By Serene Mitchell, McGill Visual Arts Collection Museum Database Assistant (2022), B.A History, 2022

As a student of Asian North American history, I’ve always been drawn to the development of cultural identity and understanding migration history through sites of artistic production. When I started as an intern at the McGill Visual Arts Collection, I was immediately curious about what Asian North American art was available. Determining which artworks in the collection are by artists who identify as such remains a challenge because the current catalog database records prioritize the artist’s place of birth, rather than their nationality. This is because verifying an artist’s nationality requires careful research. So, I eagerly took on the task and was able in pinpoint some remarkable pieces.

Historically, the canon of Western art history classified aesthetics, art movements, and sources informed by other cultures within the North America context as, simply, “Canadian” or “American”. For this reason, I was compelled to honour some of these artists and critically explore the ways that Asian migration has affected international art trends both historically and contemporarily. In this blog post, I introduce three examples of Asian North American art within the Visual Arts Collection. The highlighted artists are Elizabeth Quan, Tin-Yum Lau, and Ushio Shinohara. These artists and their artworks uncover intersections between Asian migration and Western art, offering an avenue to further understand the art styles that link aesthetics in North American to traditional and contemporary art in Asia. I hope this introduction to their artworks provides inroads for future researchers and helps initiate more research into other Asian North American artists represented in the Visual Arts Collection.

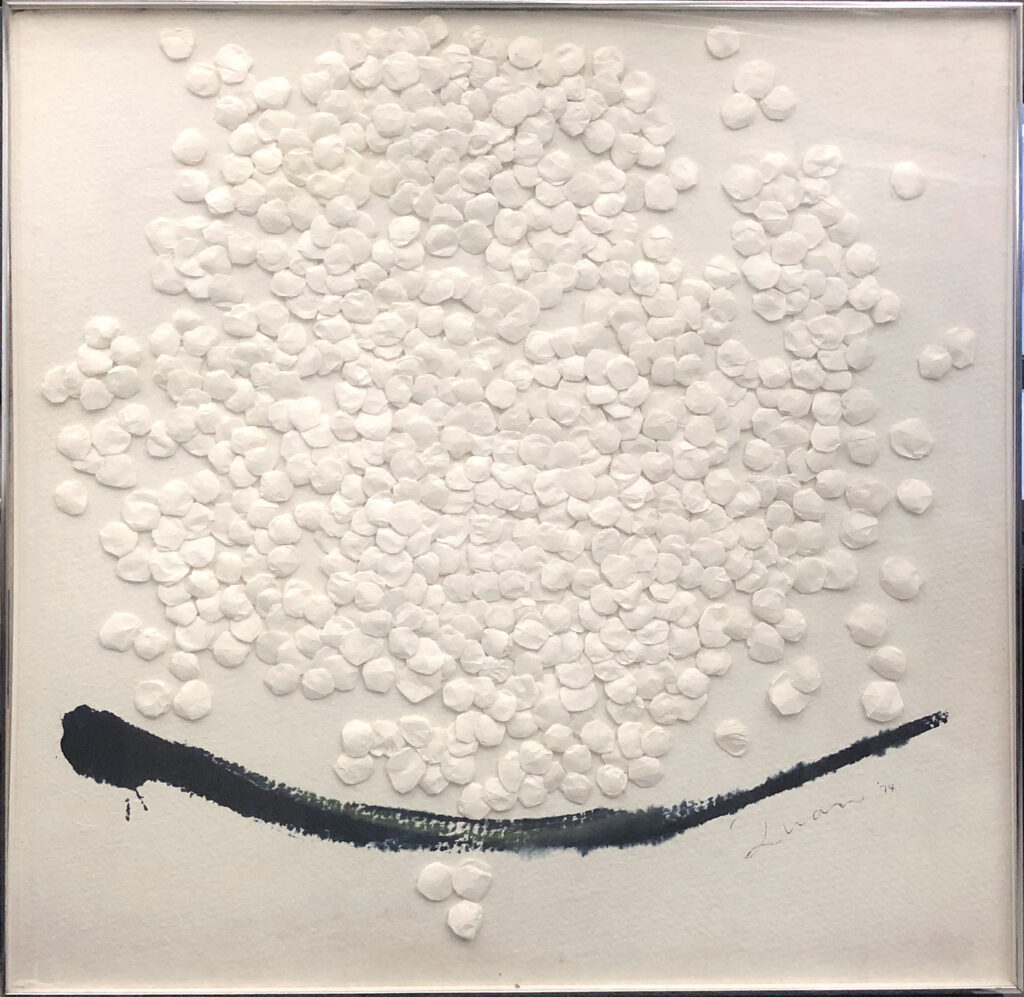

Elizabeth Quan

Asian North American artists have the capability to scramble and re-situate modern and postmodern art aesthetics by revealing to the observant viewer the ways that North American art has become the pupil to techniques and philosophies that have long been familiar in Asia. An incredible example of this is work by Chinese Canadian watercolourist, Elizabeth Quan (1921-2016). Daughter of Chinese immigrant restaurant owners, Quan grew up in in Burlington, Ontario, and began her art career in Toronto, gaining recognition after becoming the last protege of Canadian artist, Jack Pollock. Quan took East Asian studies, drawing, and painting at the University of Toronto.

In her autobiography, Quan recalls the moment she began to practice and incorporate Chinese painting techniques in her work, declaring that “it was an exciting moment, [and] the end of a long search”.[1] Winter Joy (1974) by Quan, in the VAC collection, combines innovative paper folding technique and simple gestural brush strokes. Winter Joy stunningly captures Quan’s fascination with the physical qualities of paper and the natural elements of Canada through East Asian aesthetics. The small, folded paper masses are irregularly scattered across the natural paper background, carried by a single azurite blue-green brushstroke. The large areas of empty space honour the texture of the natural paper and is all white except for the single rapid brushstroke mimicking Xieyi, a traditional Chinese painting technique that is looser in style and features exaggerated forms. The restricted colour range and aggressive and bleeding brush stroke technique used in Winter Joy could easily be attributed to abstract expressionism in America. Quan, however, cites the use of Chinese mineral-based colours and watercolour techniques for the simplicity and free movement in her practice. While artists like Jackson Pollock and Mark Rothko are often given credit for developing similar gestural and unconventional techniques, Quan’s work asserts the legacy of East Asian art aesthetics within these well-known art movements.

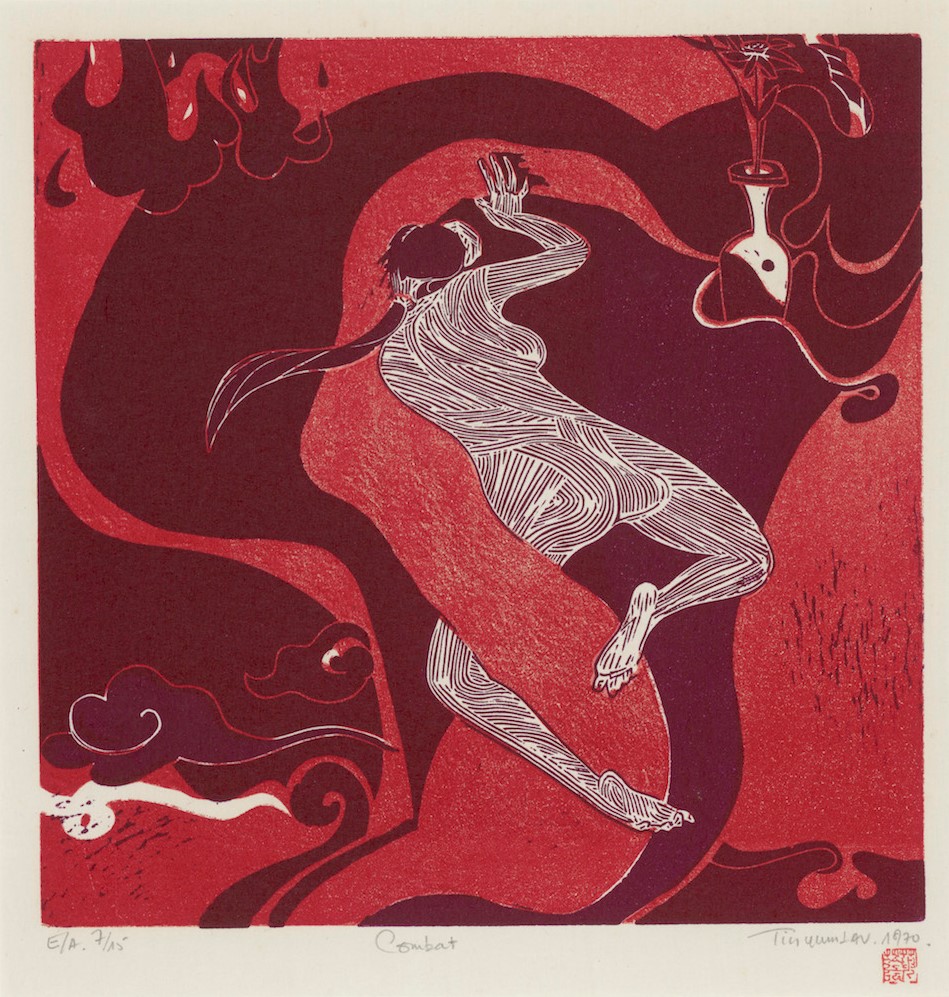

Tin-Yum Lau

The work of Cantonese-Quebecois multidisciplinary artist, Tin-yum Lau (1941-), also points to a contact between East Asian artistic methods re-invented to marry and re-imagine “Western” art. Lau is the son of a renowned calligraphist in Hong Kong, known for incorporated Chinese painting principles such as asymmetrical compositions and atmospheric fields of colour in their art. Studying Western art at the Hong Kong institute of Fine Arts, followed by the National School of Fine Arts in Paris, Lau eventually moved and settled in Montreal in 1969. In 1979, Lau was a founding member of the Conseil de la gravure du Québec, representing and disseminating the work of Québécois print makers. Lau’s red monochrome lino-cut print, Combat (1970), in the VAC collection, demonstrates the artist’s capability to create powerful images through the combination of abstract lines and Chinese symbolism. A struggling woman is depicted alone, enveloped in deep burgundy shadows, and contrasting bright red abstract shapes. Lau uses thin lines resembling the texture in muscle tissue to depict movement within the women’s body, demonstrating his technical printmaking skills.

Combat represents recurring themes Lau’s artistic practice which explores the conflict between body and soul, and the metaphysical interplay between forms in reality and dreams.[2] Each corner of the composition possesses a different image, presenting possible (dis)connections with reality, including natural elements like fire and water. The cloud in the lower left corner, depicted in a traditional East Asian style, is a motif commonly understood in East Asian cultures as an omen of good luck. The symbol of good luck both challenges and grounds the striking image of the struggling woman. Lau’s use of his Chinese seal as a signature asserts his cultural background to viewers that may not be as familiar with the subtle Chinese symbolism within the print. The imagery in Lau’s Combat speaks directly to an audience who understands the deeper meanings of these East Asian symbols, while giving viewers with no prior knowledge hints of where to dig deeper.

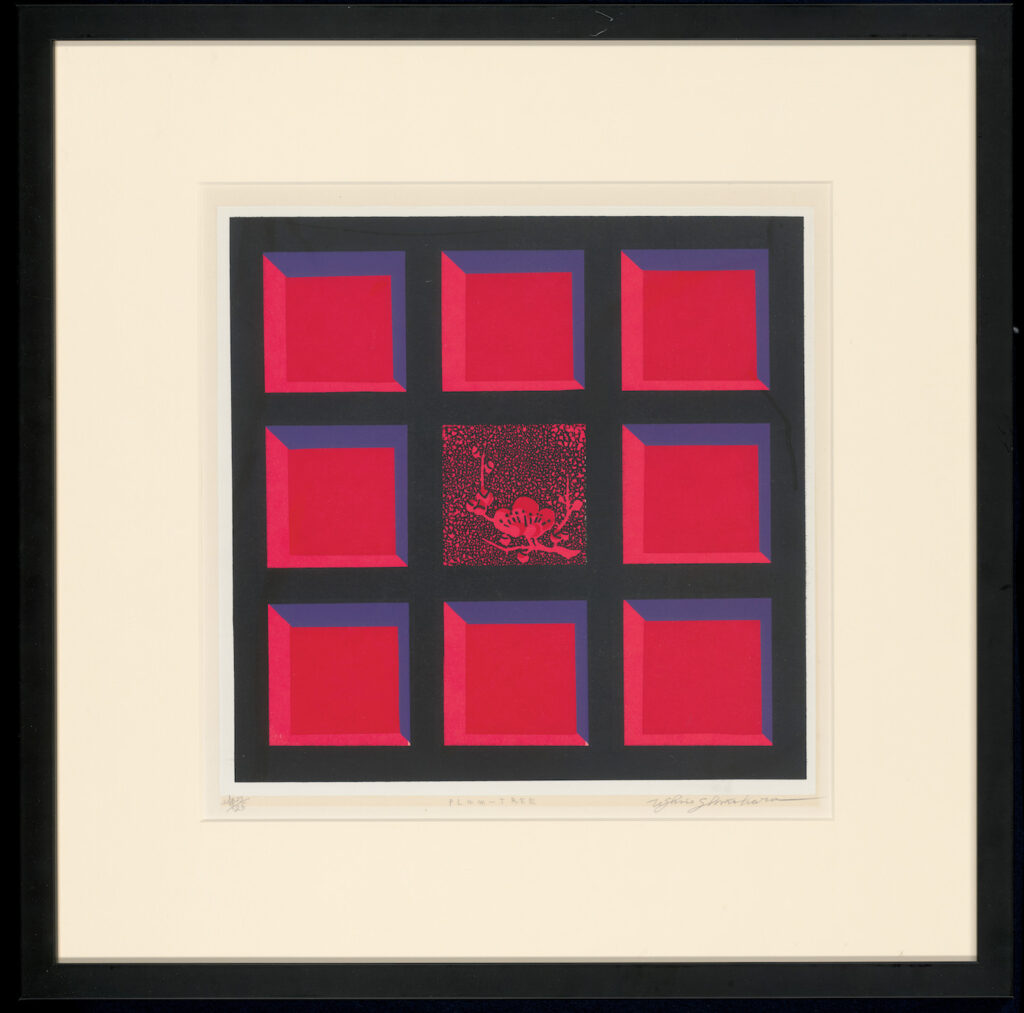

Ushio Shinohara

Lastly, I would like to introduce Ushio Shinohara’s screen print, Plum Tree. Shinohara (1932-), well known for being the subject in Zachary Heinzerling’s documentary Cutie and the Boxer (2013), is a Japanese Neo-Dadaist from Tokyo who moved to New York in 1969. A child of two artists, Shinohara studied painting at the Tokyo Art University in 1952. Shinohara never finished his degree and was drawn to “anti-art” early in career, eventually joining Japanese Neo-Dada collectives. It was within this art movement that Shinohara began to use his body as the medium of his art, leading what the groups would later term “creative destruction”.[3] In June 1960, at the height of anti-US Japanese Security Agreement protests Shinohara’s Neo-Dadaist Collective was highly involved in, Shinohara first performed his now-famous “boxing painting”, punching a large piece of paper with boxing gloves that were dipped in paint.

Plum Tree was most likely done by Shinohara in the same period he created his successful series of prints, Oira. This series depicted Oiran, highly ranked courtesans of the Japanese Edo period (1600-1866). Contrasting the traditional depictions of Orian’s natural beauty, Shinohara depicts Orian unattractively with fluorescent paint inspired by pop art. Plum Tree is composed by a minimal black square grid with three rows and three columns. All but the center square is coloured in with a Munsell red, with a dark periwinkle depicts a width and upper face, giving the squares a three-dimensional appearance, complicated by a bright pink mirroring width on the left side and lower face. Shinohara’s use of bright and contrasting colours mimics the use of art pop style in Oira. The middle square is occupied with a simple plum blossom, a symbol of hope and renewal in Japanese culture. The plum blossom is presented against a speckled background with the black and the bright pink used in the other squares. Like Lau, Shinohara inserts East Asian symbolism into his work as a subtle hint to the potential meaning behind his practices.

Asian North American art is transnational and transcultural in character, forged in relation to power, always transforming and reinventing itself. “Asia” has been and continues to be a place of imperial imaginings created within European and Western colonial desires and fears. For these reasons, Asian North American art requires on-going critical intervention to prevent reductionist classifications. This introduction to three artworks is just the beginning of work that could be done at the VAC. I encourage other Asian and Asian North American students and researchers to use these artistic productions as sites of recognition and resistance that challenge the orientalist and primitivist assumptions within Western frameworks. Asian North American art, by nature of its diversity, works against overarching Western approaches that essentialize Asian art, taking a radical stance that re-invents and restructures both epistemologies. At times disjointed, while other times speaking in dialogue, Asian North American art and practices hold a variety of migration stories and traditions missing in art histories.

[1] Elizabeth Quan, My Life –My Art (Toronto: Sounds Canada Publishing, 1999), 80.

[2] Tin-Yum Lau, Body and Soul (Montreal: Trigram, 1996), 2.

[3] Paul Schimmel, Kristine Stiles, and Museum of Contemporary Art, Out of Actions: Between Performance and the Object, 1949-1979 (Los Angeles: Museum of Contemporary Art, 1998), 26.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.