By Christopher Lyons, Head Librarian, Rare Books and Special Collections

I love attending antiquarian book fairs. There is nothing like seeing rare books in the flesh.1 Imagine my surprise when a book dealer picked up a book and did something one never does; he pressed his thumb on the right side of the book (the fore-edge) and curled the leaves upwards.

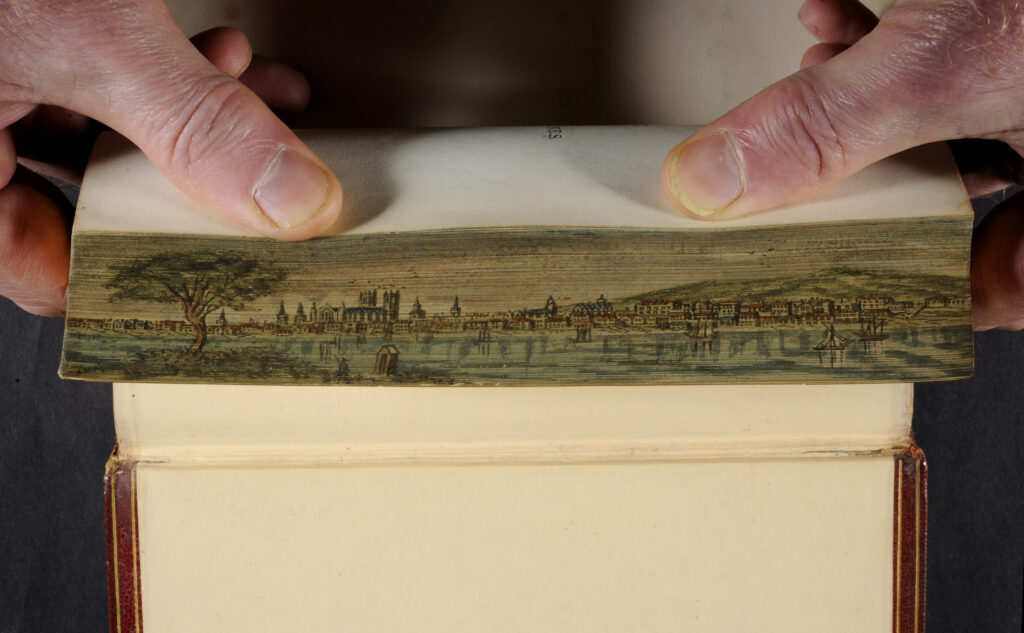

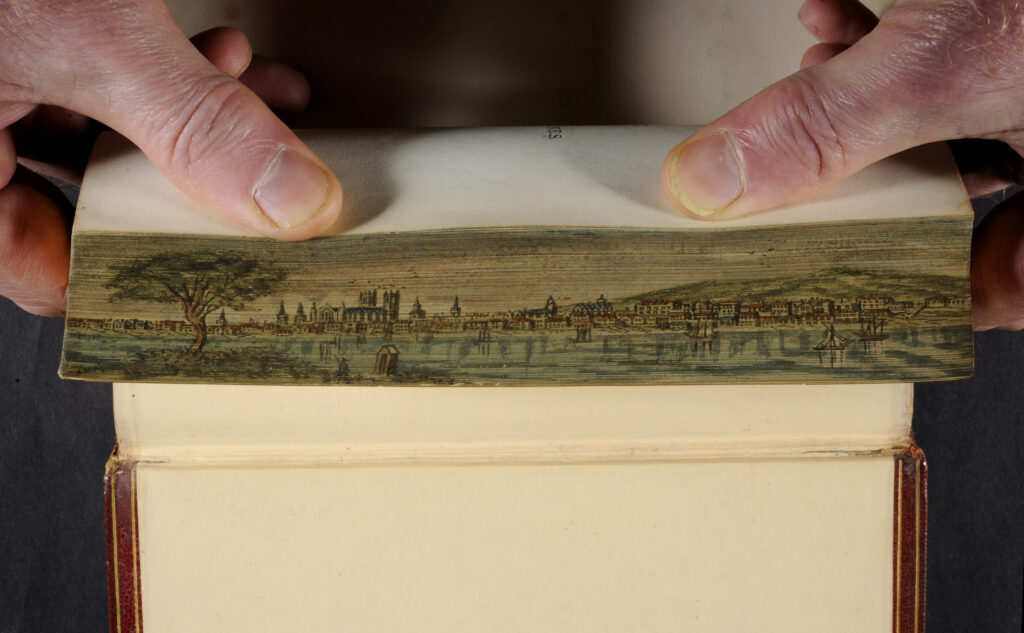

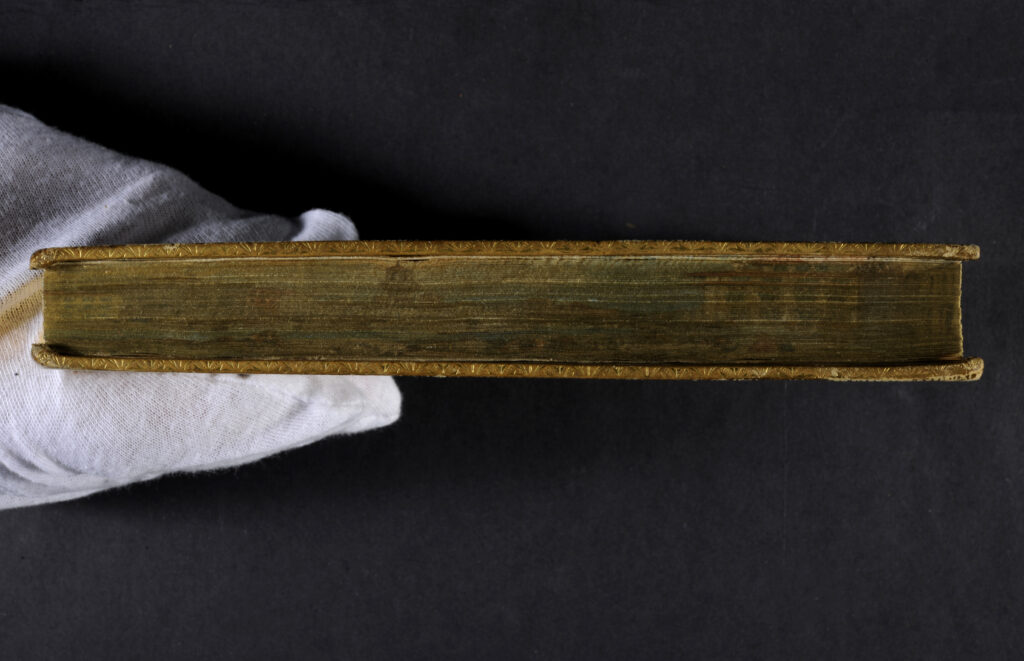

This bookseller’s sleight of hand was a demonstration of the art of fore-edge painting. Fore-edge painting can mean two things: first, the application of colour to the paper edges of a book, often in gold, but sometimes in red, blue, green, or marbling. Here I focus on the second meaning: the painting of watercolour images that are invisible until one fans the fore-edge of a book. Fore-edge painting is delicate work. The artist places the interior of the book (excluding the boards) into a press that holds the ends of the leaves fanned out at about a thirty-degree angle. The artist then paints on the sloped surface.2 The actual tips of the leaves should be gilded or coloured so that the image remains invisible when the book is either closed or handled normally. It is only when the edge is fanned that the painting magically appears.

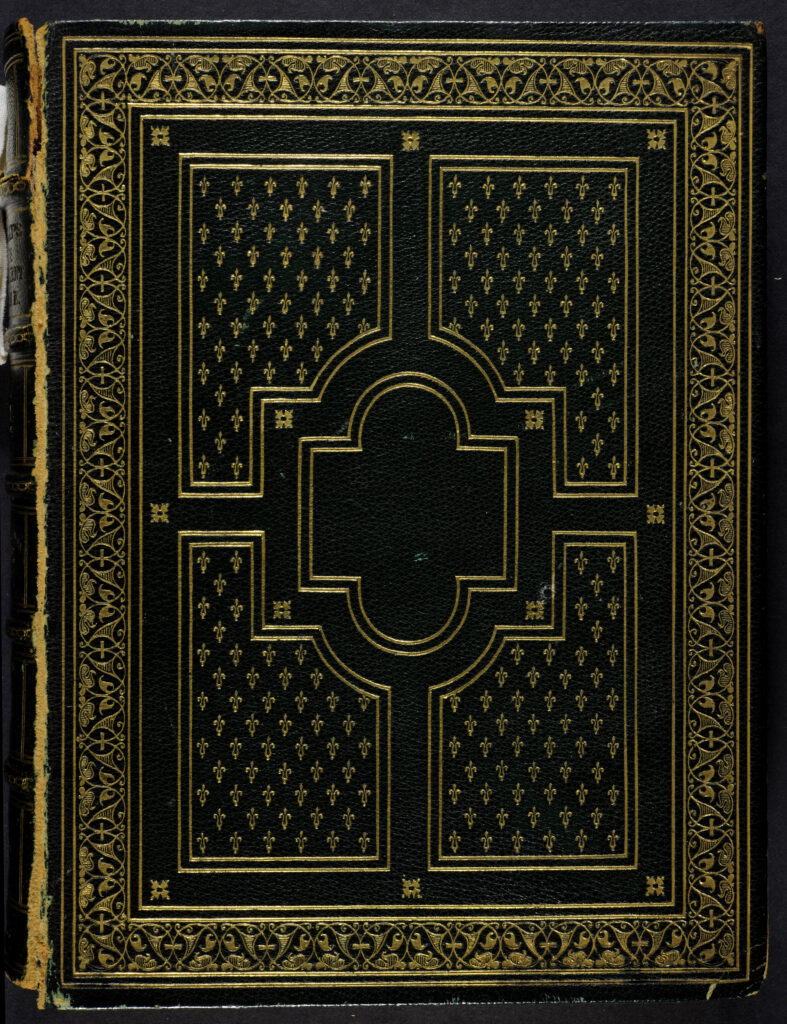

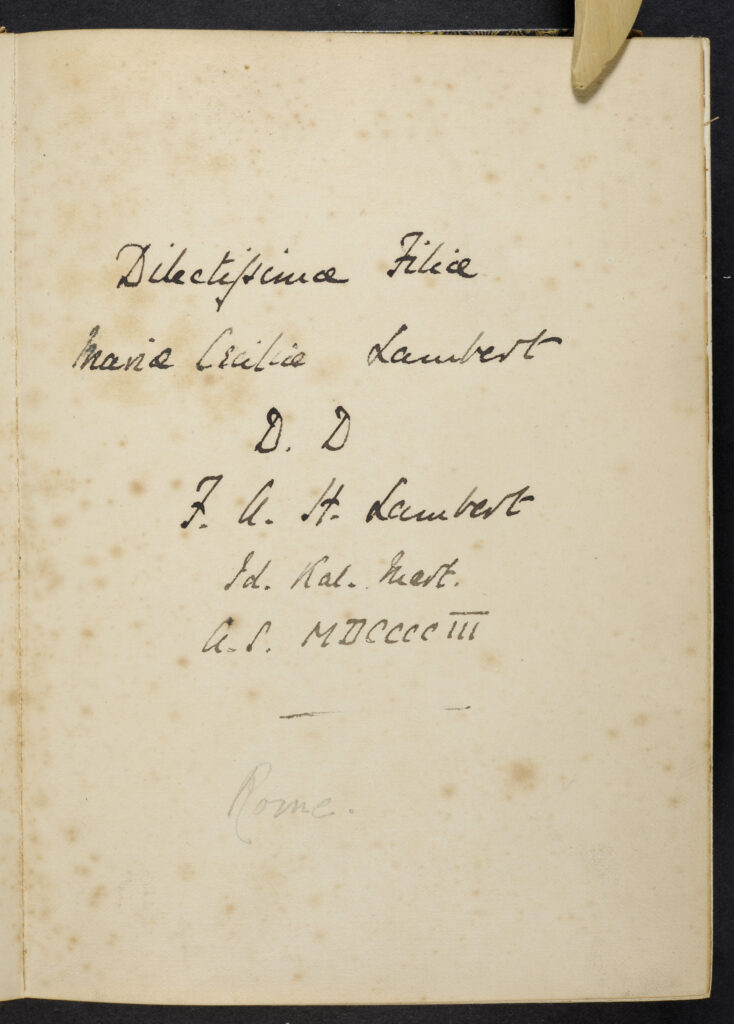

Fore-edge painting is primarily a British practice which dates to the 17th century. I examined some examples of the art in the McGill collection. The first is Thomas Babington Macaulay’s Lays of Ancient Rome, (circa 1870) (pictured below). Produced by renowned London bindery Riviere, it features a landscape painting and gilt fore-edge. We can only speculate if Riviere commissioned the fore-edge painting. The book was originally given to a student at Eton by his tutor, and later passed on to the recipient’s daughter. McGill’s Redpath Library purchased the book in May 1934 from English antiquarian dealer George Herbert Last, who sold antiquarian books to many major libraries worldwide. The library paid £3, 3 shillings for the book, significantly more than anything else purchased at that time. Bought for the library’s rare collection, one can assume that the vanishing fore-edge painting was the major attraction for purchasing this otherwise common title.

The library acquired another example from a Toronto dealer in 2019. The Hymnal Companion to the Book of Common Prayer (London, 1870) is inscribed by the author, the Vicar of Christ Church in Hampstead, to his daughter. What made me snap this up is that there is a double fore-edge painting! Fan the edge one way and there is a view of Quebec from the St Lawrence River. Fan it the other way and the scene is the Montreal waterfront! The images both appear to date from the same era as the book. The mystery here is that there is no evidence that the owner of the book, Emily Rosa Birckersteth, ever came to Canada. She married Frank Montagu Rundall, who spent his entire professional life with the military in British India and then retired in Britain. There seems to be no way to determine when the book came to Canada and who painted those scenes.

Although fore-edge paintings are easy to reveal once you know the trick, uncovering their creators is a much greater conundrum, well worth a second look.

[1] Maybe “in the binding” is more accurate. On the other hand, books are often bound in leather and other animal skins, so maybe flesh is okay after all. Never mind!

[2] For a good explanation of the techniques, complete with videos, visit the website of fore-edge artist Martin Frost at www.foredgefrost.co.uk.

Dissimulées à la vue de tous : les tranches peintes des Livres rares et des collections spéciales

Par Christopher Lyons, bibliothécaire en chef, Livres rares et collections spéciales

J’adore les foires du livre ancien. Rien de tel que de tomber sur des livres rares en chair et en os[1]. Imaginez quelle ne fut pas ma surprise quand un marchand de livres a cueilli un ouvrage pour agir comme personne d’autre ne fait; il a pressé son pouce dans la partie droite du livre (la tranche de gouttière) pour retrousser les feuillets vers le haut.

Le tour de passe-passe du marchand illustre l’art de la peinture sur gouttière qui peut prendre les deux formes suivantes : d’abord, l’application de couleur sur les bordures de page, souvent or, mais parfois rouge, bleu, vert ou en jaspage. Passons maintenant à la seconde définition : l’application d’aquarelles qui n’apparaissent que lorsque la gouttière du livre est disposée en éventail. La peinture sur gouttière est un travail délicat. L’artiste place l’intérieur du livre (exception faite des ais) dans une presse où les feuilles sont disposées pour former un éventail en angle d’environ trente degrés. Ensuite, il peint la surface courbée[2]. Les bordures doivent être dorées ou colorées, de sorte que l’image reste invisible quand le livre est fermé ou utilisé normalement. Ce n’est que lorsque la bordure est disposée en éventail que la peinture apparaît comme par magie.

La peinture sur gouttière est une pratique, surtout britannique, qui remonte au XVIIe siècle. J’ai examiné quelques exemples de cette discipline artistique dans la collection de l’Université McGill. La première, Lays of Ancient Rome, (vers 1870) est l’œuvre de Thomas Babington Macaulay. Produite par le réputé atelier de reliure londonien Riviere, elle représente un paysage et une gouttière dorée. Nous pouvons imaginer qu’il s’agit d’une commande de cet atelier. Au départ, ce livre est le cadeau d’un tuteur à son étudiant à Eton, transmis ensuite à la fille de cet étudiant. La Bibliothèque Redpath de McGill l’a acquis en mai 1934 de l’antiquaire anglais George Herbert Last, fournisseur de nombre de grandes bibliothèques autour du globe. La bibliothèque a déboursé trois livres et trois shillings, ce qui est supérieur, et de beaucoup, au coût de tout autre achat à l’époque. Étant donné que l’ouvrage était destiné à la collection des livres rares de la Bibliothèque, on peut supposer que sa peinture sur gouttière en éventail représentait le principal attrait de ce titre par ailleurs plutôt courant.

En 2019, la Bibliothèque acquiert un autre exemple d’un marchand torontois : The Hymnal Companion to the Book of Common Prayer (Londres, 1870) que l’auteur, le vicaire de la Christ Church d’Hampstead, a dédié à sa fille. Ce qui m’a allumé, c’est que la gouttière comprend deux œuvres! Si on dispose le livre en éventail, d’un côté, on trouve une vue de Québec à partir du Saint-Laurent. De l’autre, c’est le front d’eau de Montréal! Ces deux peintures semblent correspondre à l’époque de la publication du livre. Dans ce cas, ce qui intrigue, c’est qu’il n’existe aucune preuve selon laquelle la propriétaire du livre, Emily Rosa Birckersteth, ait jamais mis le pied au Canada. Elle a marié Frank Montagu Rundall, qui a passé l’ensemble de sa carrière dans les forces armées de l’Inde britannique avant de prendre sa retraite en Grande-Bretagne. Il semble impossible de déterminer le moment de l’arrivée de ce livre au pays ni l’identité de l’auteur de ces scènes..

S’il est facile de dévoiler les peintures sur gouttières quand on sait s’y prendre, il est beaucoup plus malaisé d’identifier leurs créateurs, et cela justifie bien d’y regarder à deux fois.

[1] En fait, il serait plus exact d’écrire « dûment relié ». Cela dit, il arrive souvent les reliures soient fabriquées avec du cuir et d’autres peaux d’origine animale, on peut peut-être parler de chair malgré tour. Bon, d’accord!

[2] Pour obtenir un bon exposé des techniques, accompagné de vidéos, visitez le site Web du décorateur de tranches Martin Frost, au www.foredgefrost.co.uk.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.