by Jocelyn Campo, McGill Visual Arts Collection ARIA Intern (2023), Museum Database Assistant (2023-2024), Class of 2024

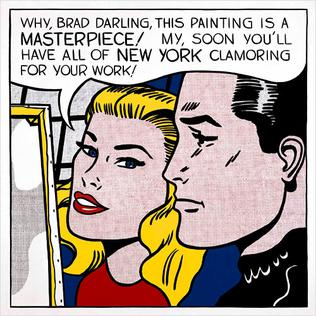

As a lover of contemporary art, I was intrigued by the McGill University Visual Art Collection’s array of large-scale tapestries. I walk by pieces like Roy Lichtenstein’s Modern Tapestry in the Arts building and Robert Motherwell’s Blue & Green in the McLennan Library every day. After watching the documentary Whaam! Blam! Roy Lichtenstein and the Art of Appropriation, I was inspired to find out if the design of this artwork, titled Modern Tapestry (Fig. 1) was appropriated.

McGill’s collection of tapestries were donated by alumna Regina Slatkin (B.A. ‘29) in the 1980s. They were sold by Modern Masters Tapestries Inc., a New York gallery that she ran with her husband that was active from 1965 to 1986 or 1987.1 Modern Tapestry was produced around the same time as Modern Poster (Fig. 2), which shares the same design but utilizes a smaller format and is a print. According to this research, I believe that Modern Tapestry is an original design.

This type of research is increasingly common as 2022 and 2023 have been exciting years in the art world due to the never-ending battles over intellectual property. Last year, the documentary Whaam! Blam! Roy Lichtenstein and the Art of Appropriation was released. Then, in May 2023, the United States Supreme Court Case Andy Warhol Foundation For The Visual Arts, Inc. v. Goldsmith Et Al. was affirmed.

All of this discussion revolves around the idea of fair use.2 To determine whether the use of an image or reproduction of an artwork under copyright is “fair,” there are four factors to be considered:

- The purpose and character of the use, including whether such use is of a commercial nature or is for nonprofit educational purposes;

- The nature of the copyrighted work;

- The amount and substantiality of the portion used in relation to the copyrighted work as a whole; and

- The effect of the use upon the potential market for or value of the copyrighted work.3

In effect, these factors are very subjective. How fair use is implemented changes from case to case.

To understand how this fickle legal jargon plays out in the art world recently, the Lichtenstein documentary is a good primer. Directed by James L. Hussey and Jesse Finley Reed, this documentary interviewed comic artists like Hy Eisman and Russ Heath on how their images were appropriated by Roy Lichtenstein for his high-selling art. For reference, ArtPrice ranks Roy Lichtenstein at 23rd of 100 best-selling artists ranked worldwide. His pieces frequently fetch millions, if not hundreds of thousands of dollars.4 His works are held in major collections like the Art Institute of Chicago, the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., and other museums worldwide. In 2017, Masterpiece (Fig. 3) was sold for $165 million.5 But, according to the documentary, Lichtenstein’s design was lifted from Ted Galindo’s work.

In the documentary, the original comic artists explain their plight. Take Hy Eisman for instance: a highly prolific comic artist, he has drawn for Popeye, Archie, The Munsters, and Tom and Jerry cartoons. While being a cartoonist can be highly rewarding, its compensation is not commensurate with passion nor experience. Eisman would produce five pages a day to get by. In the early 1960s, he was paid $1.66 per panel.

Cartoonist Russ Heath has a similar story. Around the same period, he worked for Marvel, which was then named Atlas. He made $75 a week in exchange for his drawings. After serving in World War II, he did not go to art school. Instead, he entered the field and learned how to draw on the job. Since he did not have access to live models, he took photographs of himself to use as a reference for his art.

Let’s compare the careers of Eisman and Heath to Lichtenstein’s. Lichtenstein did not get his big break until 1961 when he was nearly 40 with Look Mickey. He produced his most iconic and famous works between 1961 and 1964. At the time, little concern was shown for the comic artists whose works were being appropriated.

Next, there is the question of skill. While these comic artists spent decades dedicated to their craft out of pure passion, Roy Lichtenstein copied their designs. Using a projector to blow up the designs, Lichtenstein would trace them and change minor details. Then, he would use an aluminum screen and a roller to color the images. So, how much talent and skill does art like this really take? Does that even matter? Perhaps, Lichtenstein’s true message was that he was able to transform the low art of comics into the high art of large-scale paintings shown in galleries and museums. Nathan Dunne, author of Lichtenstein and staunch defender of the artist, says in the documentary “It’s not where you take it from, but where you take it to.”

According to Marc Greenberg, an experienced intellectual property lawyer, there is a reason why these artists can’t just simply sue. These comic artists were working for companies, like Russ Heath for Marvel. Therefore, they do not hold the copyright themselves, but the companies they worked for do. Because these artists do not hold copyright, they lack legal standing. In addition, these large companies feel it is pointless to sue because they might not make a profit after legal fees. Their priorities lie elsewhere. Furthermore, the estate of Roy Lichtenstein might be able to prove that his pieces were transformative in both intent and execution. Lichtenstein added new elements, changed colours, and changed the size of the original work all while aiming to display in expensive galleries and large institutions like museums. He also wasn’t reproducing them to put in a comic book, therefore changing the intent.

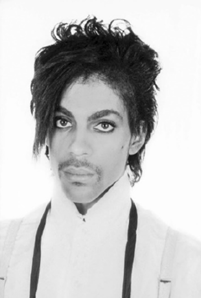

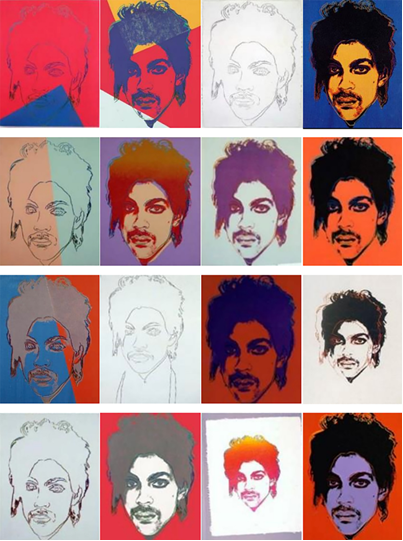

On the other hand, Andy Warhol has not been able to slide by so easily. Let’s set the scene. In 1984, Vanity Fair sought to license one of Lynn Goldsmith’s photographs of Prince to use as an “artist reference” (Fig. 4). The image would be used to accompany a story about the then up-and-coming musician. Lynn Goldsmith, who has made a career of photographing musicians, was paid $400 for the one time use of her photograph in the fashion magazine owned by media conglomerate Conde Nast. Vanity Fair hired Andy Warhol to produce a derivative work. But, he didn’t just stop at one piece. He made 16 in total (Fig. 5).6 For his pieces of celebrities, he zooms in on the subject’s face and reframes the image. This creates a disembodied effect that mimics a cinematic closeup. Next, he heightens the contrast and flattens the image on a sheet of clear acetate. He then uses that image to trace the outline on canvas and painted on top.7 A negative of the image would also be reproduced on a silkscreen so Warhol could pour art ink or paint onto the back side, then pull it through with a squeegee onto the canvas. Sections of the screen would be blocked off so Warhol could be precise with his placement of ink and paint.8 For his work published in 1984 by Vanity Fair, Warhol received an unspecified amount.9

Lynn Goldsmith did not know of this Orange Prince series until Prince’s death in 2016. In that year, the Andy Warhol Foundation was paid $10,000 so Conde Nast could license one of the works to run a story about the life and times of Prince Rogers Nelson.10 Upon learning of this, Goldsmith notified the Andy Warhol Foundation that she believed it had infringed her copyright. In response, the foundation sued Goldsmith for fair use.11 Goldsmith counterclaimed for infringement.12

With Supreme Court Justice Sonia Sotomayor leading the majority, Goldsmith’s case was affirmed in May 2023. This is where the four factors of fair use are important. First, the intent and purpose of the Warhol and Goldsmith pieces were deemed too similar. Both could have been used to illustrate a story about Prince. In addition, Sotomayor and the other justices in the majority did not consider the Warhol works to be transformative enough.

This recent case might open the door for more litigation concerning artists like Warhol. While it is unlikely the Lichtenstein estate will get sued, it might happen to other pop artists or artists that use source imagery in this manner.

Now, whenever you walk by the Lichtenstein tapestry in the Arts building, I invite you to think of the artists that Lichtenstein used as a foundation for his body of work. Modern Tapestry is currently on view in the Arts Building on the ground floor and is cared for by McGill’s Visual Arts Collection. (Editor’s Note: Modern Tapestry is temporarily in storage for a construction project, Summer 2024) To learn more about the public art on campus, contact us at vacollection.library@mcgill.ca to schedule a tour.

- To Vanessa Di Francesco (previous McGill VAC Assistant Curator) from Christine Dawson, e-mail, 25 April 2018, McGill University Visual Arts Collection Object File 1987-004. ↩︎

- Fair use is referred to as “fair dealing” in Canada. Because this article focuses on an American context, I will use the term “fair use.” ↩︎

- Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. v. Goldsmith (598 U.S. ___, 2023), 14. ↩︎

- ArtPrice by ArtMarket (Roy Lichtenstein (1923-1997); accessed November 1, 2023), https://www.artprice.com/artist/17505/roy-lichtenstein#. ↩︎

- $165 million is a lot of money! It was sold by Agnes Gund, president emerita of the Museum of Modern Art. With the proceeds from the sale, she created the Art for Justice Fund, which seeks criminal justice reform and a reduction of mass incarceration in the United States. I recommend Robin Pogrebin’s New York Times article “Agnes Gund Sells a Lichtenstein to Start Criminal Justice Fund,” https://www.nytimes.com/2017/06/11/arts/design/agnes-gund-sells-a-lichtenstein-to-start-criminal-justice-fund.html. ↩︎

- Warhol v. Goldsmith (598 U.S. ___, 2023), pg. 4 majority opinion. ↩︎

- Warhol v. Goldsmith (598 U.S. ___, 2023), pg. 5 of Kagan dissenting. ↩︎

- Warhol v. Goldsmith (598 U.S. ___, 2023), pg. 5-6 of Kagan dissenting. ↩︎

- Warhol v. Goldsmith (598 U.S. ___, 2023), pg. 4 majority opinion. ↩︎

- Warhol v. Goldsmith (598 U.S. ___, 2023), 2. ↩︎

- Warhol v. Goldsmith (598 U.S. ___, 2023), 5. ↩︎

- Warhol v. Goldsmith (598 U.S. ___, 2023), 2. ↩︎

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.