By Sophie Becquet, McGill Visual Arts Collection Student Intern (2024-)

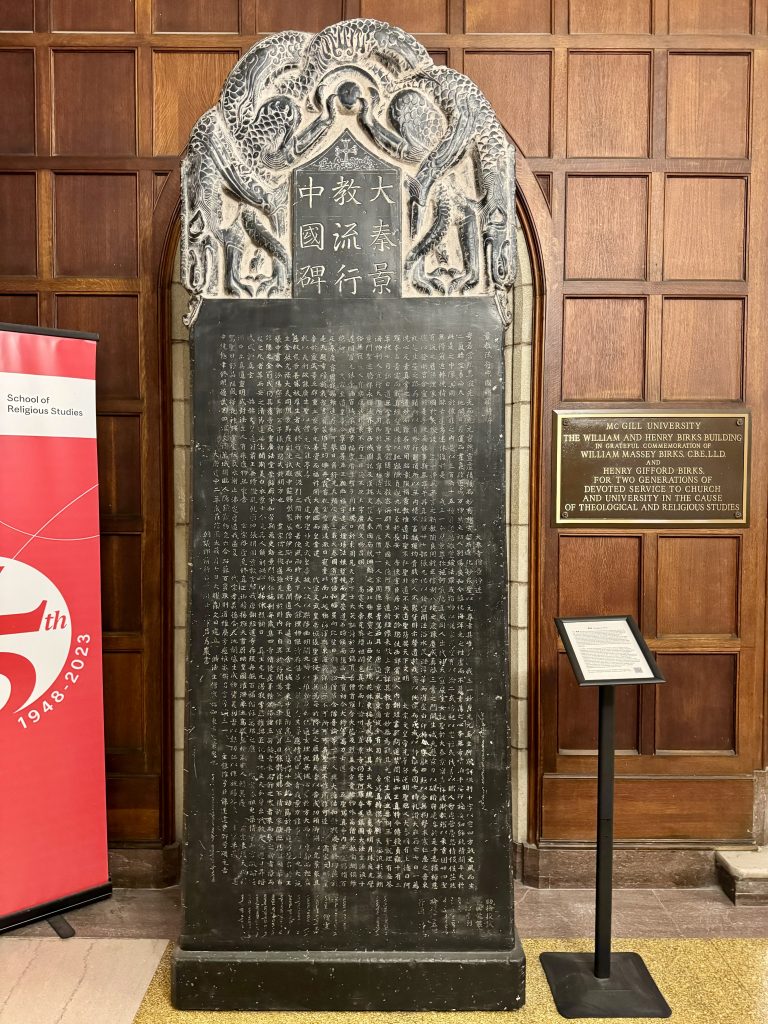

The Jingjiao (景教) Stele, or Xi’an Nestorian Stele, holds far more than meets the eye, bridging East and West through its cultural and religious significance and its extraordinary journeys across the globe. Erected in 781 during China’s Tang Dynasty, this 9-foot monument, inscribed in Chinese and Syriac, commemorates the arrival of Christian missionaries from Syria in 635. Emperor Taizong, who welcomed the missionaries, praised their religion as jing (景), meaning “luminous,” a term that gave rise to the name Jingjiao or “Luminous Religion.” Under his reign, this form of Christianity—shaped by the interaction of East Syriac traditions and Tang Chinese culture—flourished and became known to the West as “Nestorianism.” Over the centuries, the stele has been buried and unearthed, protected and pursued, and its story carried across continents—culminating in a McGill replica that has its own story to tell (Figure 1).[1]

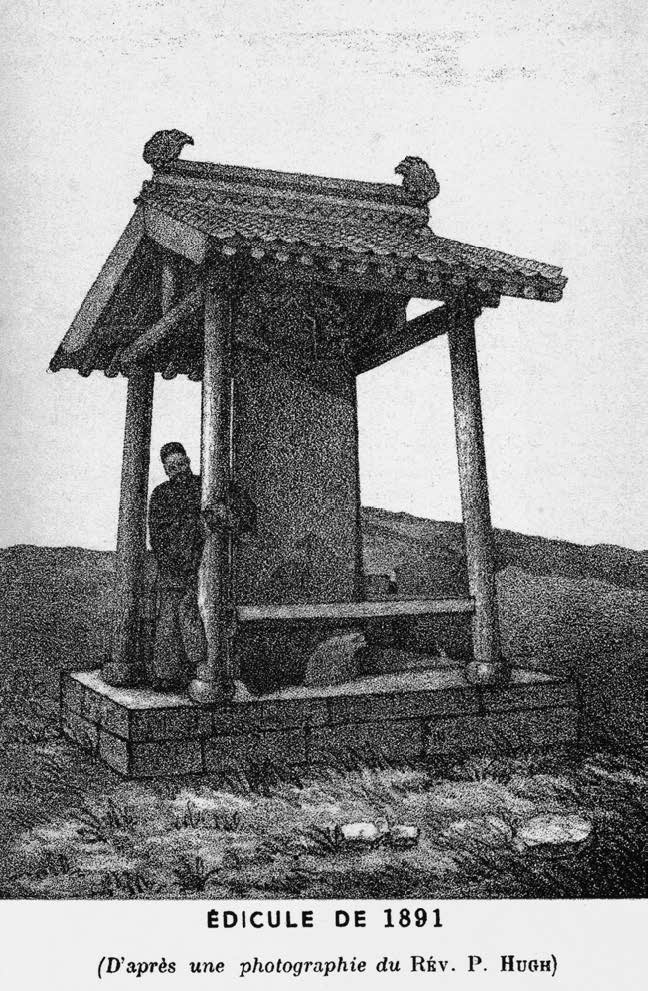

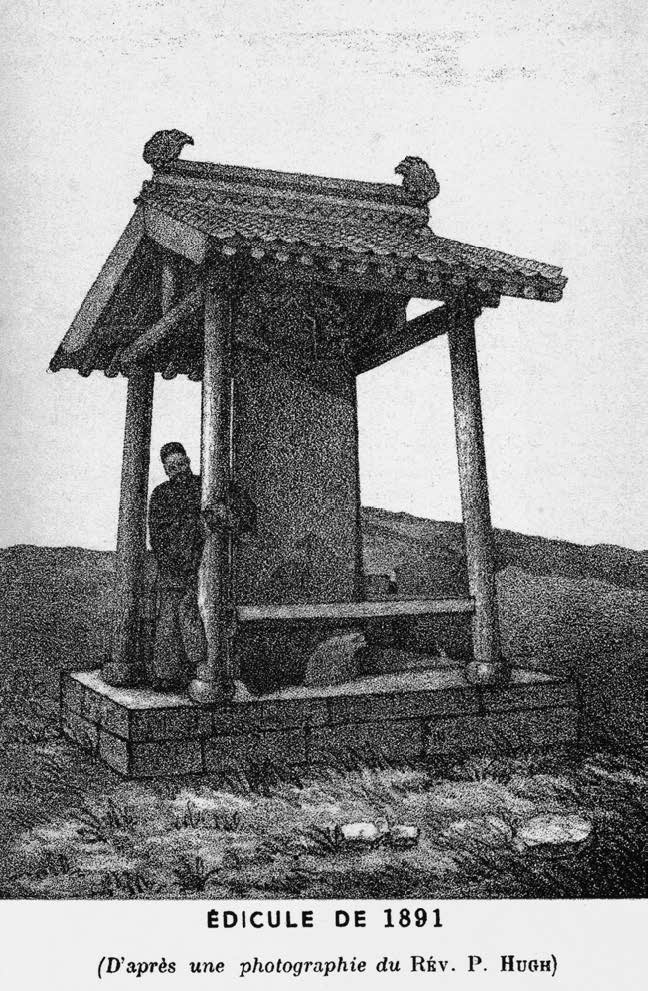

The Jingjiao Stele’s first chapter ended in the 9th century, when it was buried during the Huichang Persecution, an imperial campaign that sought to eradicate minority religions, including Christianity.[2] Hidden underground for nearly 800 years, the stele resurfaced in the late Ming Dynasty. Recognizing its significance, the local governor ordered it placed on a tortoise pedestal and protected with a roof,[3] entrusting its care to a nearby Buddhist monastery.[4] This stewardship continued until the early 20th century, when the stele caught the attention of the outside world.

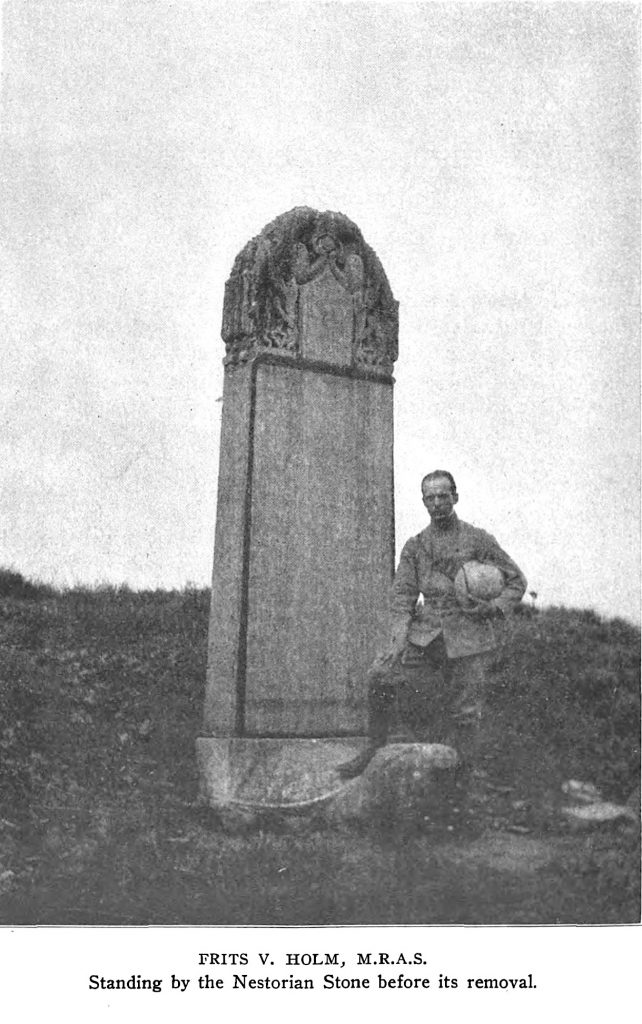

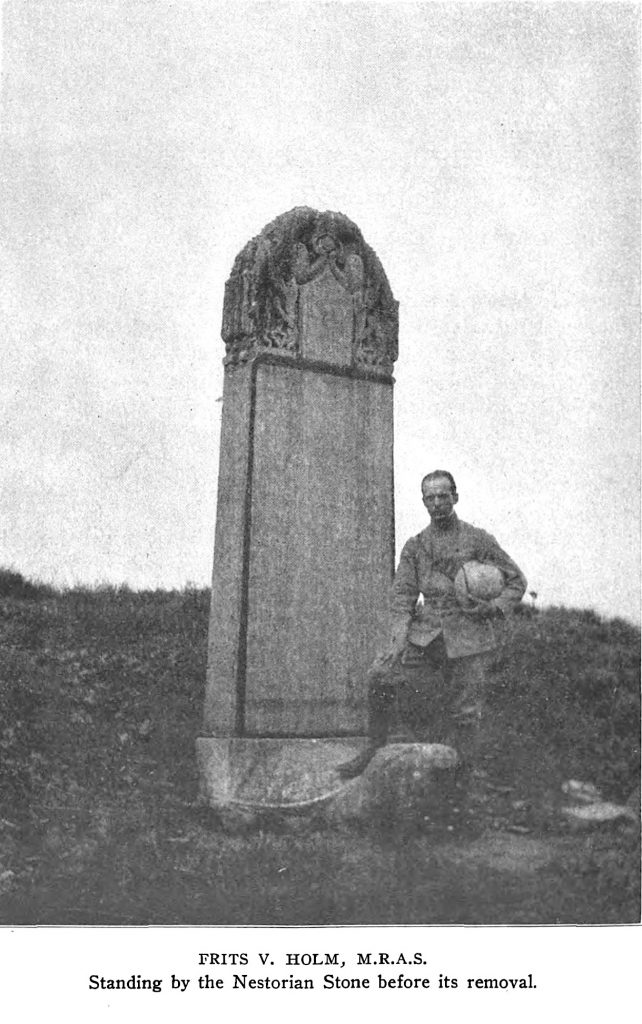

In 1907, Frits Holm, a young Danish adventurer with grand ambitions, arrived in China determined to claim the stele for a Western museum.[5] Holm, claiming that the “scientific world” of the West would better appreciate and care for the stele, planned to take it.[6] When local officials caught wind of his intentions, they quickly relocated the monument to the Stele Forest Museum in Xi’an, prompting Holm to commission skilled local artisans to create an exact replica. Using limestone from the same region and precise ink rubbings of the original, the artisans meticulously reproduced every detail, including the inscriptions, surface imperfections, and even the dents,[7] completing the replica in just 11 days.[8]

Transporting the replica out of China, however, proved to be far more complicated than its creation. Holm encountered significant resistance from local authorities, who were wary of allowing a cultural treasure—replica or not—to leave the country. Although Holm ultimately secured permissions with the help of the Russian minister who also represented the Danish government in China, the process was fraught with bureaucratic hurdles, delays, and tense negotiations. The replica was repeatedly “arrested and held in custody” as Holm described it, with officials fearing repercussions for approving its removal. Holm himself made multiple trips to Beijing to resolve the matter, while the replica endured a long and arduous journey to the coast—first by a specially built cart pulled by mules for 90 miles, then floated for over 200 miles down the Yellow River by boat.[9]

Holm initially intended to offer the replica to the British Museum, but they showed little interest. Undaunted, he shipped the two-ton stone to New York, where it found a temporary home at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Yet even there, the reception lacked enthusiasm. The museum’s director, Caspar Purdon Clarke, dismissed the replica as “so large a stone… of no artistic value in a museum of this sort.”[10] Instead of purchasing it, the MET agreed to display the stele on loan from Holm for eight years.[11] Eventually, Holm found a buyer in Julia May Crofton Leary, a wealthy New Yorker with a passion for philanthropy. In 1917, Leary purchased the replica and gifted it to Pope Benedict XV,[12] and Holm later claimed he personally delivered it to Rome, braving harassment from Austrian submarines along the way.[13] The replica has since resided in the Vatican’s Ethnological Museum.

The Vatican’s acquisition marked the beginning of a new chapter for the stele. With the Pope’s approval, plaster casts of Holm’s replica were produced in the Lateran Museum and distributed to academic institutions around the world. These casts, lighter and more portable, were particularly valued in academic circles for the history and cultural significance they carried, even as they were often viewed as inferior to the original in artistic value. One of these plaster casts was gifted to McGill University in 1921 to mark its centenary. Initially displayed in the Redpath Library alongside the prestigious Gest Collection of rare Chinese manuscripts, the stele was moved to the Birks Building in 1937 when the collection was sold to Princeton University, where it remained in a seminar room for decades.

Though many might dismiss it as “just a replica,” the stele has long been a meaningful connection to a larger legacy for Montreal’s Chinese community. Their dedication was made clear through a recent restoration effort led by Jason Tan, with support from the local Chinese community and the Groupe Boda. The project transformed the plaster cast to more closely resemble the original, darkening its once-stark white surface to evoke the weathered limestone appearance of the stele in Xi’an. In this transformation lies an important cultural perspective: a faithful resemblance to the original preserves its historical intentions, ensuring its essence remains accessible to contemporary audiences.

This approach highlights a significant difference in how cultures view replication and authenticity. In Chinese tradition, copying is a means of preservation and transmission. Through careful replication, the beauty, history, and artistry of a work can be safeguarded, ensuring that its legacy survives even if the original is lost or damaged. For centuries, artisans in China honed their skills by copying masterworks—an educational practice that emphasized both technical precision and respect for the source material. Replicas were not seen as mere imitations but as embodiments of cultural knowledge and continuity.[14] Even the alteration of originals, such as re-cutting portions of important stones, has been acceptable in the Chinese context when done for preservation purposes. In fact, the title caption of the original Jingjiao Stele itself has been re-cut in recent years to protect it and ensure rubbings can continue to be taken,[15] safeguarding its accessibility and legacy. In contrast, Western conservation standards have historically prioritized material originality, often hesitating to alter or reproduce artifacts for fear of diminishing their uniqueness. The story of the Jingjiao Stele and its replicas reveals how these perspectives can coexist, shaping our understanding of authenticity and preservation across cultures.

Today, the McGill replica stands proudly in the foyer of the Birks Building, not as a simple copy but as a vessel of history and cultural exchange. Its journey—from Tang Dynasty China to 21st-century Montreal—reflects the many hands and minds that have made it possible for it to be here on campus and viewed by audiences today: the Tang artisans who carved the original, the Chinese craftsmen who recreated it, Frits Holm who propelled it into global view, and the Montreal Chinese community who have attentively restored it. Whether original or replicated, the Jingjiao Stele preserves a story of faith, craftsmanship, and the cultural interactions that have shaped its legacy.

I am grateful to David Mitchell, Max Stern Fellow in 2016 at the Visual Arts Collection for his detailed research report tracing the provenance of McGill University’s cast. His bibliography was an important starting point for my research.

[1] Fig 1. McGill University’s plaster cast replica of the Jingjiao Stele after restoration, 2024.

[2] Anastasia McGrath, “China’s Buried Christian History,” Sapientia, February 10, 2021, Center on Religion and Culture at Fordham University, https://crc.blog.fordham.edu/arts-culture/chinas-buried-christian-history/.

[3] Fig. 2. Engraving after a photograph of the monument with a shelter built in 1891, from Henri Havret, La stèle chrétienne de Si-ngan-fou, vol. 2, facing p. 162. National Taiwan University Library, reproduced in Michael Keevak, The Story of a Stele: China’s Nestorian Monument and Its Reception in the West, 1625–1916 (Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 2008), 113.

[4] David Emil Mungello, Curious Land: Jesuit Accommodation and the Origins of Sinology (Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 1989), 168.

[5] Fig. 3. Photograph of Frits Holm with the Jingjiao Stele, from Frits Holm, The Nestorian Monument: An Ancient Record of Christianity in China (New York: John Lane Company, 1909), 22.

[6] Frits Holm, My Nestorian Adventure in China: A Popular Account of the Holm-Nestorian Expedition to Sian-Fu and Its Results (New York: Fleming H. Revell Company, 1923), 24.

[7] “The Nestorian Stone’s Message of Centuries.” The New York Times, July 12, 1908. https://nyti.ms/3YEiWb6.

[8] Michael Keevak, The Story of a Stele: China’s Nestorian Monument and Its Reception in the West, 1625–1916 (Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 2008), 118.

[9] “The Nestorian Stone’s Message of Centuries.” The New York Times, July 12, 1908. https://nyti.ms/3YEiWb6.

[10] Michael Keevak, The Story of a Stele: China’s Nestorian Monument and Its Reception in the West, 1625–1916 (Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 2008), 118.

[11] Frits Holm, My Nestorian Adventure in China: A Popular Account of the Holm-Nestorian Expedition to Sian-Fu and Its Results (New York: Fleming H. Revell Company, 1923), 310.

[12] “Mrs. George Leary: Honored by Pope Benedict XV for Services to the Church.” The New York Times, July 5, 1935. https://nyti.ms/4fE7Jhl.

[13] Frits Holm, My Nestorian Adventure in China: A Popular Account of the Holm-Nestorian Expedition to Sian-Fu and Its Results (New York: Fleming H. Revell Company, 1923), 320.

[14] Byung-Chul Han, “Why, in China and Japan, a Copy Is Just as Good as an Original,” Aeon, March 8, 2018, https://aeon.co/essays/why-in-china-and-japan-a-copy-is-just-as-good-as-an-original.

[15] Kenneth Starr, Black Tigers: A Grammar of Chinese Rubbings (Seattle and London: University of Washington Press, 2008), 192.

Le parcours de la stèle Jingjiao : de la Chine des Tang à Montréal

Par Sophie Becquet, stagiaire à la Collection d’arts visuels de l’Université McGill (2024-)

La stèle Jingjiao (景教), ou stèle nestorienne de Xi’an, est bien plus qu’un simple objet. Par son importance culturelle et religieuse et ses formidables pérégrinations à travers le monde, elle jette un pont entre l’Orient et l’Occident. Érigé en 781, à l’époque de la dynastie chinoise Tang, ce monument de 2,8 mètres de hauteur, qui porte des inscriptions gravées en chinois et en syriaque, commémore l’arrivée des missionnaires chrétiens de Syrie en 635. Ceux-ci ont été accueillis par l’empereur Taizong, qui a fait l’éloge de leur religion, la qualifiant de jing (景), mot qui signifie « lumière » et qui est à l’origine du nom de la stèle, Jingjiao ou « religion de la lumière ». Sous le règne de cet empereur s’est propagée une nouvelle forme de christianisme, au croisement des traditions syriaques orientales et de la culture chinoise Tang, connue en Occident sous le nom de « nestorianisme ». Au fil des siècles, la stèle a été successivement enfouie, déterrée, protégée et convoitée, et son histoire s’est répandue sur tous les continents. L’une de ses répliques est parvenue jusqu’à l’Université McGill et son périple vaut la peine d’être raconté (figure 1)[1].

Au IXe siècle, le premier chapitre de l’histoire de la stèle Jingjiao a pris fin lorsque celle-ci a été enterrée pendant la persécution de Huichang, campagne impériale visant à éradiquer les religions minoritaires, y compris le christianisme[2]. Cachée sous terre pendant près de 800 ans, elle a été retrouvée à la fin de la dynastie Ming. Conscient de sa valeur, le gouverneur local a ordonné qu’elle soit placée sur un piédestal en forme de tortue et protégée par un toit[3]. Il en a confié la garde à un monastère bouddhiste voisin[4], qui s’est acquitté de sa mission jusqu’à ce que la stèle attire l’attention de l’Occident, au début du XXe siècle.

En 1907, Frits Holm, jeune aventurier danois aux grandes ambitions, est arrivé en Chine, déterminé à rapporter la stèle pour l’offrir à un musée[5]. Affirmant que le « monde scientifique » occidental saurait mieux apprécier et prendre soin de la stèle, Frits Holm avait l’intention de s’en saisir[6]. Lorsque les autorités locales ont eu vent de ses intentions, elles ont rapidement transféré le monument au musée de la Forêt de stèles de Xi’an. Le Danois en a alors commandé une réplique exacte à des maîtres artisans locaux qui, en utilisant un estampage précis et de la pierre calcaire provenant de la même région que l’original, ont reproduit méticuleusement chaque détail de la stèle, y compris les inscriptions, les imperfections de surface et même les marques d’usure[7], en seulement 11 jours[8].

Toutefois, il s’est avéré beaucoup plus compliqué de faire sortir la réplique de Chine. Frits Holm s’est heurté à une forte résistance de la part des autorités locales, qui hésitaient à laisser un trésor culturel franchir les frontières du pays. Bien que les autorisations nécessaires aient finalement été obtenues avec l’aide du ministre russe qui représentait également le gouvernement danois en Chine, le processus a été semé d’embûches bureaucratiques et a donné lieu à des retards et à des négociations tendues. La réplique a été plusieurs fois « arrêtée et mise en détention », comme l’a écrit son propriétaire, les fonctionnaires craignant des représailles après avoir autorisé sa sortie du territoire. Frits Holm s’est rendu à plusieurs reprises à Pékin pour tenter de régler les difficultés. Pendant ce temps, la réplique a suivi un long et pénible périple jusqu’à la côte, d’abord dans un chariot spécialement conçu pour elle, tiré par des mulets sur 145 km, puis à bord d’un bateau, pour un trajet de plus de 320 km sur le fleuve Jaune[9].

Frits Holm avait l’intention d’offrir la réplique au British Museum, mais celui-ci n’a manifesté que peu d’intérêt. Loin de se décourager, il a expédié la pierre de deux tonnes au Metropolitan Museum of Art de New York. Même à cet endroit, l’accueil a été peu enthousiaste. Le directeur du musée, Caspar Purdon Clarke, a refusé d’acheter la réplique, la qualifiant de « pierre trop imposante… et sans valeur artistique pour un tel musée »[10]. Il a plutôt accepté de la garder à titre de prêt et de l’exposer au musée pendant huit ans[11]. Enfin, en 1917, Frits Holm a trouvé preneuse pour la stèle : Julia May Crofton Leary, grande philanthrope new-yorkaise, s’est portée acquéreuse de la réplique et en a fait cadeau au pape Benoît XV[12]. Plus tard, Frits Holm a affirmé l’avoir livrée lui-même à Rome, après avoir esquivé les attaques répétées des sous-marins autrichiens en cours de route[13]. La réplique se trouve depuis au musée ethnologique du Vatican.

L’acquisition de la pierre par le Vatican a marqué le début d’un nouveau chapitre dans l’histoire de la stèle. Avec l’accord du pape, des moulages en plâtre de la réplique de Frits Holm ont été réalisés au musée du Latran, puis distribués à des établissements universitaires du monde entier. Plus légers et plus faciles à transporter, ces moulages étaient particulièrement appréciés dans les milieux universitaires pour leur importance historique et culturelle, même s’ils étaient souvent considérés comme de moindre valeur que l’original sur le plan artistique. En 1921, l’un de ces moulages en plâtre a été offert à l’Université McGill à l’occasion de son centenaire. D’abord exposée à la Bibliothèque Redpath aux côtés de la prestigieuse collection Gest de manuscrits chinois rares, la stèle a été transférée au Pavillon Birks en 1937, lorsque la collection a été vendue à l’Université de Princeton. Elle est demeurée dans une salle de séminaire pendant des décennies.

Bien plus qu’une « simple réplique », la stèle est depuis longtemps le symbole d’un riche passé pour la communauté chinoise de Montréal. Les récents travaux de restauration menés par Jason Tan, avec le soutien de la communauté chinoise locale et du Groupe Boda, témoignent clairement de l’importance qu’elle revêt. Le projet a permis de rendre le moulage en plâtre plus fidèle à l’original. En effet, sa surface autrefois d’un blanc éclatant a été assombrie afin de rappeler l’aspect calcaire patiné de la stèle de Xi’an. Cette transformation a une dimension culturelle importante : en donnant à la réplique une apparence qui rappelle celle de l’original, on a permis au public d’aujourd’hui de percevoir l’essence même du monument millénaire.

La modification de la réplique met en évidence une différence culturelle importante dans la conception des notions de reproduction et d’authenticité des œuvres. Dans la tradition chinoise, la copie est un moyen de préservation et de transmission. En reproduisant minutieusement une œuvre, on en sauvegarde la beauté, l’histoire et le caractère artistique. Ainsi, son héritage est préservé même si l’original a été perdu ou endommagé. Pendant des siècles, les artisans chinois ont perfectionné leur art, tant du point de vue de la précision technique que du respect du matériau d’origine, en copiant des chefs-d’œuvre. Les répliques n’étaient pas considérées comme de simples imitations, mais comme l’incarnation du savoir culturel et de la continuité[14]. Même la modification d’originaux, comme la regravure de parties de pierres importantes, est acceptée dans le contexte chinois lorsqu’elle est effectuée à des fins de conservation. En fait, on a récemment regravé le titre de la stèle Jingjiao originale pour le protéger et pour permettre des estampages ultérieurs[15]. On préserve ainsi son accessibilité et son héritage. En revanche, les normes occidentales en matière de conservation ont toujours privilégié l’authenticité matérielle. Il y a souvent une réticence à modifier ou à reproduire des artefacts par crainte d’en altérer le caractère unique. L’histoire de la stèle Jingjiao et de ses répliques illustre la coexistence de ces deux perspectives et éclaire notre compréhension des concepts d’authenticité et de préservation dans différentes cultures.

Aujourd’hui, la réplique de la stèle Jingjiao trône dans le hall du Pavillon Birks de l’Université McGill, non pas en tant que simple copie, mais comme vecteur d’histoire et d’échanges culturels. De la Chine de la dynastie des Tang au Montréal du XXIe siècle, de nombreuses personnes ont tracé la route du monument jusqu’au campus : les sculpteurs de l’époque des Tang qui ont fabriqué la stèle originale, les artisans chinois qui l’ont reproduite, Frits Holm, qui l’a fait connaître au monde, et la communauté chinoise de Montréal, qui l’a restaurée avec soin. Grâce à elles, la stèle peut maintenant être admirée de tous. Qu’il s’agisse de l’original ou d’une copie, la stèle Jingjiao témoigne de la foi, du savoir-faire et des interactions culturelles qui ont façonné son histoire.

Cet article a été rédigé à partir des recherches qu’a menées David Mitchell, stagiaire Max-Stern (2016), pour le compte de la Collection d’arts visuels. Dans son rapport détaillé, il retrace l’histoire du moulage en plâtre, de ses origines jusqu’à son exposition à l’Université McGill.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.