This past Summer Chris Jones travelled from Scotland to spend one month in the Reading Room to investigate several rare editions from the Rare Books stacks attributed to the young poet, Thomas Chatterton (1752-1770). Professor Jones was the recipient of the McGill Raymond Klibansky Research Grant awarded in 2020, which had been delayed due to Covid-19. Now back in full-gear with students and researchers coming on site, we are eager to share a thought-provoking piece on the transmission of Chatterton’s writings published in the eighteenth century.

By Chris Jones, formerly of the University of St Andrews;

now ESRR Chair of English Literature at the University of Utah

Thomas Chatterton (1752-1770) can hardly be considered a household name today, even in the most literary of households. He is scarcely read even in university English departments, except perhaps on very specialist eighteenth-century courses. But there was a time when every lover of poetry in the English language knew and cherished his works. Keats thought him the writer of the ‘purest’ English language. Coleridge obsessed about him, endlessly re-writing his ‘Monody on the Death of Chatterton’ throughout the course of his life and Wordsworth referred to him as ‘the marvellous boy’. It would be only a slight exaggeration to say that he invented romanticism before romanticism, at least in English poetry.

Chatterton legend

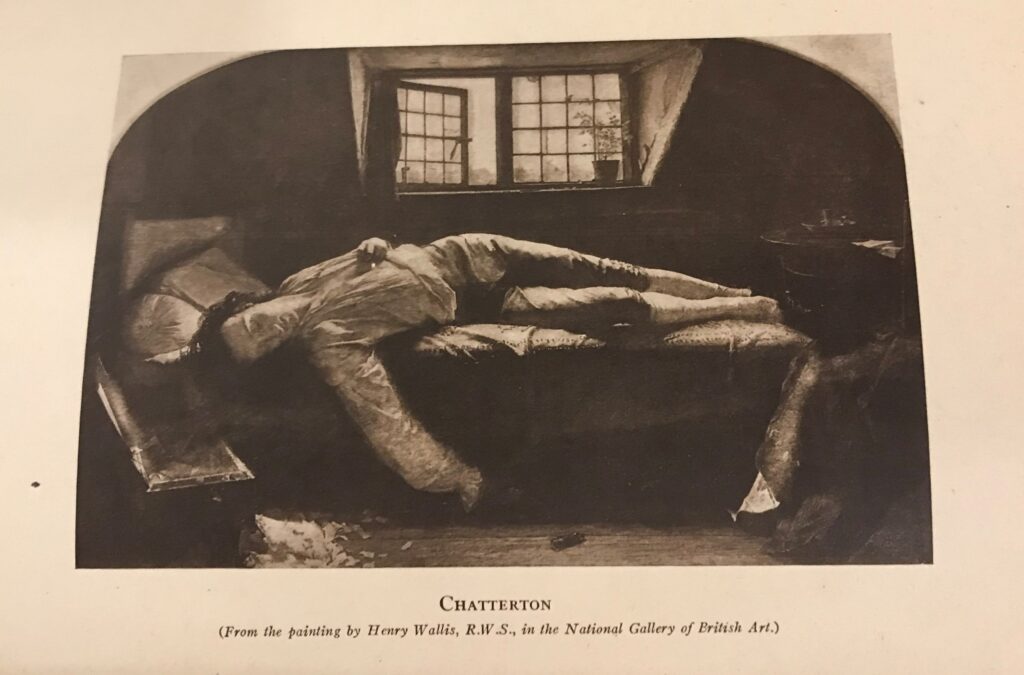

During the nineteenth century Chatterton was the subject of painting, plays, novels, operas and many of his poems were set to music. Victorian anthologists were accustomed to treat him as the peer and equal of Chaucer, Spenser and Milton, whereas today he is more likely to be omitted entirely from modern anthologies of English poetry.

This high regard in which Chatterton was once held is all the more remarkable given that he was largely self-educated (he reputedly taught himself to read from a black letter – or ‘gothic’ script – bible), that almost the entire body of his work was written within the space of around four years, and that he was dead at seventeen. On the 25th of August 1770, three months before his eighteenth birthday, Chatterton’s body was found in his attic room lodgings in Brook Street, Holborn London, the teenager having died of arsenic poisoning the night before; most authorities have since presumed this to have been an act of suicide. Rejected and sometimes ridiculed in his own lifetime by the literary gatekeepers of his day, ground down by poverty and starvation, in many ways Chatterton wrote the script of the misunderstood tortured artist who dies early, decades before the tragic celebrity of figures like Vincent van Gogh, Charlie Parker, Jimi Hendrix, Kurt Cobain and Amy Winehouse would cement this archetype as one of the most familiar tropes of modern popular culture.

Another way in which Chatterton anticipates an important strand of modern popular culture is that most of his oeuvre is an astonishingly ambitious imaginative exercise in medieval worldbuilding which prefigures that of Tolkien, with the same emphasis on linguistic detail (although he did not possess Tolkien’s rigorous professional knowledge of medieval languages).

Chatterton learned very early on that no-one was interested in publishing or paying for the poetry of a self-educated working-class boy from Bristol (most professional writers of the time were independently wealthy or had patrons whose support would free them from the vulgarity of having to earn money). But he did manage to make some money by faking ‘medieval’ heraldic coats of arms for the emerging nouveau riche classes of local business men in mercantile Bristol, professing that he had found his forged documents among the muniments of St Mary Redcliffe, a local medieval church where his father, who had died fifteen weeks before his birth, had been sexton (Chatterton probably did have access to some genuinely medieval manuscripts at St Mary Redcliffe, where he would play and study as a child).

Realising that if he wrote poetry in a pseudo-archaic English that he cribbed from early editions of Chaucer and other antiquarian books, and passed it off as the composition of medieval authors rather than himself, Chatterton managed to get his work published in local and national periodicals, such as The Town and Country Magazine, and earned a little money for ‘procuring’ the materials rather than authoring them.

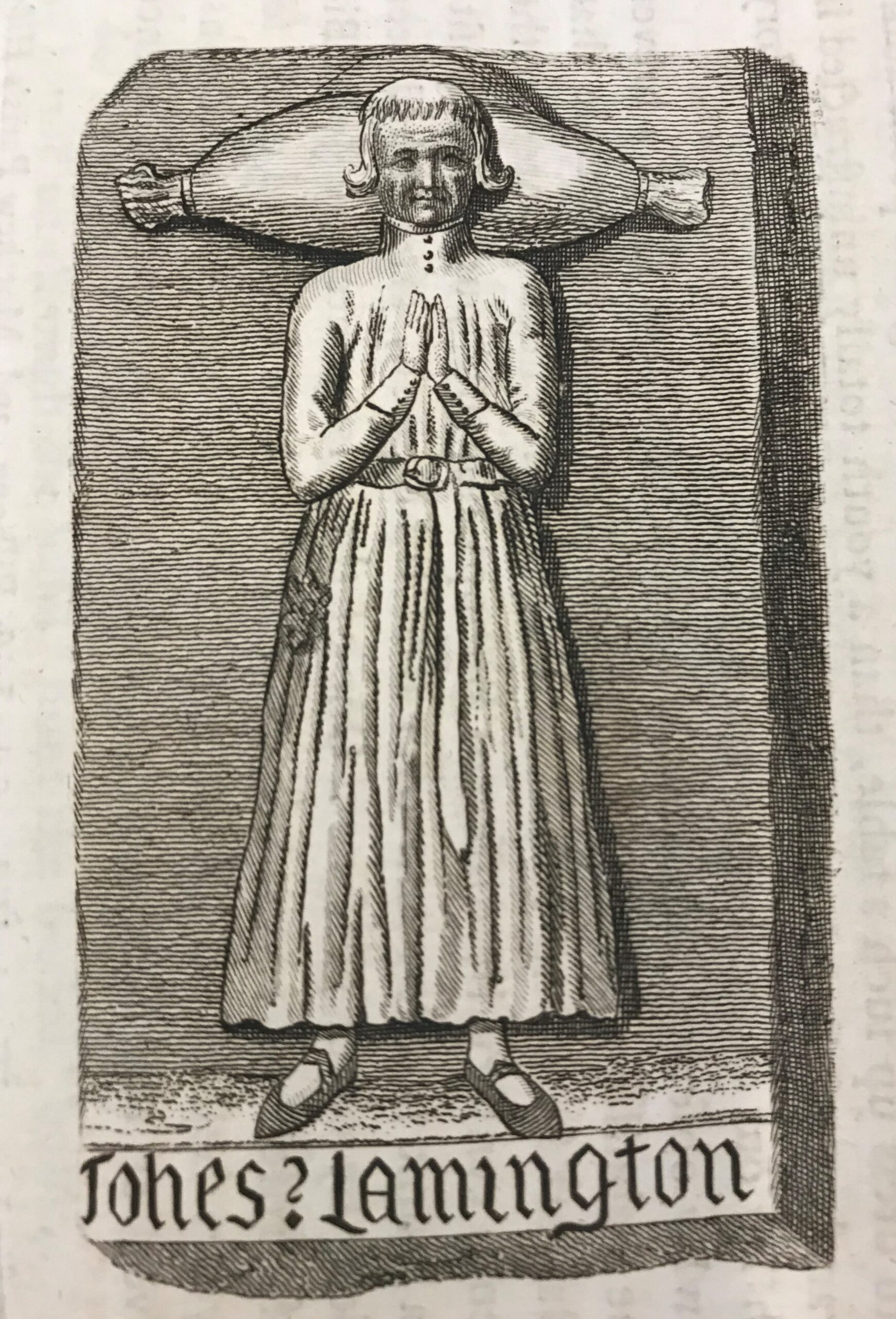

Soon Chatterton had created a whole literary milieu populated by real and imaginary characters from fifteenth-century Bristol, chief among whom was ‘Thomas Rowlie’, a poet-priest whom Chatterton invented to author many of his creations (equipping him with correspondence with the real poet John Lydgate, to make him more believable), and William Canynge, an actual historical figure who had been mayor of Bristol, as Rowley’s wealthy and generous patron (an obvious example of projected wish fulfilment on Chatterton’s part).

The Poems

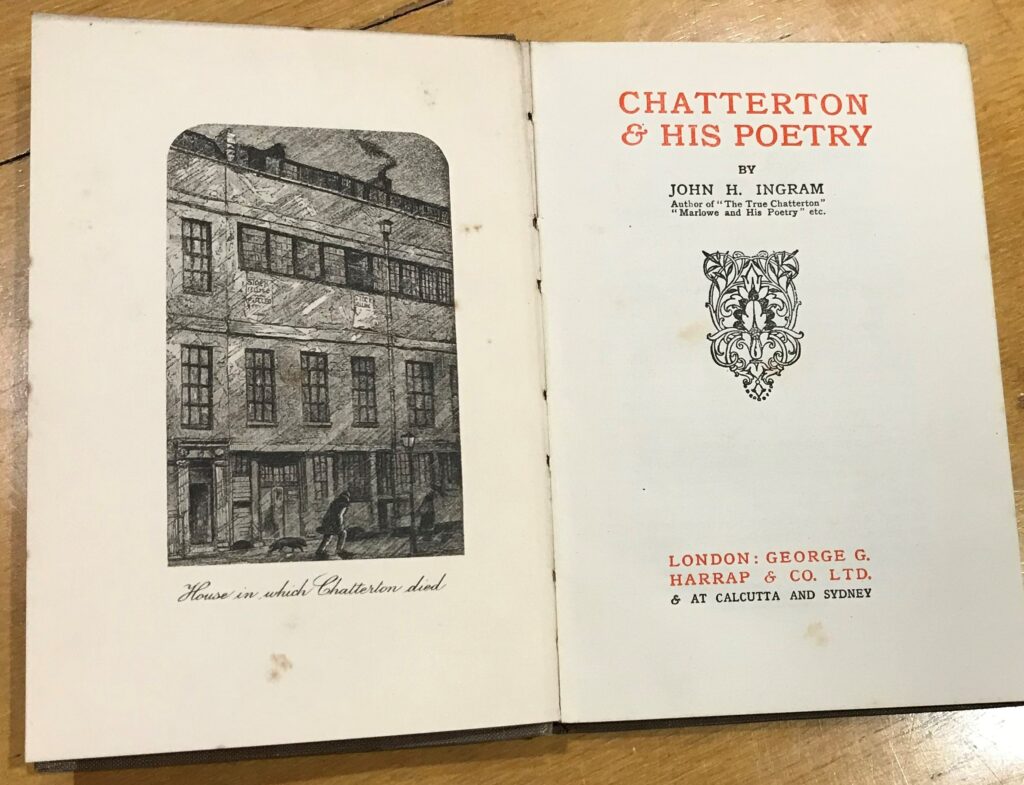

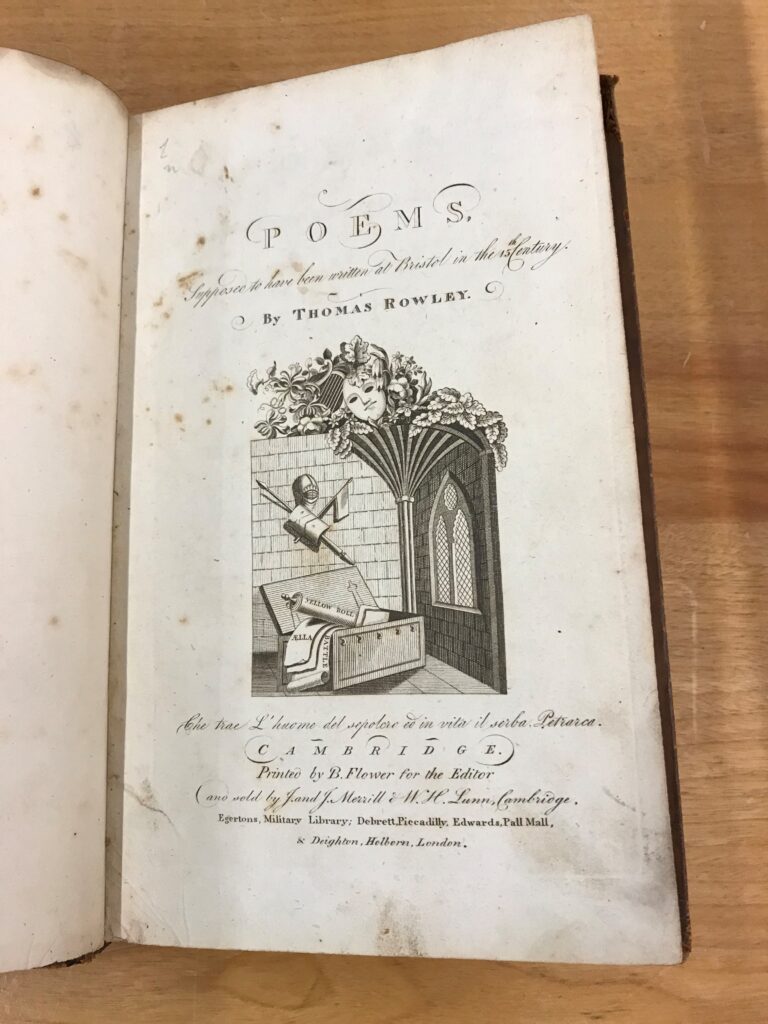

The rich and extensive collection of early publications and editions of Chatterton/Rowley’s poems held in McGill’s Rare Books and Special Collections library allows one to appreciate just how fluid and varied a body of work ‘Rowley’ (and a little later ‘Chatterton’) was in the formats in which it was presented to readers in the first decades of its reception.

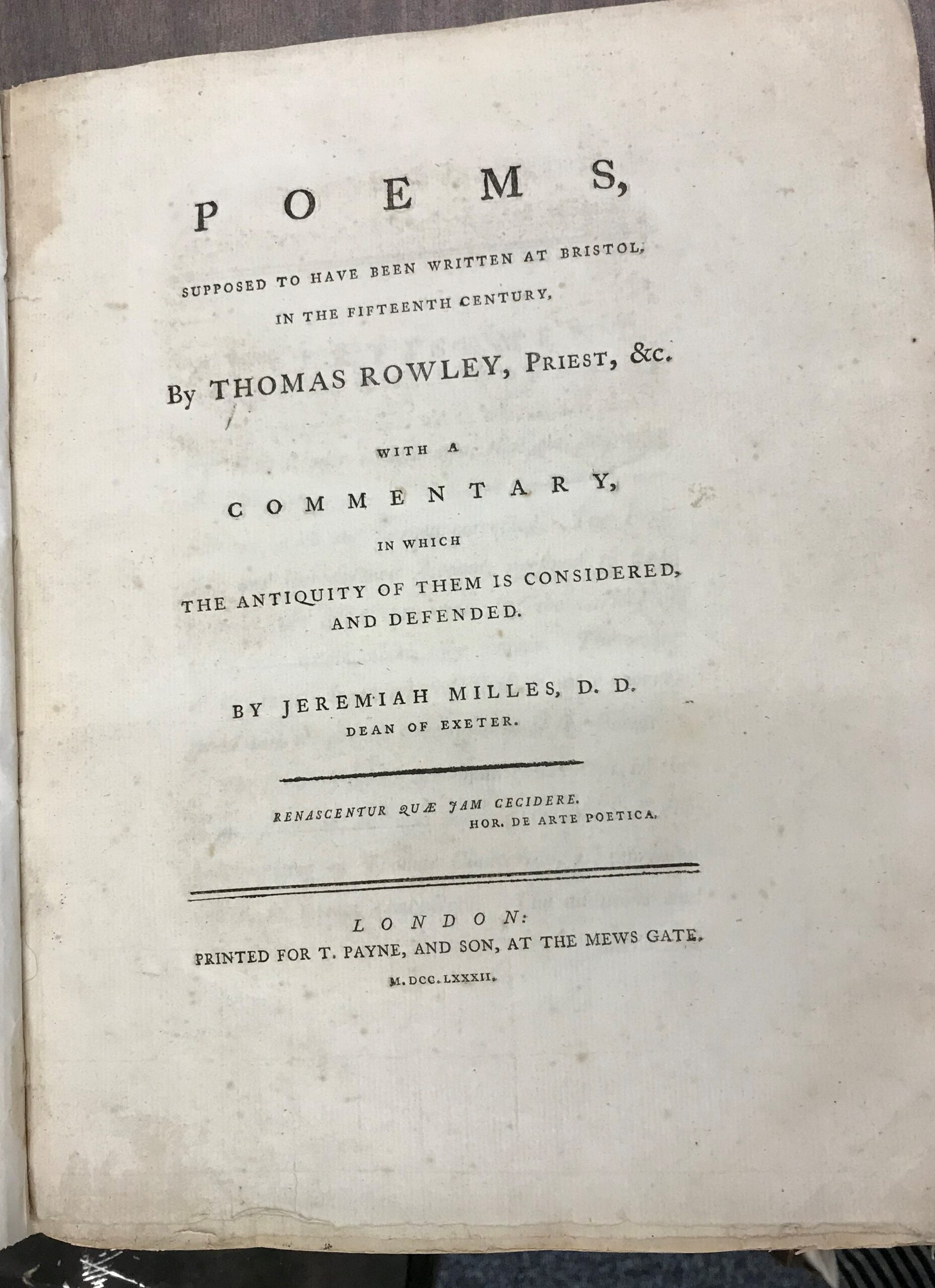

For instance, the contents of the fourth independent publication his work, in 1782, are largely reprinted from the first 1777 edition however, the order of those poems, as well as the explanatory materials to contextualize them, is entirely different. This volume is also the first in folio format, and lavished with illustrations and extensive footnotes – a luxury item that suggests the growth of the market among high-end readers of Chatterton/Rowley.

This is a headache for editors and textual scholars, who need to be able to fix a stable canon of work (several pieces in these early publications were dubiously attributed to the dead teenager), a stable form of words for each text, and a chronology of composition. To the scholar of literary history and reception, however, such problems provide rich opportunities for understanding. What my time at McGill, enabled by a generous Raymond Klibansky award, allowed me to appreciate and begin to document, is how much these early presentations of Chatterton’s work foreground not the pseudo-fifteenth-century compositional matrix of ‘Rowley’, but rather real and imaginary events and characters from the eleventh-century and earlier.

Indeed, much of the subject matter of Chatterton/Rowley is not late medieval, but pre-Conquest, or ‘Anglo-Saxon’, with Rowley imagined as the translator and transmitter, rather than maker, of materials of even older literary pedigree. This is the reason that the 1782 edition does not reset the poems of 1777 in the same order, for instance, but puts two ‘translations’ of an alleged contemporaneous poem on the Battle of Hastings at the head of its contents page.

The late eighteenth-century Chatterton was, in fact, not so much a medievalizing literary phenomenon as it was a Saxonizing one. This is salutary to think of, not only in how it re-frames Chatterton and our understanding of his influence on English romanticism, but also given that the idea and construction of ‘Anglo-Saxon England’ as an imaginary space is currently undergoing re-evaluation by scholars in view of its long historical imbrication with imperialism and white supremacy. Chatterton was perhaps the first writer to ‘Saxonize’ English poetry.

A quick update re the Thomas Chatterton Manuscript Project :

The website: https://www.thomaschatterton.com/ has been updated recently and is well worth a look.

The number of books written about Chatterton is large and I thought that a comprehensive list of biographies, most of which are available to read online, would be helpful : https://www.thomaschatterton.com/thomas-chatterton-biography-m2

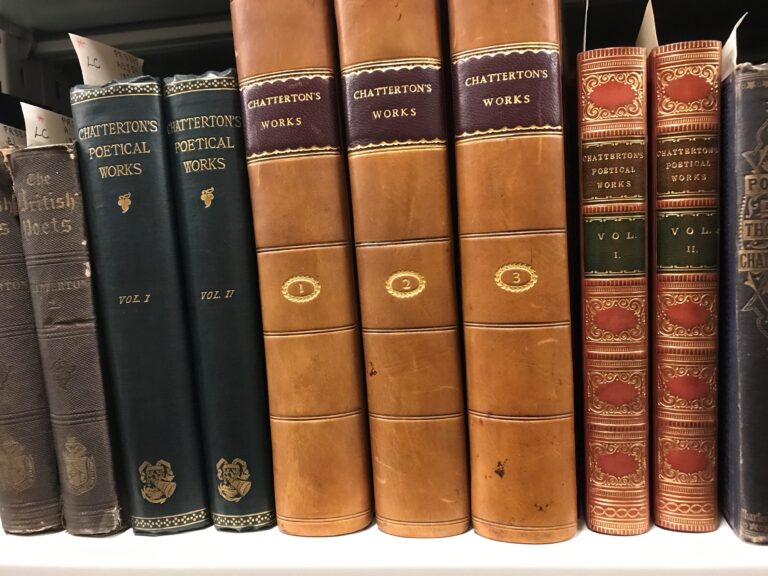

Also, it might interest your readers to know that the Chatterton books in your image at the start of your article are, from left to right, Walter Skeat’s two volumes, 1871;

The Works of Thomas Chatterton, in three volumes (Vol 1: His Life, by Gregory and Miscellaneous Poems; Vol 2: The Poems Attributed to Rowley; Vol 3: Miscellaneous Pieces in Prose), Edited by Southey, Cottle & Gregory 1803 ; finally,

The Poetical Works of Thomas Chatterton with Notices of his Life. No editor is named in either volume but we know that Charles Bonnycastle Wilcox was the editor.

OK, time to be honest, I am guessing a little on the first and third copies because similar covers were used on the Aldine edition (Skeat’s) as on the 1842 copies by Wilcox – anyway it is just a little bit of fun.

Hi Chris,

For me it is always a special delight to find someone writing about my favourite subject.

However,……..

‘However,’ is sometimes a scary way to start, but I felt I needed to write to point out that there are a few factual errors in your essay. I am a founding member of the Thomas Chatterton Society (2002 iteration) and now tend to write most of the articles on their facebook page. The chap who writes the website has not added anything for a long time, so that appears to be a lost cause. However, and this is a good however, I started the Chatterton Manuscript Project about ten years ago and continue to work towards a comprehensive source for everything Chatterton – this takes up a huge amount of my time, but still I am jealous that you spent a month working on Chatterton at McGill, you lucky devil! I am not a member of the University Classes (I am proud to say that my daughter is), so I have to fund everything myself, this is because, as you say, there is less interest in Chatterton these days. I dare say that my Chatterton collection is larger than McGill’s, which needs to be the case because I live in rural Ireland, and only have access to that fine resource, Bristol Reference Library, when I visit family in Bristol (I am a Bristol Boy, hence my interest in Chatterton). Anyway, to amend the little errors you might visit The Thomas Chatterton Manuscript Project website : https://www.thomaschatterton.com/

Best wishes

Richie Fenlon, The Thomas Chatterton Manuscript Project