By Nikolas Lamarre

Nothing says Romanticism more than the inevitable connection between a man and his love for flowers: Nature’s very own living souls.

McGill University Archives, MG1022, c.21, “Illustrations de Biography”, John William Dawson, pp.5, 9 and 43.

“To the Myrtle”:

Sweet emblem of all that is loving and true,

Fair child of the seasons who all claim their due;

May the Springtime of life give fair promise like thine

That our manhood with honour and virtue may shine

(McGill University Archives, ‘To the Myrtle’, MG3044, c.1, “Album of Sketches”, p.39)

McGill University Archives, MG3044, c.1, “Album of Sketches”, Eliza and Charlotte Mountain, pp. 2, 138, 149.

Let me introduce you…

This poem from the Mountain Family fonds is offering a taste of British Romanticism at its finest to the likes of Wordsworth and Coleridge’s Lyrical Ballads. In the peak of the Romantic Age, it was encouraged for young men to go forth and discover the depth of their character by grounding themselves in Nature, which mostly involved quite a fair amount of brooding reflections on life. Nothing more to expect when one ‘wanders lonely as a cloud’. Artists were then aware that “there [was] a feeling in the heart of man, above fancy’s power that [could not] be perceived by outward sense; Nor taught by imitative arts pretense. When faced with this transcendental Nature, the sublime power [was] felt and known and measured in its inward growth alone (McGill University Archives, “Family Poems”, MG3044, c.1, p.46). One could only hope for the spark of genius which would properly encapsulate the grandeur of their surroundings.

Similarly, in the era of exploration in a pre-confederation Canada, men of these times would keep thorough records of their journeys either through notebooks, diaries, letters, or even scrapbooks. One of these pioneering figures, both documenting the country’s evolution as a geologist, and supervising the expansion of McGill University as an educator and principal, is John William Dawson (1820-1899) who looks exactly like any proper mid-Victorian you will encounter: a strong faced and bearded man with a concerned look in his eye. Nothing less for a burgeoning scientist constantly at odds with an equally flourishing Charles Darwin.

With a career spanning over the latter half of the nineteenth century, William Dawson, as his family called him, helped introduce some of the key threads of McGill’s fabric such as the education of women, the Redpath Museum and Library, the Normal School (now the Faculty of Education), and much more. No wonder the Dawson-Harington Family Papers was probably the most requested fonds this Summer, being one of the biggest (over a hundred containers!) and most well detailed, it does not surprise me that it sparks interest in many.

The Dawsons’ tender side

The careful archiving of this extensive collection really makes one rethink about writing single-lettered text messages in the future… Amongst the numerous correspondence of Principal Dawson is hidden his most personal possessions; most notably a collection of various sketches, drawings, and watercolours. One timeless item is kept inside his “Illustrations de Biography”: a piece of Lady Dawson’s wedding veil jauni par le temps. It is hard to tell if it was put together post-mortem by his relatives, or if he kept it himself for some time, though it does not take away from the particular attention that went into its production.

Though Principal Dawson did not necessarily write poetry in his spare time, his son did. Here is an excerpt from George Mercer Dawson’s time in the McGill Literary Club:

McGill University Archives, MG1022, c.21, “Illustrations de Biography”, John William Dawson (top) and Unknown print (bottom) pp. 15, 87.

“A group of poets!!! Hard at work

Who ‘cool the air with sighs’

Searching for rhymes that will not come

For thoughts that will not rise. […]

Our eyes with ‘frenzy fire’ may roll

But not poetic fire

Our hair in all confusion fall

And still no muse inspire […]”

(McGill University Archives, MG1022, c.56, f.17)

A nice nod to Shakespeare’s The Tempest as this tongue-in-cheek ballad aligns with his father’s own lighthearted nature. A stark contrast to the rest of his less than optimistic poetry—surely these were hard times.

Speaking of another George, from another time

George Jehoshaphat Mountain (1789-1863) has a familiar face reminiscing of a young poet, or a philosophe with his feathery hair and doctorate in Divinity. One that I cannot quite put my finger on…neither did everyone I asked. Et pourtant, as the first Principal of McGill College—for a mere nine years— Bishop Mountain oversaw its concrete establishment as an institute of higher education though not without its fair share of trials and tribulations regarding the future of James McGill’s controversial estate. The typical outcome when family and money are mixed together. He then went on to establish Bishop University as well and became first archdeacon of Quebec (or Lower Canada back then). As Mountain’s mighty legacy is partly held in the official records of McGill University, his more ‘private’ belongings are contained within one small box housing only two items: his daughters’ album of watercolours and sketches (1825-1851) and a manuscript book of ‘Family Poems’, which most were penned by himself as he was also a poet à ses heures.

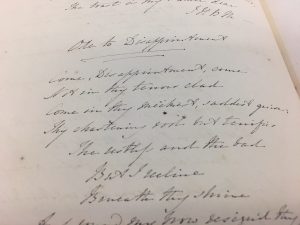

“Ode to Disappointment”

Come, Disappointment, Come

Not in thy tenor clad

Come in thy […] saddest guise…

“Lift your veil of familiarity/Show your true nature” definitely should have been the follow-up.

Of course there ought to be, in a collection of poems, at least one personification of powerful feelings (as he is lamenting his state of being in this one) recollected in tranquility (as many were also composed at sea…)

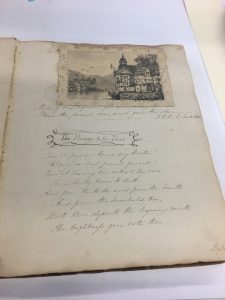

“The Message to the Dead”

Thou’st passing hence my Brother!

Oh! My earliest friend farewell!

Thou’st leaving me without thy voice

In a lonely home to dwell:

And from the hills and from the hearth

And from the household thee,

With thee departs the lingering mirth

The brightness goes with thee.

…

Ah, isn’t this “the way of the soul”?

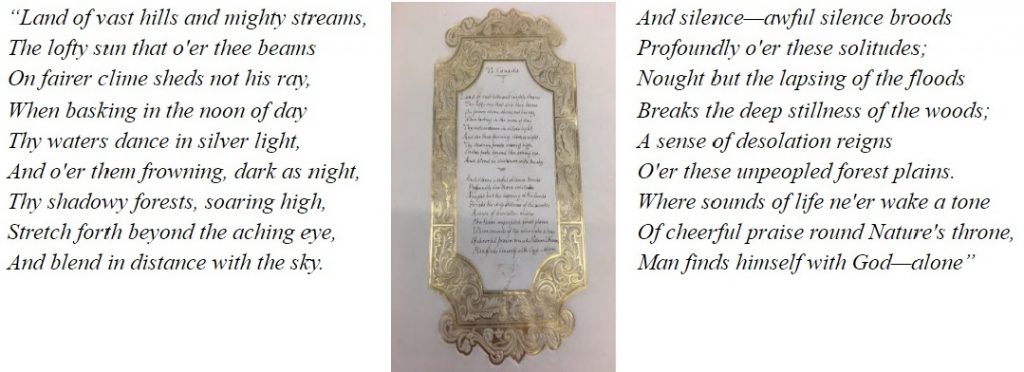

Nowhere Lands

Most of Bishop Mountain’s works are tightly related to the beauty of the Canadian landscape, as well his daughters’. Their sketchbook is even introduced by Susanna Moodie’s “Ode to Canada” from her Roughing It in The Bush: or, Forest Life in Canada (1852).

McGill University Archives, Top Left/Right: MG3044, c.1, “Album of Sketches”, Sophia Simcoe (copy) pp.15,20,32, 99, 137. Bottom Left/Right: MG1022, c.21, John William Dawson, p.20, 71.

These verses very much encapsulate the essence of the sketches found both in the Mountain and Dawson sketchbooks. With the multiplicity of social scenes in the midst of the long nineteenth century, this envy for nowhere lands free of civilization–though gravely fallacious–is a recurrent trope in Romantic landscape art. Canada acted as a lieu de prédilection with its abundance of idyllic scenery. With one of the era’s favourite medium: watercolour, this quick and portable kit for traveling men gives many of their paintings a certain simplicity retracing their penchant for a sense of the picturesque reminiscent of Constable and Turner. It is through these works that Bishop Mountain and William Dawson expressed their ever growing love for their terre d’accueil.

Progress that transcends time

By trying (or not) to read between these well-conserved sepia-toned cursive lines, you realize that Bishop Mountain and Dr. Dawson were simply men of their times. The former, whose solemn profile does not do justice to his bright youthful locks, and the latter who goes from a young Dorian Gray to an old Walt Whitman in his lifetime. A true testimony to the hard work they put in their careers with a care for education and somewhat liberalism which was deemed majorly progressive for the era.

McGill University Archives, MG 1022, c.21, “Illustrations de Biography”, Unknown artist (left and center), M. Brooks (right), pp.101, 105, 107.

Nevertheless, amongst the decades-old and quite fairly eerie stacks, these deeply personal possessions filled with artistry and sentimentality make our archives standout––hautes en couleurs––inside McLennan’s concrete walls. It even makes us ponder: who would have thought a bishop and a scientist could be so romantic?

Sources

To discover more…

https://www.mcgill.ca/library/branches/mua

https://archivalcollections.library.mcgill.ca/index.php/mountain-family-fonds

https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/sir-john-william-dawson/

https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/george-mercer-dawson/

http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/mountain_george_jehoshaphat_9E.html

https://www.mcgill.ca/principal/about/past

Frost, Stanley Brice. McGill University : For the Advancement of Learning, 1801-1895. Volume I. Montreal : McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1980

Moodie, Susanna. “A VISIT TO GROSSE ISLE.” Roughing It in the Bush or Life in Canada, edited by Carl Ballstadt, McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1995, pp. 12–25. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt80k32.10.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.