By Eden Autmezguine, 2nd year student, Faculty of Arts and Science and Student Project Assistant in Rare Books and Special Collections. Eden’s position is made possible thanks to funding from the SSMU Library Improvement Fund.

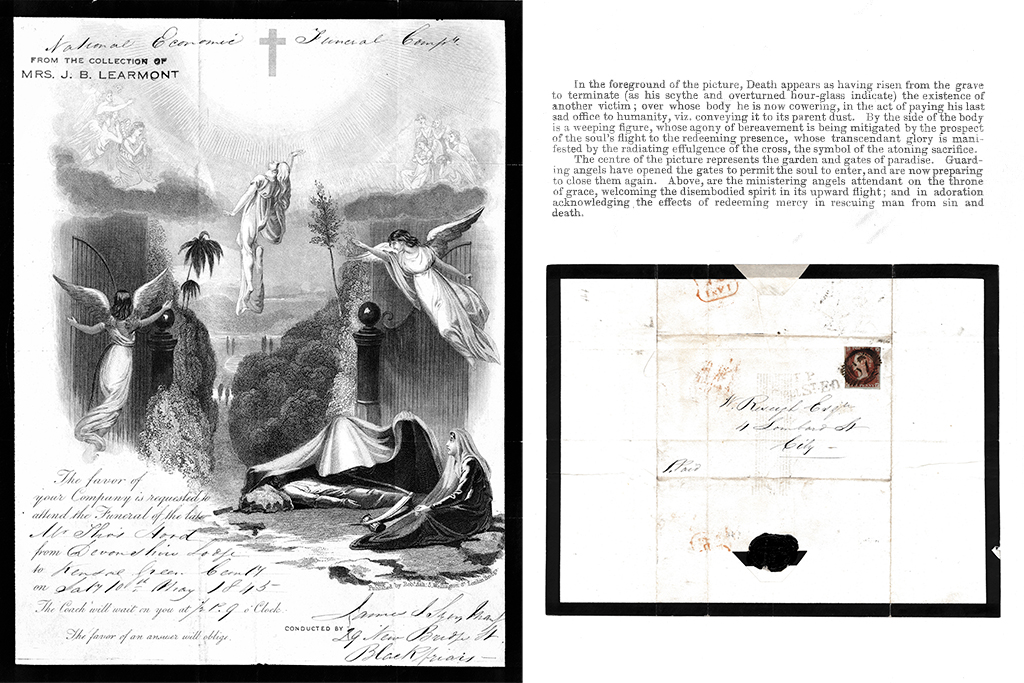

Pictured above from the holdings of McGill’s Rare Books and Special Collections is an extravagant Victorian-era funeral notice on black-bordered mourning stationary for Mr. Thomas Hood, with a detailed illustration on the front and an accompanying caption inside which reads:

“In the foreground, Death appears as having risen from the grave to terminate (as his scythe and his overturned hour-glass indicate) the existence of another victim; over whose body he is now cowering, in the act of paying his last sad office to humanity, viz. conveying it to its parent dust. By the side of the body is a weeping figure, whose agony of bereavement is being mitigated by the prospect of the soul’s flight to the redeeming presence, whose trancendant [sic] glory is manifested by the radiating effulgence of the cross, the symbol of the atoning sacrifice.

The centre of the picture represents the garden and fates of paradise. Guarding angels have opened the fates to permit the soul to enter, and are now preparing to close them again. Above are the ministering angels attendant on the throne of grace, welcoming the disembodied spirit in its upward flight; and in adoration acknowledging the effects of redeeming mercy in rescuing man from sin and death.”

Thomas Hood, born 23 May 1799 and deceased 3 May 1845 at the age of 45, was an English poet, author and humorist. He was a regular contributor to the London Magazine, Athenaeum, and Punch, and later on in his life started a magazine founded in his own name. He married Jane Reynolds. Their first child, a daughter, died at birth, but they later had another daughter, Frances Freeling Broderip, and a son, Tom Hood. Both children followed in their father’s footsteps, with Frances becoming a children’s writer and Tom a humorist and playwright.

Hood’s best-known work in his lifetime was “The Song of the Shirt”, a poem written in honour of a Mrs. Biddell, a widow and seamstress who, in a desperate attempt to feed her starving infants, pawned the clothing she had made in the service of her employer. The poem was published anonymously in the Christmas edition of Punch in 1843 and quickly became a public sensation, inspiring social activists who actively opposed the oppressive conditions of England’s working poor. Read the full poem below.

The Song of the Shirt by Thomas Hood

With fingers weary and worn,

With eyelids heavy and red,

A woman sat in unwomanly rags,

Plying her needle and thread—

Stitch! stitch! stitch!

In poverty, hunger, and dirt,

And still with a voice of dolorous pitch

She sang the “Song of the Shirt.”

“Work! work! work!

While the cock is crowing aloof!

And work—work—work,

Till the stars shine through the roof!

It’s O! to be a slave

Along with the barbarous Turk,

Where woman has never a soul to save,

If this is Christian work!

“Work—work—work,

Till the brain begins to swim;

Work—work—work,

Till the eyes are heavy and dim!

Seam, and gusset, and band,

Band, and gusset, and seam,

Till over the buttons I fall asleep,

And sew them on in a dream!

“O, men, with sisters dear!

O, men, with mothers and wives!

It is not linen you’re wearing out,

But human creatures’ lives!

Stitch—stitch—stitch,

In poverty, hunger and dirt,

Sewing at once, with a double thread,

A Shroud as well as a Shirt.

“But why do I talk of death?

That phantom of grisly bone,

I hardly fear his terrible shape,

It seems so like my own—

It seems so like my own,

Because of the fasts I keep;

Oh, God! that bread should be so dear.

And flesh and blood so cheap!

“Work—work—work!

My labour never flags;

And what are its wages? A bed of straw,

A crust of bread—and rags.

That shattered roof—this naked floor—

A table—a broken chair—

And a wall so blank, my shadow I thank

For sometimes falling there!

“Work—work—work!

From weary chime to chime,

Work—work—work,

As prisoners work for crime!

Band, and gusset, and seam,

Seam, and gusset, and band,

Till the heart is sick, and the brain benumbed,

As well as the weary hand.

“Work—work—work,

In the dull December light,

And work—work—work,

When the weather is warm and bright—

While underneath the eaves

The brooding swallows cling

As if to show me their sunny backs

And twit me with the spring.

“O! but to breathe the breath

Of the cowslip and primrose sweet—

With the sky above my head,

And the grass beneath my feet;

For only one short hour

To feel as I used to feel,

Before I knew the woes of want

And the walk that costs a meal!

“O! but for one short hour!

A respite however brief!

No blessed leisure for Love or hope,

But only time for grief!

A little weeping would ease my heart,

But in their briny bed

My tears must stop, for every drop

Hinders needle and thread!”

With fingers weary and worn,

With eyelids heavy and red,

A woman sat in unwomanly rags,

Plying her needle and thread—

Stitch! stitch! stitch!

In poverty, hunger, and dirt,

And still with a voice of dolorous pitch,—

Would that its tone could reach the Rich!—

She sang this “Song of the Shirt!”

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.