Summer is the perfect time for a holiday get-away. Maybe you are in the midst of looking into various guides and maps to get to your perfect destination and make the most of it. Travellers of the nineteenth century did much of the same. With the aid of travel guidebooks, they found their way to some of Canada’s most refreshing and enchanting places, right here in Quebec.

Guidebooks took root in North America over 200 years ago, in the 1820s. Travel back in the day was achieved in group tours by a combination of steamer, river boats, canal boats[1], stage coach and rail. The “Northern tours” were the latest trend, offering a string of attractions that brought American travellers from New York City up the Hudson River to Albany with a stop-over in Saratoga or Ballston Springs. Travellers continued with a westward trip by way of the Erie Canal to Niagara Falls, with a return trip by a longer, more adventurous trip through Canada, via Lake Ontario and the Saint Lawrence River, with an excursion up to Quebec City.[2]

The first series of guidebooks in North America

The earliest guidebook printed in North America was entitled: The Fashionable Tour: An excursion to the Springs, Niagara, Quebec and Boston (1822). It emerged from Saratoga Springs, a central resort built around mineral springs, printed by Gideon Davison, who was Saratoga’s printer. This guidebook was updated and re-issued over a number of years, a key means of increasing the visibility of Saratoga Springs and surrounding vicinity.

Travel to northern sites had its merits, as it still does today – an escape from the oppressive heat of summer and a way to benefit from the healthy clean and brisk air. Accessible by water routes in the summer months when waterways were free of ice, magnificent Quebec City was a prime destination integrated into the northern tours, which gave rise to the first guidebook produced in Lower Canada.

The first Canadian guidebook

The Picture of Quebec (1829) was intended to serve an influx of American visitors. It was written by an American congregational minister who had settled in Quebec, George Bourne. In the “Notice” to the readers, Bourne states his purpose: “Long has it been a just complaint that unexpected difficulties are realized by strangers in exploring the curiosities of the far-famed Canadian fortress and its vicinity.”

This little pocket book was well thought out. The most important engraver working in Quebec at the time, James Smillie, was hired to produce the charming plates of illustrations which he sent to New York City for printing “because of the absence of both a good copperplate press and a printer in Lower Canada.”[3] He also located a map maker and printer in New York to make the delicate folding map of the “City of Quebec.” The text portion was printed in Montreal by Robert Armour, wholesale bookseller, stationer, and printer. His firm grew in succeeding years by producing almanacs, maps, city directories, and more guides.

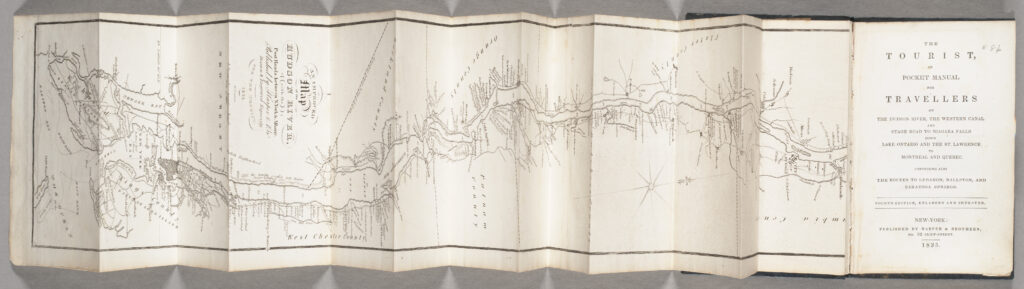

By the 1830s, a Canadian itinerary to both Quebec City and Montreal was included in Vanderwater’s Pocket Manuel for Travellers. Published out of New York, the itinerary of the 5th edition (1836) included a voyage up the Hudson River, routes to Lebanon, Ballston, and Saratoga Springs, a western canal and stage road to Niagara Falls, and a return trip down Lake Ontario and the St. Lawrence to Montreal and Quebec. The outstanding feature of this guidebook is a folding panoramic plan of the Hudson River, which opens in accordion style horizontally. So impressive was the map that a few years later, the Hunter Guidebook series, offered a similar, albeit very fragile, folding panorama of a trip on the St. Lawrence all the way through to Niagara Falls. (see this edition in the video above.)

The first pan-Canadian guidebook

The 1840s witnessed the unification of the Canadas into one Province of Canada. This leads us to the Canadian Guide Book (1849) printed in Montreal by Armour & Ramsay. This Canadian guide symbolically celebrated the formation of Canada, including the provinces of Ontario, Quebec, and the Maritimes. It also presents an extraordinary “Map of Canada” (1848), drafted by Edward Staveley, a civil engineer in Montreal. The map was outsourced for engraving to Edinburgh by W.& A.K. Johnston, Geographers and Engravers of the Queen. An earlier version of the map appeared in 1844. For the guidebook, tourist place names were added, such as Lake Magog, and it showed the outlines of railroad and canal routes, such as the Lachine Canal and track lines leaving the south shore towards the Richelieu River.

As time progressed, serial guidebooks were jam-packed with information, and meticulously organised, offering distance charts, along with tariffs and time-tables for various modes of travel. They included practical information on exchange rates, and custom procedures, and various bits of advice, such as the appropriate clothing for particular regions. Maps were still a major commercial feature of the early guidebooks, now accompanied by precise tours, routes maps, city plans, in-text illustrations of primary sites and monuments, advertisements, publisher’s catalogues, and space for traveller’s memoranda. These books sometimes carry a former owner’s signature, and various markings in pen, bringing us into a traveller’s personal journey. Just imagine if the little pocket book was carried on a walking tour through Quebec City, or at the Falls.

Canada enters the popular Baedeker series

Our final example regards the enterprise of Baedeker guidebooks. Karl Baedeker of Germany started publishing serial guidebooks in the early 1830s for a European audience. Later in the century, these guides covered a choice of places around the world. It was not until 1894 that Baedeker launches a volume on Canada. The first edition of Baedeker in Canada was bound in the iconic red cloth binding with marbled edges entitled: Dominion of Canada with Newfoundland and an Excursion to Alaska. Canada in part was still largely uncharted territory. Baedeker, as editor, takes the time to explain in the preface that he fears the “inevitable imperfections” in the guidebook due to “the vast extent of the Dominion of Canada”. Rare Books also holds the companion volume on the United States, published a year earlier, in 1893, which is twice the size in terms of text and illustration. A writer from Scotland was hired to do both volumes, James Fullarton Muirhead, based on his personal travels, justifying further the editor’s concerns for accuracy. Baedekers would soon be competing with many specialized American publishers, like Appleton’s, to gain a share of the lucrative tourist industry.

These few highlights give a sense of a burgeoning tourist industry on our continent and how a handful of printers were crucial to its success. They opened the way for a major speciality market of guidebooks publishing.

We welcome you to step back in time to look up one or two of your favourite vacation spots in the myriad of Canadian and American historical guidebooks safely packed away in Rare Books and Special Collection. Until then, bon voyage!

[1] The Erie Canal opened in 1825. Canal boats were sometimes drawn by mules. Motorized barges only began to be used in the next century.

[2] See Brown, Dona, Inventing New England :Regional Tourism in the Nineteenth Century, Washington: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1995, p. 24.

[3] See Joan Winearls, “Illustrations for Books and Periodicals”, in History of the Book in Canada, vol. 1, p.103-109.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.