The Gwillim Project centres around the lives of two English sisters in early 19th c. Madras (now Chennai): Elizabeth Gwillim (1763-1807) and Mary Symonds (b. 1772). Both sisters were avid artists and dedicated letter-writers; their paintings of flora, fauna, and landscapes alongside their rich correspondence offer us a glimpse into the social networks, visual cultures, and natural ecologies of early-1800s India and England.

Saraphina Masters is a recent MA graduate of the Art History and Communications Studies department, where Hana Nikcevic is a current MA student. Both joined the Gwillim Project in June as visual research assistants. Their accounts below discuss the research they recently presented for Gwillim Online, the project’s webinar series. Their presentations, along with the other webinars, can be viewed on the Gwillim Project’s YouTube channel.

Saraphina:

After graduating in the spring and leaving Montreal in the summer, the Gwillim Project has been a wonderful way for me to stay connected to both the McGill community and to the discipline of art history. I earned my Master’s degree writing a thesis about a female artist of the late eighteenth century (albeit an oil painter, Angelica Kauffman) so the topic of the Gwillim-Symonds sisters drew me in right away.

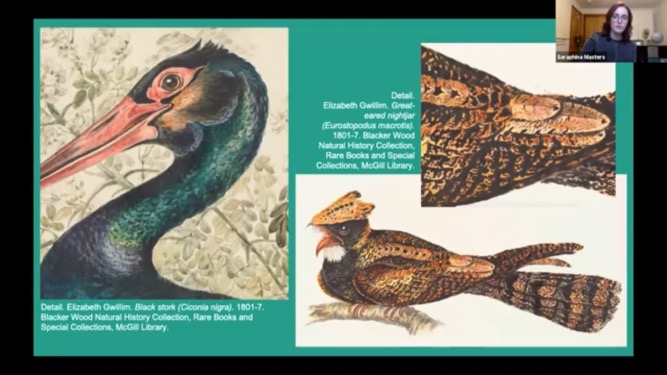

My work began by reading the six years worth of letters written by Elizabeth Gwillim, familiarizing myself with her life and her personality. This, accompanied by background research into the world of British colonists in South India in the first decade of the nineteenth century, set me up to study her paintings in a well-informed manner. These paintings are held in the Blacker-Wood collection and are available to view in high resolution on the Archival Collections Catalogue website here.

I then endeavored to create a style guide for Gwillim’s works, the abridged results of which I presented on November 17th in the Gwillim Project’s webinar series.

Since there exists a great deal of variation within the 121 extant paintings of birds, I ended up with less of a precise style guide, and more a curated set of characteristic attributes against which one could compare a potential Gwillim. This became my mode of thinking because we know that Gwillim painted approximately 200 works, but the Blacker-Wood Library only possesses about 60% of her possible corpus. The idea of Gwillim’s birds existing elsewhere in the world brought me to a type of style guide that could perhaps one day help to attribute new or lost works. My guide is by no means exhaustive and remains a work in progress as I spend more time with the paintings and immerse myself further in Gwillim’s world.

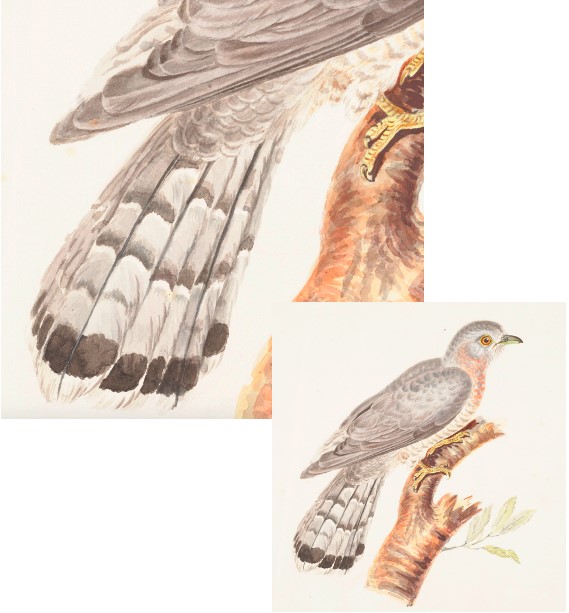

The style guide begins with a review of common background features of the bird paintings, such as palm trees and architecture. I then focus considerable attention on her depictions of the birds themselves, particularly their feathers. It seems that Gwillim was somewhat of an early expert on illustrating pterylography, “the descriptive science of plumage and the arrangement of the feather tracts on the bird’s skin.” This is visible in her extremely fine renderings of the feathers and their exact placements on the bird’s body (see the example below). My understanding and interpretation of this aspect of Gwillim’s work has been informed by my continuing study of previous depictions of birds, as there is a rich tradition of ornithological illustrations into which Gwillim’s work fits and from which she diverges.

As I continue working with the Gwillim Project in the new year and term, I am looking forward to continuing my research on the representation of natural history at the turn of the nineteenth century and how women participated in this growing field as both artists and scientists.

Hana:

As a student of contemporary ecological art, what initially drew me to the Gwillim Project was an interest in representations of natural history, work at the intersection of science and art, and women’s historical involvement in both of these areas. In my main research, I deal with artists’ present-day responses to climate crisis and ecological loss; as such, taking part in the Gwillim Project’s investigation into past centuries’ illustrations of natural environments seemed like it would offer the crucial historical background to my own work.

Contrary to my expectations, though, my recent research has led me away from ecology and towards eighteenth- and nineteenth-century optical devices. While Saraphina explores Elizabeth Gwillim’s work, my objective is to look into the work of Elizabeth’s sister, Mary Symonds, who accompanied Elizabeth and her husband Henry Gwillim on their move to Madras, India, in 1801. Younger than Elizabeth and self-avowedly in pursuit of a husband (she found one!), Mary was also a dedicated artist in Madras. She tried her hand at portrait miniatures, natural history painting, and local landscapes.

Mary’s watercolour landscapes are preserved in the “Madras and Environs Album” at The South Asia Collection, Norwich. Amongst these watercolours are four street scenes, each of which depicts a row of Indian individuals and assemblages. These street scenes are fascinating not only because they give us a glimpse into how a Madras street may have looked in the early nineteenth century, but also because they show us that Mary was experimenting with some particularly interesting modes of depiction. One of the rows of people is cut out (almost like a row of paper dolls), and Mary tells us in a letter what she had in mind: “I intended to make a great many more, & to fix them in a box, to represent a street… this method I invented to give you [her sister in England] some idea of the population of this country, [as] they would then be about as thick, as the people are here in the streets.”

Evidently, then, Mary planned to make a little three-dimensional model, creating the effect of a crowded street by layering paper images. I was delighted by this, and I set about trying to locate her potential inspirations. Mary claimed to have “invented” the method––could that be true?

As I discovered, perspective views––more commonly known as “peepshows”––were all the rage in England in the nineteenth century, and they distinctly resemble Mary’s intended 3D model. Paper peepshows, however, didn’t surface in England until around 1820. Toy paper theatres––also very similar to Mary’s work––were popular, too, but the first English toy theatre (or “juvenile drama”) popped up around 1811. Mary, meanwhile, made her ‘perspective view’ in 1803! What else, then, could she have seen? Searching through eighteenth-century visual culture, I came across Martin Engelbrecht’s perspective views; the layered stage sets of the Georgian theatre; artist Philip James de Loutherbourg’s mini-theatre-of-nature, the Eidophusikon; travelling peepshow men (who carted around perspective views in boxes to events like fairs); and painted transparencies (translucent, backlit paintings, sometimes made by layering and cutting out paper). There was a wealth of precedents Mary could have drawn on, but she was nonetheless remarkably creative to have thought to deploy such a method in her own work.

It’s been wonderful to learn more about Mary’s visual world, and my next area of inquiry into her artwork is more aligned with my initial expectations. When Casey A. Wood stumbled upon Elizabeth’s stunning bird paintings at a London art dealer’s shop in 1924, he also acquired a small portfolio of thirty watercolours of Indian fish. Although Wood wrote that the fish were signed “E.G.,” the Gwillim correspondence reveals that it was actually Mary who occupied herself with painting fish. I’m now hoping to learn more about how these fish were painted, where they fit in the context of both ichthyological illustration and women’s watercolours, and what the origin and significance are of the inscriptions––potentially in Urdu––on the paintings.

Made by author using reproductions of Mary Symonds’s watercolours, 1803, South Asia Collection, Norwich.

Want to learn more? Email ladygwillim@gmail.com to sign up for a newsletter from the project.

By Saraphina Masters and Hana Nikcevic, visual research assistants

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.