By Dr. Mary Hague-Yearl, History of Medicine Librarian, Osler Library of the History of Medicine

New at the Osler Library is a pair of books from 1775 that reflect concurrent advances in obstetrical knowledge in Europe and Japan. Kagawa Gen’etsu’s Shigenshi Sanron and Kagawa Genteki’s illustrated supplement to that work, Sanron Yoku, originated from the practical observations of Kagawa Gen’etsu, a self-educated Japanese obstetrician.

Gen’etsu is an interesting medical historical figure because his focus on observation and practical anatomy was in tune with a shift taking place within the Japanese medical profession, influenced by the transmission of Dutch knowledge. However, Gen’etsu’s adherence to practical observation stemmed in the first instance from his status as an autodidact. Having been denied a traditional education because of his humble background, his knowledge was informed by practice; it was later, after he had established the Kagawa School of Obstetrics, that he would have viewed (but not read) the influential illustrated works of Dutch physician Henrick van Deventer.[1]

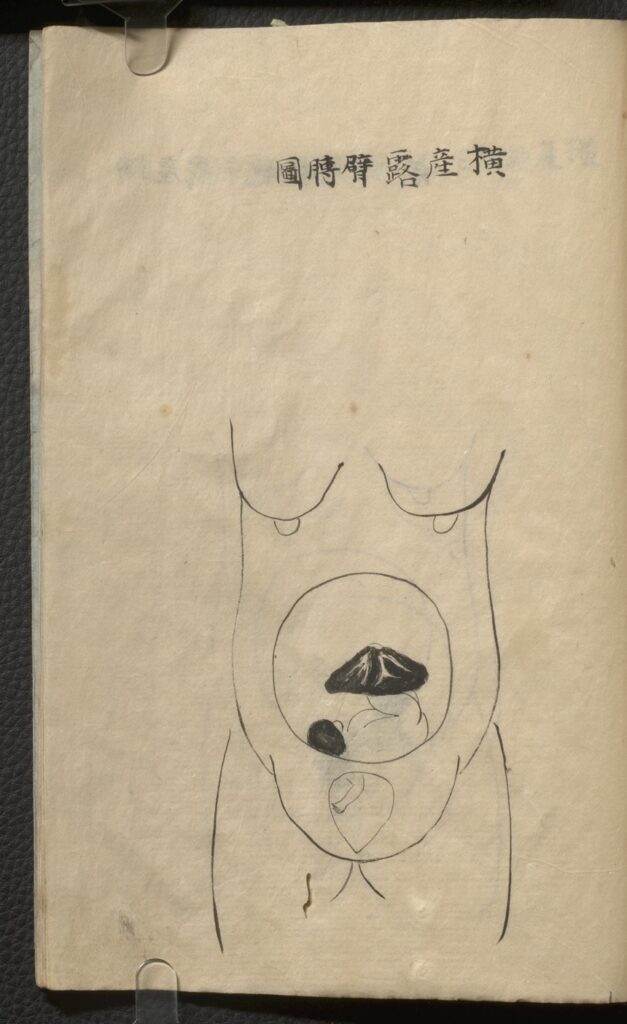

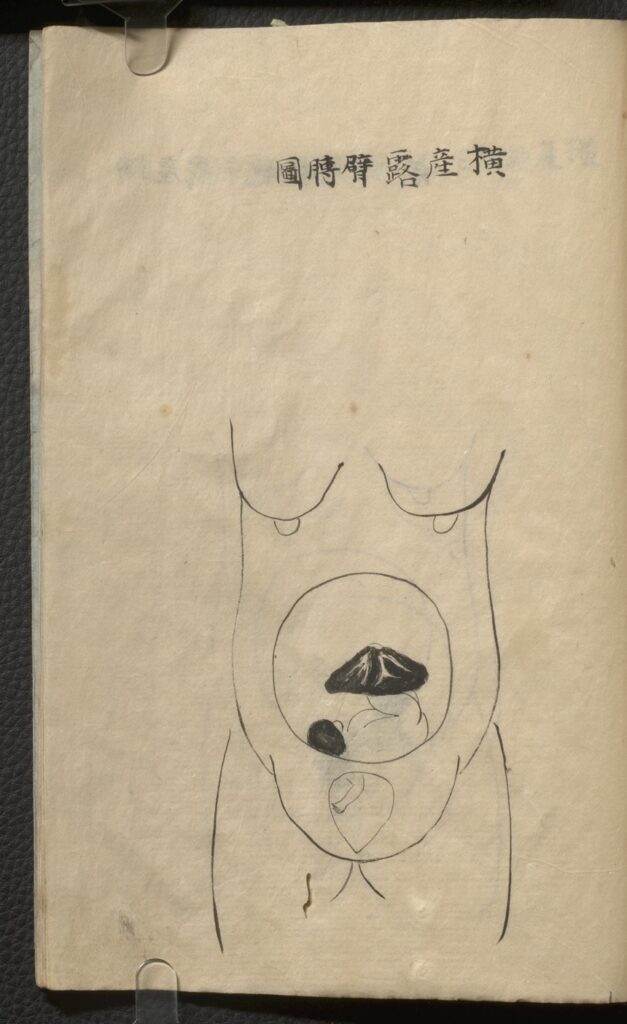

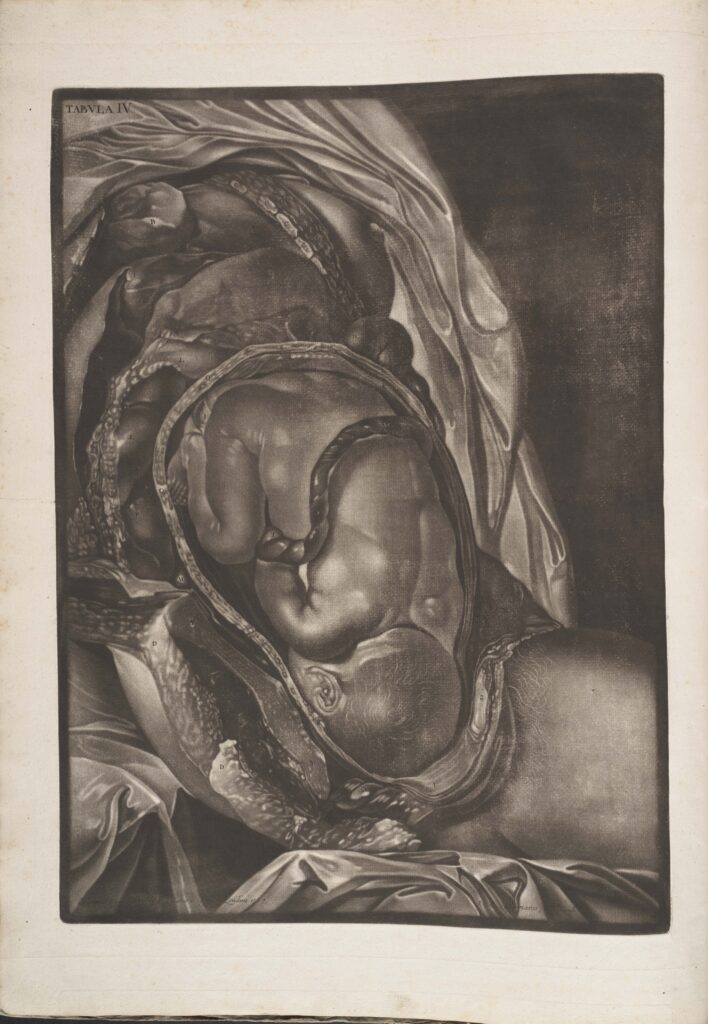

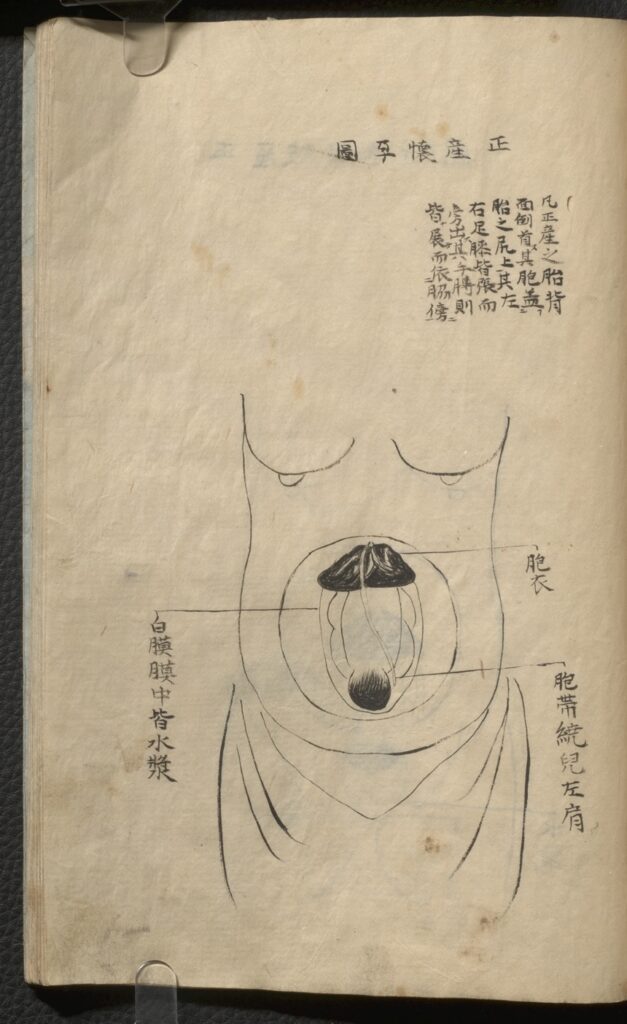

There are similarities between the illustrations in Genteki’s Sanron Yoku and the engravings in the obstetrical atlases of William Smellie (1754), Charles Jenty (1761), and William Hunter (1774), which appeared in Europe at the same time as Gen’etsu was developing his school in Japan. While Genteki’s works are found within quarto-sized volumes, the European works provided life-sized surrogates, described as “[s]tark, brutal, and fetishistically naturalistic.”[2]

These atlases presented newly-refined understandings of the anatomy of pregnancy, gained through dissection.

When Genteki provided an illustrated supplement to his master’s work, he would not have been aware of the giant obstetrical atlases emerging in Europe, yet they share characteristics that reflect the professionalization of obstetrics on both sides of the globe. Only the torso is shown, the rest of the body and thus any humanizing aspects cut off at the shoulders and just below the hips. As Yuki Terazawa has pointed out, it makes the pregnant female body a medical specimen; the woman is a passive and docile object in the medical procedure of childbirth.[3] Gen’etsu, like his educated European counterparts, argued for physician-assisted childbirth, though it should be noted that the Kagawa school did have practising female obstetricians. In this context, we can see that obstetrical treatises were not simply about anatomy. By highlighting the dangers of childbirth, the works highlighted here opened the door to the argument that pregnant women required the assistance of trained practitioners.

[1] Lyle Massey, “Pregnancy and Pathology: Picturing Childbirth in Eighteenth-Century Obstetric Atlases,” The Art Bulletin 87, no. 1 (2005): 73-91. Accessed March 25, 2021. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25067156. [this quote, p. 73]

[2] Yuki Terazawa, Knowledge, Power, and Women’s Reproductive Health in Japan, 1690—1945, Genders and Sexualities in History (Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan, 2018), https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-73084-4. See pp. 82-114 on Gen’etsu and the Kagawa School.

[3] Terazawa, pp. 89-94.

Traités illustrés d’obstétrique du XVIIIe siècle et la professionnalisation de la discipline en Europe et au Japon

Par Dr. Mary Hague-Yearl, Bibliothécaire de l’histoire de la Medicine, Bibliothèque Osler de l’histoire de la medicine

Nouveauté à la bibliothèque Osler : deux ouvrages datant de 1775 qui relatent les avancées simultanées des connaissances en obstétrique en Europe et au Japon. L’ouvrage de Kagawa Gen’etsu intitulé Shigenshi Sanron et son supplément illustré par Kagawa Genteki, Sanron Yoku, sont fondés sur les observations pratiques de Kagawa Gen’etsu, obstétricien japonais autodidacte.

Gen’etsu est une personnalité intéressante dans l’histoire de la médecine, car l’importance qu’il accordait à l’observation et à l’anatomie pratique était en phase avec le changement qui s’opérait au sein de la profession médicale au Japon, sous l’influence des connaissances transmises par les Hollandais. Cependant, dans le cas de Gen’etsu, le recours à l’observation pratique découlait d’abord de son statut d’autodidacte. Comme il n’a pas pu bénéficier d’une formation traditionnelle en raison de ses origines modestes, ses connaissances étaient fondées sur la pratique. Ce n’est que plus tard, après qu’il eut fondé l’École Kagawa d’obstétrique, qu’il a pu voir (parce qu’il ne pouvait pas les lire) les planches illustrées fondatrices du médecin hollandais Henrick van Deventer [1].

On note des similarités entre les illustrations du Sanron Yoku de Genteki et les gravures des atlas d’obstétrique de William Smellie (1754), Charles Jenty (1761) et William Hunter (1774), qui sont parus en Europe au moment où Gen’etsu mettait sur pied son école au Japon. Tandis que l’œuvre de Genteki est publiée au format in-quarto, les ouvrages européens présentent des illustrations en taille réelle, décrites comme étant « saisissantes, crues et d’une minutie obsessive »[2]. Ces atlas présentaient les connaissances nouvellement acquises sur l’anatomie de la grossesse, obtenues par dissection.

À l’époque où Genteki publie son supplément illustré en complément de l’œuvre de son maître, il ne peut pas connaître l’existence des atlas d’obstétrique géants qui voient le jour en Europe, et pourtant, tous les ouvrages de l’époque ont en commun des caractéristiques qui reflètent la professionnalisation simultanée de l’obstétrique sur deux continents. Seul le torse est illustré; le reste du corps, et donc tous les éléments qui confèrent son humanité au sujet, est coupé aux épaules et juste sous le bassin. Comme l’a souligné Yuki Terazawa, le corps de la femme enceinte devient ainsi un simple spécimen médical; la femme n’est qu’un objet passif et docile qui subit l’intervention médicale qu’est devenu l’accouchement [3]. Gen’etsu, comme ses homologues européens instruits, était en faveur de l’accouchement assisté par un médecin; il importe toutefois de souligner que l’école de Kagawa comptait aussi des obstétriciennes praticiennes. Si l’on tient compte de ce contexte, on constate que les traités d’obstétriques n’avaient pas seulement pour but de présenter l’anatomie. En faisant ressortir les dangers de l’accouchement, les ouvrages présentés ici ont ouvert la voie à l’argument selon lequel les femmes enceintes ont besoin de l’assistance de praticiens qualifiés.

[1] Yuki Terazawa, Knowledge, Power, and Women’s Reproductive Health in Japan, 1690—1945, Genders and Sexualities in History (Cham, Suisse : Palgrave Macmillan, 2018), https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-73084-4. Voir les pages 82 à 114 sur Gen’etsu et l’école Kagawa.

[2] Lyle Massey, “Pregnancy and Pathology: Picturing Childbirth in Eighteenth-Century Obstetric Atlases,” The Art Bulletin 87, no. 1 (2005): 73-91. Consulté le 25 mars 2021. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25067156. [p. 73]

[3] Terazawa, pp. 89-94.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.