We got to know the curators of this exhibition a bit better. Here is a glimpse behind the scenes into the curatorial team that put together this exhibition. The exhibition is on through June 18th, so come and enjoy during opening hours on this final weekend!

Vikram Bhatt is Emeritus Professor at the Peter Guo-hua Fu School of Architecture at McGill University. He received his Masters of Architecture at McGill University in Minimum Cost Housing (1975), then worked as a researcher with Minimum Cost Housing Group (MCHG), and from 1988 to 2020 directed the activities of the Group.

Ipek Türeli is Associate Professor and Canada Research Chair in Architectures of Spatial Justice at the Peter Guo-hua Fu School of Architecture at McGill University. Her recent research interests include low-income housing and participatory design, civil protest and urban design, and campus landscapes and race.

Arièle Dionne-Krosnick is a Ph.D. student at the Peter Guo-hua Fu School of Architecture at McGill University. She previously worked as a Curatorial Assistant at the Museum of Modern Art, New York. Her current research centers on the urban protests of the civil rights protests movement that took place at, and around, swimming pools.

Every exhibition is a joint effort and we received essential support from Jennifer Garland, Head Librarian at Rare Books and Special Collections, and Archivist Tellina Liu at McGill Library. We were assisted by a team of students from the School of Architecture, including Ph.D. student Beatriz Takahashi and master’s students Abigail MacKenzie, Christopher Malouf, and Hannah Mansfield Thiessen.

What were your guiding criteria for choosing which pieces to include?

After spending some time reviewing materials in the library’s archival collections, we came up with three unifying themes we labelled “Upcycle,” “Harness,” and “Plan.” From the very beginning, the MCHG was invested in innovative ideas; over the years, these concepts evolved around the contemporary rubric of sustainability. They include experiments to use and reuse local materials, innovations with the sulphur blck, finding low-cost and environmentally conscious ways to reduce waste, harnessing solar power, limiting water waste, re-using water, low-cost sanitation, and building rooftop gardens. When they worked internationally, the group was focused on learning from how people really lived; and from there, developed context-appropriate and culturally sensitive designs, a radical planning idea at the time!

We also wanted to show how publications of various sorts were central to expanding the research practice and dissemination of the ideas of the MCHG. We selected pieces that not only reflected the group’s ideals but also had a distinct visual language. We chose pieces that were relatively more exciting and inviting for visitors to look at.

In the context of minimum cost housing, how did you ensure a diverse representation of projects and designs in the exhibition? Did you prioritize certain regions, architectural styles, or social contexts?

The MCHG had a really fun, exploratory, and innovative sense of the work they were trying to do and clear sustainability goals, and that’s reflected in their designs. The group produced work in diverse geographies and at varying scales ranging from building blocks to systems, and settlement plans. The international impact of the projects and the availability of visually rich materials from the library’s collection became determining factors in the final selection.

We were lucky to find lots of great materials on the sulphur blocks: including step-by-step guides for how to shape and mould the sulphur bricks, as well as original photographs of the test house they built on campus. Similarly, the group prioritized low-cost designs, self-help approaches, and the reuse of locally available materials: they designed new toilets, and water misters to reduce household water waste, and proposed all kinds of ways to implement urban agriculture. Third, moving up in scale, we highlighted the urban design and planning scale studies and designs the group developed.

The MCHG had a global outlook from the beginning. The founding director of the program, Alvera Ortega was already working on developing efficient and low-cost housing for under-resourced people around the world on United Nations missions when he was hired as a faculty member at McGill University’s School of Architecture in 1970. The students and faculty affiliated with the Group got to test their ideas on the McGill campus first. They got to work across Quebec and Canada in collaboration with local host communities. They also continued to pursue international work in Argentina, Sri Lanka, Uganda, the Philippines, Mexico, Nigeria, India, and China.

Among these we chose to highlight the work in India and China where they collaborated with local, embedded, institutional partners over several years leading to significant impact and international recognition—In China, it was a 13-year (1983-1996) collaboration with the Chongqing Institute of Architecture and Engineering and Beijing Institute of Architecture and Design; and in India, it was an 8 year (1984-1992) collaboration with the Vastu-Shilpa Foundation focused on the formulation of appropriate housing standards for housing developments.

What does the MCHG look like today? What initiatives or programs are the group involved in?

The MCHG is not an active group anymore, but we have been very lucky to have their archives preserved in the McGill Library as well as at the Canadian Centre for Architecture (CCA), where their work is still accessible to researchers. At McGill, we pulled from the Alvaro Ortega Fonds and the Witold Rybczynski Fonds: Rybczynski was an essential faculty member and the second director of the MCHG. We also obviously benefited from the personal collection of Vikram (Bhatt) who was the third and final director of the MCHG.

Innovations included in the exhibit include gems such as the mini mister to 5-gallon flush. What is one specific item or artifact that surprised you and why did it stand out?

The sulphur block developed by the MCHG is maybe the most well-known exploration by the group, and it was the focus of an exhibition at the Bauhaus Foundation in Dessau in 2020. Sulphur was not only a widely available natural material, primarily found in volcanic areas, but also a globally mined mineral. It was also one of the by-products of petroleum refineries and natural gas industries and easily accessible in several regions worldwide. For the MCHG, this made it an excellent waste material ripe for reinvention. Members experimented with sulphur-concrete and transformed it into interlocking building components that could be used as basic construction material to build walls, floors, and roofs. They also experimented with sulphur cookware, furniture, and sulphur-coated textiles. They discovered that magazine and newsprint images could be durably transferred onto the sulphur concrete surfaces: those images were a nice discovery.

Working with sulphur had its pitfalls, namely its insulation properties and flammability, but the MCHG saw this simply as one more challenge for experimentation. They hoped that these sulphur concrete blocks could be a more affordable self-build alternative to the commonly used Portland cement, but this never actually materialized as a popular building component.

There are many explorations today, too, around the topic of repurposing industrial waste material or growing organic substances as building materials in new build construction. We plan to run workshops during the October exhibition where students will get some hands-on experience and learn about some of these more recent explorations. We frame the experimentation that started with the MCHG as a living tradition at our School and on our campus. Stay tuned!

An exhibition like this one entails careful picking and choosing, resulting in many things being left out. In your research, what other interesting ideas did you encounter that didn’t make it into the final selection?

One of our original ideas was to highlight student work: many architects who studied in the MCHG developed thesis projects that turned into the official publications of the group. Research on sulphur, self-build housing, and sites and services, for example, was part and parcel of the MCHG mandate. We did end up including some of these materials, but unlike in an archival setting where you get to manipulate objects and spend a lot of time consulting and reading a thesis document, in an exhibition context, the thesis papers themselves were not as accessible at a glance.

Were there any particularly unconventional or outlandish ideas or designs that you came across during your research for this exhibition? Can you provide an example or two?

In the photographs showing the design for the sanitary unit, the viewer gets to see the transformation of the toilet into a multi-use object. The tank of the toilet is replaced with a water heater, which is topped with a little sink, and also has a shower hose attached: the image of the person bent over the sink to wash their hair is fantastic. It’s actually such a compact and smart water-saving device!

The publications also show all kinds of sources of inspiration for low-cost housing and reused and readapted materials. The publication “Use-It Again Sam” has some precedents that are humorously captioned like: “the home that Beer-built…for a beer-can house, the designer learned every little bit helps.” Some of the water-mister developments seem to have been inspired by existing design objects like “The Facial Beautifying Mist machine by Lady Schick”—a device from the 1960s, essentially a facial steamer—which used steam to create water vapour that condenses on the skin, without water waste.

Have any of these ideas been realized in real life and gained mainstream acceptance? Are there any success stories you can share?

It is impressive to see how many of the ideas explored by the MCHG team have been accepted in architectural and building practice today: energy conservation, water conservation, and recycling are widely practiced; the LEED norms reflect this. Urban agriculture is also widely practiced and is commonly accepted as a way to promote local, accessible, and sustainable food systems.

The “How the Other-Half Builds” studies conducted from the late 1970s to the late 1980s informed the award-winning Aranya housing project in Indore, India, designed by late Pritzker laureate B. V. Doshi. And that housing development is still home to more than 80,000 residents today!

What was the “spark” for this exhibition? Why are these projects important to showcase?

With this exhibition, we are going back to the source of many of the core concepts that form the backbone of sustainability in architecture—waste reduction, reuse and recycling, local and environmentally sensitive approaches and materials, low-cost building alternatives—and the pioneering research by the MCHG in these areas.

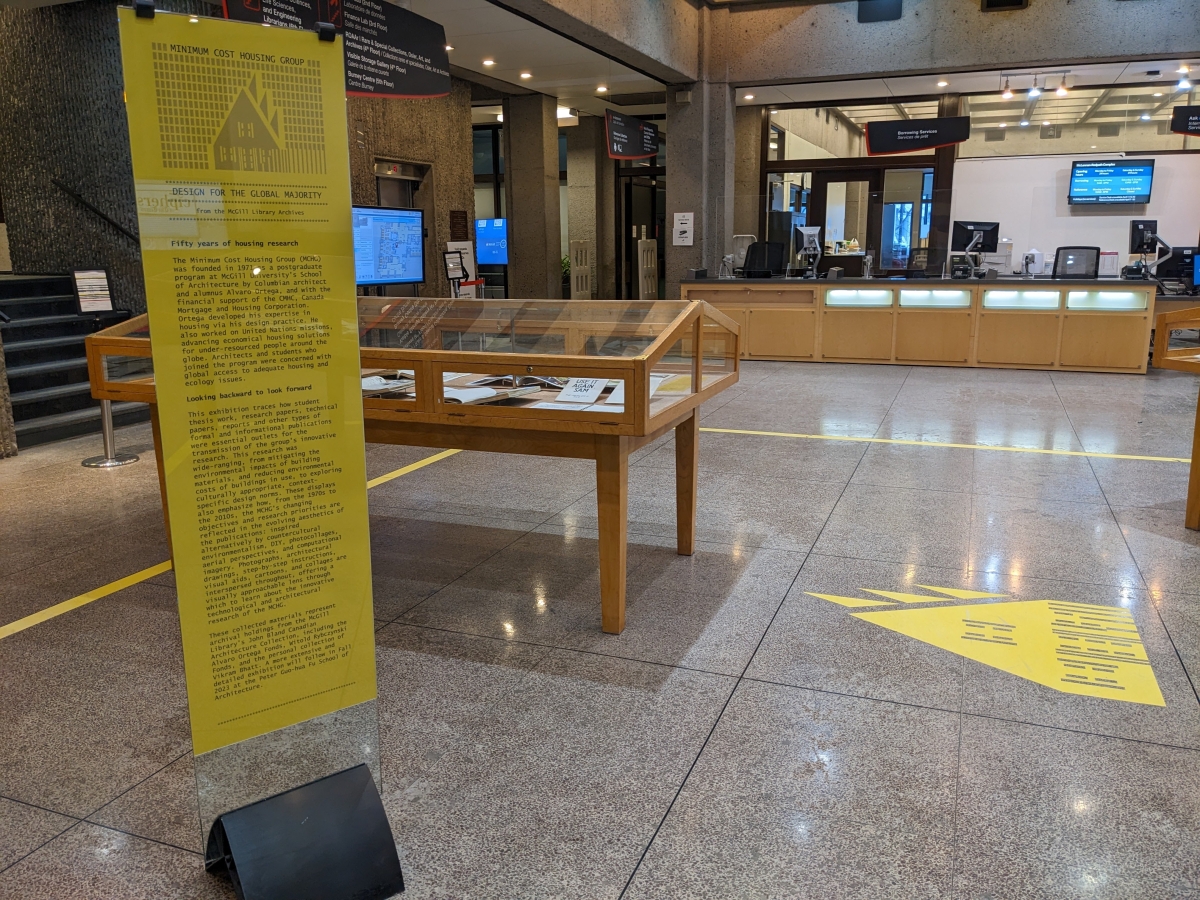

The Library exhibition was conceived as an introduction, a prelude to the larger and extensive Fall exhibition which will take place at the School of Architecture from 2 to 27 October 2023. This will be accompanied by workshops, guided gallery tours, and a symposium to coincide with the university’s Homecoming. The timing of this earlier library exhibition was scheduled so that it coincided with the Society of Architectural Historians annual conference which was held in Montreal this year. So not only our wider campus community got a glimpse of the MCHG’s work but also an international group of architectural historians had a chance to learn about the history of our School. We were pleased that the exhibition was seen by library patrons who would not necessarily step into the School of Architecture where we normally hold our exhibitions. Finally, the library exhibition features the wealth of materials available right here on-site and in the archives, and starts a conversation around the continued relevance and importance of sustainability in building practices.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.