the bottom, this 92.5 x 29 cm colored Japanese woodblock pillar print, hashira-e 柱絵, dated from the late 1700’s Edo Period visually narrates the famous Chinese-Han story of Choryo (in Chinese Zhangliang 張良) and Kosekiko (in Chinese Huangshigong 黄石公). The aged man can be identified as Kosekiko by his sage appearance, his hand scroll, and his lost shoe. The young man can be identified as Choryo through his scholarly clothing, his courteous obedience, and his accompanying dragon, which symbolizes his power and nobility. The McGill Visual Arts Collection’s pillar print, Two Chinese Sages Choryo and Kosekiko, depicts the historical and legendary scene of Choryo and Kosekiko that entails the valuable power of learning, forbearance, and time.

Born to a noble family, Choryo (?–186BC) was the direct male descendant of the first and second chancellor of the ancient Han state 韓國during the Warring States period. In 230 BC, the Qin state 秦國under the leadership of King Ying Zheng 嬴政conquered the Han state – and all neighboring Chinese states of Zhao, Yan, Wei, Chu, and Qi – and established the Qin dynasty 秦朝, which became the first Chinese imperial dynasty and sovereign power that unified the land of China as one nation. The Qin’s invasion of Han angered Choryo, he lost his home kingdom and his aristocratic position at the Han court. In this dire situation, Choryo used his entire family fortune and power to launch a series of planned assassinations against the King of Qin. Choryo’s attempts to kill King Ying Zheng – also known as Qin Shi Huang 秦始皇 (‘First Emperor of Qin’) – were unsuccessful. Instead, Choryo became a bankrupted nobleman and a wanted fugitive. He used fake identities to hide from the Qin authorities. Choryo eventually fled to Xiapi 下邳, an ancient city located in the northern part of the coastal province of modern Jiangsu 江蘇.

One day, Choryo saw an old man wearing a coarse fabric robe on the Yishui Bridge. Without any greetings, the old man walked towards Choryo, purposely threw his shoe under the bridge, and insolently ordered Choryo to go fetch his lost shoe for him. Astounded and offended, Choryo unwillingly went to pick up the old man’s shoe out of courtesy. On his return, the old man arrogantly lifted his bare foot and requested Choryo to put on his shoe for him. Stunned and angered, Choryo managed to remain calm, went down on one knee, and patiently put the shoe on the old man’s foot. Without any expression of gratitude, the old man turned his back and walked away with a smile. Dazed, Choryo remained in silence on the bridge until the old man returned, demanded Choryo to come back to the bridge in five days at dawn, and said: “This child can be taught!” (it is a Chinese idiom 孺子可教 that signifies one is promising and worthy to be taught). Confused with the old man’s words and actions, Choryo kneeled with respect and agreed to the old man’s demands.

When the fifth day arrived, Choryo rushed to the bridge at sun rise. Yet, the old man was already waiting on the bridge. He criticized Choryo by angrily saying: “How can you make an old man wait for a rendezvous? Come back again in five days!” After five days, the old man was again one step ahead of Choryo and demanded him to come back one more time in five days. After another five days, Choryo arrived at the bridge in the middle of the night and waited for the old man until the sunrise. This time, Choryo finally accomplished the old man’s request, he successfully arrived at the bridge at dawn before the old man. Impressed by Choryo’s sincerity and forbearance, the old man gifted him a book – a scroll – and said: “One who reads this book can become the teacher of the King. In ten years, the world will be in chaos. You can use this book to build and prosper a country. In thirteen years, I am the yellow rock resting at the bottom of Mount Gusheng”. Thereafter, the old man walked away and disappeared.

The scroll that the old man handed to Choryo was The Art of War of Taigong 太公兵法, an important ancient manuscript that expressed the essence of traditional Chinese military principles. Choryo carefully studied the book and learned its civil and military strategies. He eventually raised a grand army, secured a great number of anti-Qin allies, and fought against the Qin Empire with Liu Bang 劉邦, an ancient civil officer of the Qin court who raised to power as an anti-Qin leader soon after the death of Qin Shi Huang. With the knowledge, advice, and support of Choryo, Liu Bang successfully overthrew the Qin Dynasty and became the First Emperor of the Han Dynasty 漢朝 – Emperor Gaozu of Han 漢高祖. As a scholar highly trusted by the First Emperor of Han, Choryo still remembered the old man he met thirteen years ago on the Yishui Bridge in Xiapi and went to the bottom of Mount Gusheng as the old man once told him. There was indeed a yellow rock there. With gratitude and respect to the old man, Choryo built a shrine to worship him – the Yellow Rock Old Man (Kosekiko黃石公).

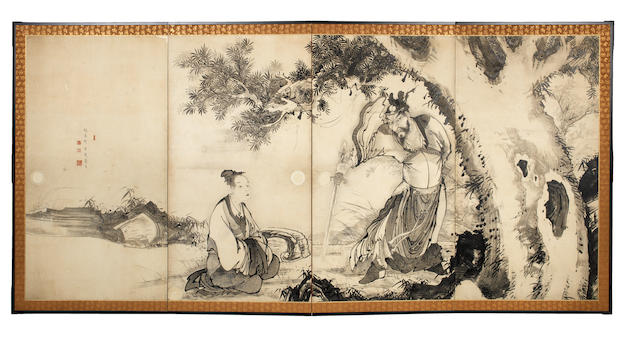

The Art of War of Taigong, the book that Kosekiko gifted to Choryo, eventually reached to the neighboring kingdom of Japan and studied by local Japanese officials and scholars as a valuable source of military, governance, and moral philosophies. From the ancient period until today, the story of Choryo and Kosekiko has been referenced in various art forms. It has been carved on late 18th-Century Japanese Tsuba 鐔 (a round safety guard placed on the grip of a Japanese sword), painted with ink on the early 19th-century fusuma 襖 (sliding paper doors), and referred to in modern Chinese pop culture’s TV shows, such as Heroes 說英雄誰是英雄 (2022). We may ask, why is the story of Choryo and Kosekiko is often represented in popular culture across different periods, places, and formats? Perhaps, the answer to this question is that the morals of this story that are rooted in ancient Chinese cultural traditions, beliefs, and knowledge have a lasting impression on East Asian societies from the past to the present. Beyond Choryo’s mastery of ancient Chinese civil and military philosophies, his journey can also teach us the important lessons in humility and perseverance. If Choryo didn’t stay patient, respectful, and loyal toward the old man and his teaching, perhaps the outcomes of Choryo’s fugitive life and hatred towards the Qin would be different. Let’s continue to reflect together on what we can learn from the story of Choryo and Kosekiko!

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.