On 7 February 2019, the Osler Library will host a vernissage to mark the opening of an exhibit by 2018 Larose-Osler Artist-in-Residence Caroline Boileau, “Corps qui hantent d’autres corps.” Boileau is the third artist selected for the residency, and the first with whom I worked throughout the entire process, from sitting on the awards committee to supporting her work at the library.

Despite having been at the Osler for less than a year and a half, I was on board while the first two artists-in-residence gave shape to their explorations of McGill collections; working with all three Larose-Osler recipients has been an inspiring and fulfilling experience. The exhibition of 2016 awardee Dr. Lucy Lyons had been postponed until the autumn of 2017. As Lyons was preparing her exhibit and invited me in as a co-curator, 2017 resident artist Loren Williams was in the final stages of her work with library materials and was starting to realize the vision of her exhibition.

The residency itself was the idea of local artist and paediatric neuropsychiatrist Michele Larose, who established the programme in the early weeks of 2016. As the gift agreement states, the Michele Larose-Osler Library Artist-in-Residence programme is intended for “visual artists visiting the university to create works that address contemporary and/or historical subjects in medicine and in the health sciences that are inspired by the rich and diverse collections held by the Osler Library and/or other sources at McGill.”

All three artists have brought to the residency, and thus to the Osler Library, a novel set of interests and perspectives. During a workshop that Williams did for a McGill seminar, she made a comment that has remained with me, and which illustrates the experience I have had with all three artists-in-residence: the beauty of a project can be as much in the process as in the final product. I have enjoyed the privilege of experiencing the beauty that is a part of each artist’s process. Each approach has been different, and each has helped me to imagine new possibilities for the sources that reside at the Osler Library.

Lucy Lyons: “Impossible Pathologies: re-fragmenting the archive.”

Dr. Lucy Lyons came to the Osler Library with a strong background in medical illustration, having completed a doctoral thesis at Sheffield Hallam University in 2009 on “Delineating disease: A system for investigating Fibrodysplasia Ossificans Progressiva.” That work was part of a much larger portfolio of artistic projects at medical museums and medical institutions, and opportunities to share through teaching.

A significant focus of Lyons’ work – and of the workshops she held for students at McGill while in residence at the Osler Library (described here) – was the effectiveness of drawing as a pathway to greater powers of observation. When one tries to draw, one sees details that might otherwise have been overlooked. This approach has clear implications for those who practice medicine and who might need to convey a clear picture of something that has not been observed or described before. As she said, how does one describe a circle if one has never seen one? It is more effective in that case to draw than to explain the concept of a circle using words; the same can be true when sharing medical knowledge.

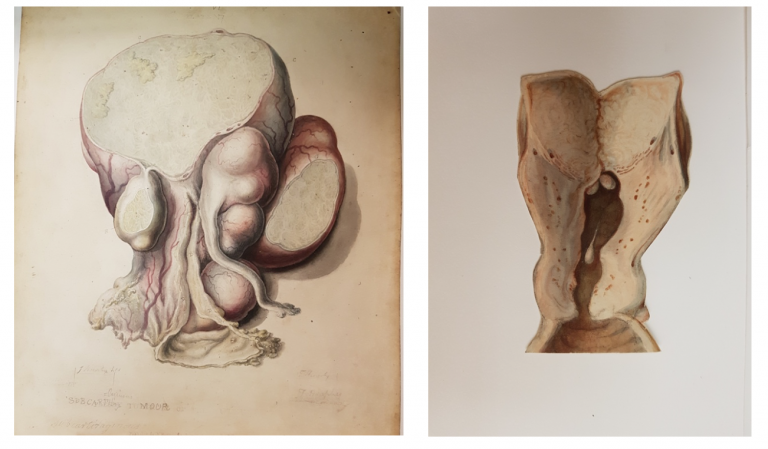

It was this keen sense of observation and wonder that led Lyons to a novel idea for her work and exhibition, which she named, “Impossible Pathologies: re-fragmenting the archive.” Among the items she studied at the Osler Library were six boxes of proof plates and original drawings relating to the morbid anatomy publications of physician Robert Hooper (1773-1835). Within these boxes, Lyons noticed images that were beautifully painted yet cut out. These cut-outs presented a source of temptation. She wanted to manipulate them, to see what happened if she turned them around or if she put various images together. As Lyons described it, seeing the cut-out shapes within the archival enclosures of the Hooper Collection led her to want to see how the various shapes fit together. The natural inclination to play, to puzzle, became the inspiration for her work.

This image, together with that to the right, inspired one of Lucy Lyons’ “impossible pathologies.” Robert Hooper. [Collection of original and coloured and other drawings of pathological specimens with accompanying text.] Osler Library, Osler Room folio, Bibl. Osl. 7574.

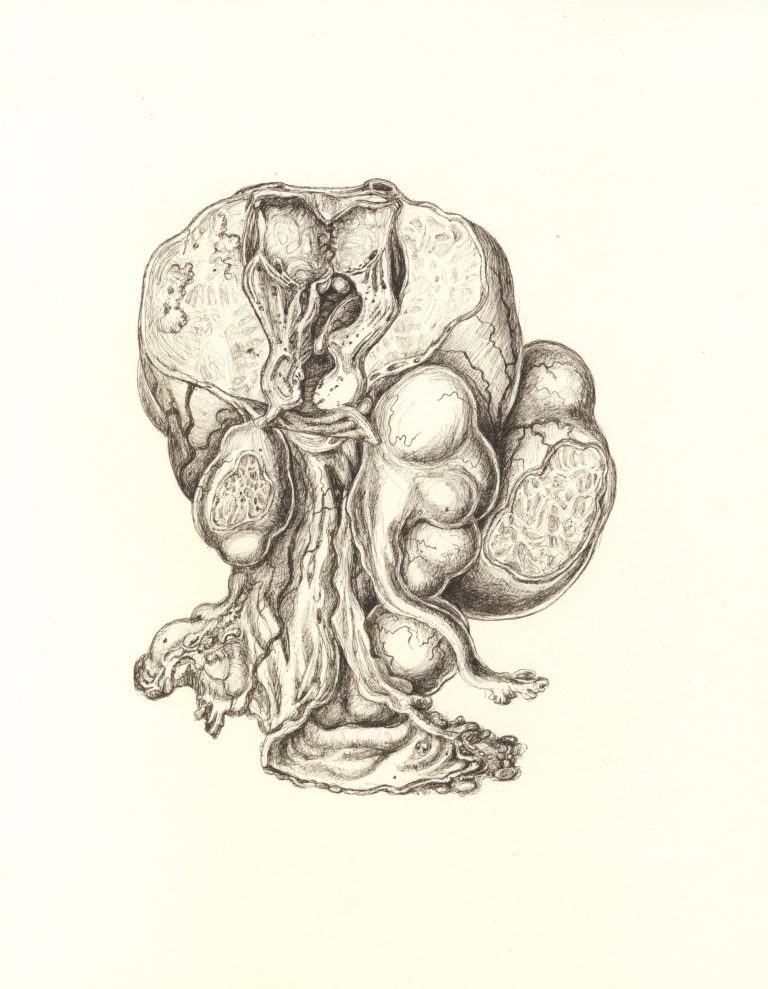

This creation was the result of bringing together the two Hooper illustrations, above. Credit: Lucy Lyons.

Lyons’ approach began with Hooper’s deconstruction, but the next step was to reconstruct. She put together cut-out shapes that did not necessarily belong together in a medical sense. Then, she drew her new creation in pen and ink. Since the composite drawings became images that looked strikingly realistic but were medically impossible, they became “Impossible Pathologies.” As she wrote on her website, the process was “like an analogue version of Photoshop.” Moreover, it was an idea she carried from archive to specimen as she moved from the Osler Library to the Maude Abbott Medical Museum. All of these ideas came together in a powerful and thought-provoking exhibit, displayed at the Osler Library from October – November 2017.

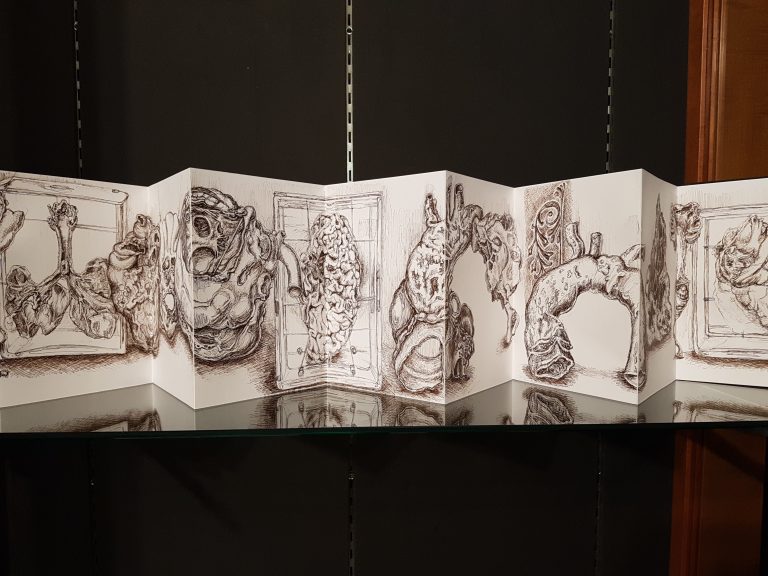

Selection from an accordion book of drawings by Lucy Lyons, inspired by items at the Osler Library and the Maude Abbott Medical Museum. Book credit: Lucy Lyons.

Loren Williams: “Materia medica.”

Loren Williams came to the Osler as a local artist whose primary medium is photography. She moved to Montreal from British Columbia in 1993 and continued to work in the city after receiving her BFA honours in photography from Concordia University. Part of what sets Williams’ work apart is her engagement with local history and local geography. Her exhibit “Materia medica,” which was on display at the Osler from December 2017- early May 2018, was a combination of two overlapping projects which traced elements of Montreal’s medical past.

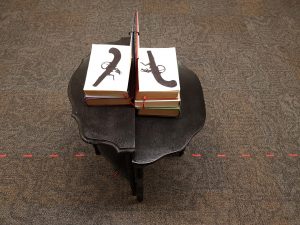

Entering the exhibition space, visitors were met with a dotted red line that extended across the entry space from a pair of nesting tables standing back to back, each of which displayed a book (one on medicine, one on jurisprudence), on which Williams drew a pistol on the flyleaf. Following the red line in one direction, one came to a description on the wall of the April 1819 duel between a lawmaker, Michael O’Sullivan, and Dr. William Caldwell, over opposing visions of a new hospital, which received its charter as the Montreal General Hospital a few years later.

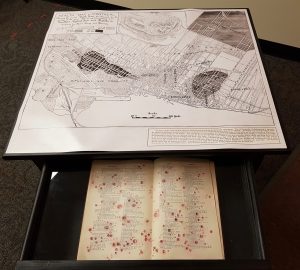

Elsewhere within the exhibit, she recreated an old epidemiological map of the city on a table top. Within the drawer of the table was a book with red spots to represent smallpox pustules. While the exhibition was running, Williams would add spots to the book, so that the discerning repeat visitor might notice the worsening of the epidemic (see gif, below). The map in the smallpox display provoked thought about which of the city’s quarters were most affected by epidemic disease in the 19th century, and what those neighbourhoods are like today.

While the book had begun with only a few spots (see the image on the left), by the time “Materia medical” closed, the book looked very sick indeed with smallpox pustules, shown here against an epidemiological maps wherein black areas were those most affected by infectious disease.

There were other ways in which Williams’ work encouraged engagement with local surroundings. The map in the smallpox display provoked thought about which of the city’s quarters were most affected by epidemic disease in the 19th century, and what those neighbourhoods are like today. Similarly, Williams created several cyanotypes using plants, which inspired reflection upon the medicines used by the First Peoples who inhabited the land where Montreal now sits, and knowledge of local medicinal plants as shared with early settlers.

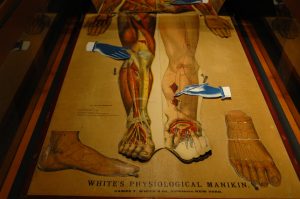

There were other aspects of “Materia medica” that highlighted a more personal interaction with historical detail. For instance, Williams included in her exhibit the life-size White’s Manikin, a male flap anatomy figure that folds into a wooden box. In this case, she took this anatomical atlas and added in female hands holding scalpels, which both accentuated the act of anatomizing while also giving a place to women in the history of medicine. Given Williams’ interest in using immediate surroundings as an active part of her art, one wonders if this display of female surgeons demonstrated in a nineteenth-century paper male manikin might also be a comment upon the immediate surroundings of the McGill Medical Faculty, which turned down Maude Abbott’s petition for the admittance of women in 1889, and did not have a graduating medical class that included females until 1922.

Williams created cyanotypes of local medicinal flora, which she juxtaposed with maps and medical artifacts.

White’s Physiological Manikin (1886), with the addition of female hands drawn and placed by Loren Williams.

It was from this mapping of body, population and geography that Loren Williams focused on a more singular aspect of Montreal’s medical history for the Larose-Osler artist residency. Using 18th to 20th century maps of Montreal, Williams located early medicinal gardens, often situated on hospital grounds, and researched the plants that were grown in them. This research led to the medicines used by the First Peoples who inhabited the land where Montreal now sits, and knowledge of local medicinal plants as shared with early settlers. Williams visited the sites of the early gardens, several of which still exist today and created images of plants using an early photographic process called Cyanotype.

Like the many layers of the White’s anatomical manikin, this botanical form of time travel revealed the multiple layers of Montreal’s medical history. With the city’s origins connected to the St. Lawrence River and the area that is now called Old Montreal, it is perhaps not surprising that plants used by the First Peoples would be found there and that in the 17th century it was the site of the first hospital and its large gardens. Throughout the 19th century this area was particularly affected by serious epidemic disease, and an area called Windmill Point was used for quarantine. In her research, Loren Williams discovered that Windmill Point, in the early 19th century, was also a popular location for pistol duels, including a certain dispute over a new hospital. After visiting the site, she reported that it is now quite overgrown, including wild rose, clover, thistles, lilies, pine trees and various other plants used since ancient times for their medicinal properties.

Caroline Boileau: “Corps qui hantent d’autres corps.”

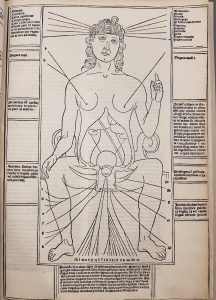

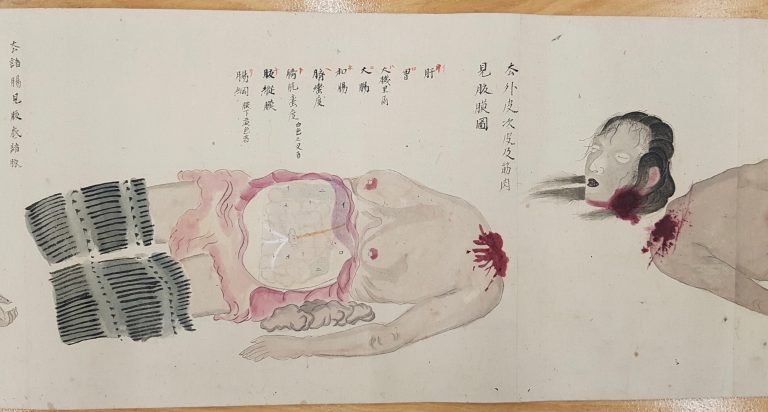

2018 Larose-Osler artist-in-residence, Caroline Boileau, describes herself as an artist who takes a multidisciplinary approach and works from a feminist perspective. At the Osler, adopting a feminist outlook has translated into a keen interest in the female form. The items she has looked at have run the gamut from medical instruments (surgical and obstetrical) to books and manuscripts. There has been the very open yet imprecise woman depicted in a full-page woodcut in Ketham’s Fasciculus medicinae (1500) and the executed pregnant female convict whose head appears positioned to witness her own dissection in a Japanese scroll from c. 1800. There were also grand eighteenth-century elephant folio volumes depicting the gravid uterus: Smellie’s A sett of anatomical tables, with explanations, and an abridgement, of the practice of midwifery (1754 and 1761), Jenty’s Demonstratio uteri praegnantis mulieris cum foetu…(1761), and Hunter’s Anatomia uteri humani gravidi tabulis illustrate (1774).

Woodcut of a woman, depicting female anatomy and outlining signs of conception. Johannes de Ketham, Fasciculus medicinae, Venice, 1500. Osler Library, Osler Room folio WZ230 K43f 1500.

An executed female convict appears to watch her own dissection. Source: Namisō Hōshi kai keiyo fu shi no zu [Osaka, ca. 1800]. Osler Library, Osler Room folio QS N174 1800.

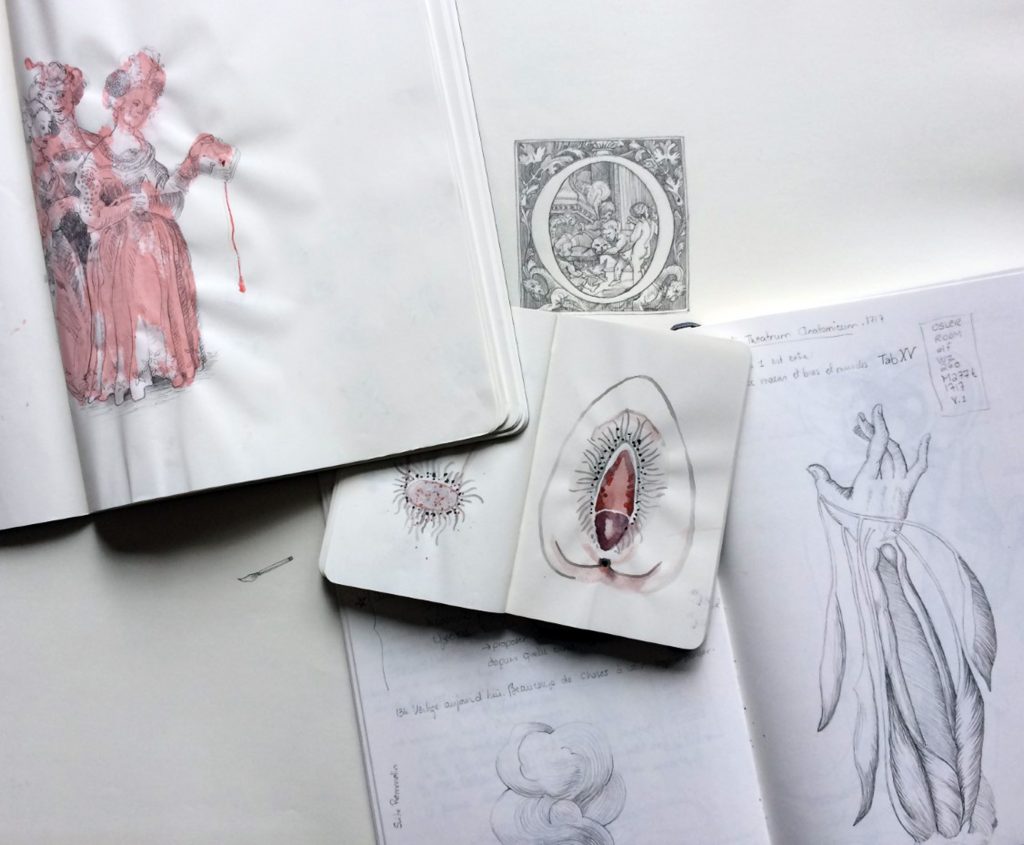

Boileau’s work has been an inspiration, partly because of the breadth of interaction she has displayed with her surroundings. In her drawings, her blog posts, her in-person discussions, and her Osler Library Newsletter article (pp. 4-5), she has highlighted the value of examining everything for its artistic potential. She has been in residence primarily to react to material from the Osler, but her interactions have shown how the texts and images in a collection can be a starting point.

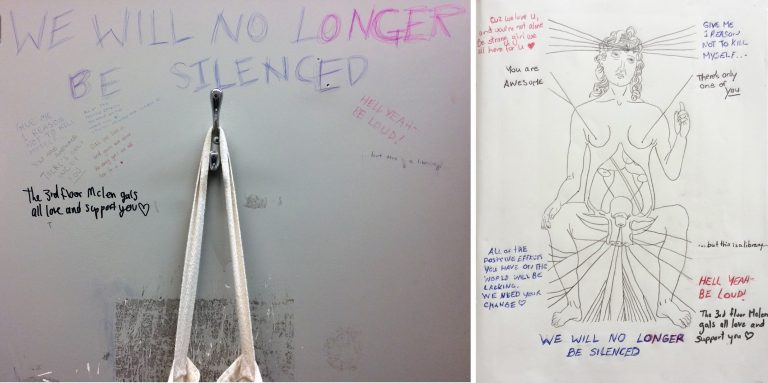

In addition to making novel use of medical historical sources, Boileau has revealed the importance of surroundings. Graffiti that she discovered in the stall of a washroom in the McLennan Library (the Osler’s current location), she later transformed in a drawing that brought together the messages of the graffiti with Ketham’s late mediaeval woodcut of a female figure. In a blog post otherwise without comment, a display case removed revealed the artistry found in what remained behind: an impression on the existing rug, and a large rectangle of an older, much lighter, section of carpet. In yet another blog post, she wrote in moving yet concise terms about the currently empty Osler Library space in the McIntyre Medical Building.

On the left, a photograph of graffiti on the door of a bathroom stall in the McLennan Library; on the right, a drawing based upon a woodcut in Johannes Ketham’s Fasciculus medicinae (1500), with the graffiti added. Caroline Boileau, 2018.

So far, there have been glimpses of what Caroline Boileau has planned for her upcoming exhibit. In the reading room cases, her art will be juxtaposed with the works that inspired it. There will be varied degrees of interaction, including a touch table display and the intermittent presence of Boileau herself. Suffice it to say, we are eager to see the final result, and welcome the viewing public to do the same. We look forward to seeing many of you at the 7 February 2019 vernissage to celebrate the opening of Caroline Boileau’s exhibit, “Corps qui hantent d’autres corps,” based upon the research and work she did as Michele Larose-Osler Library Artist-in-Residence; beyond February 7th, we hope you will return to further appreciate the exhibit, as well as the Library’s deep and varied holdings.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.