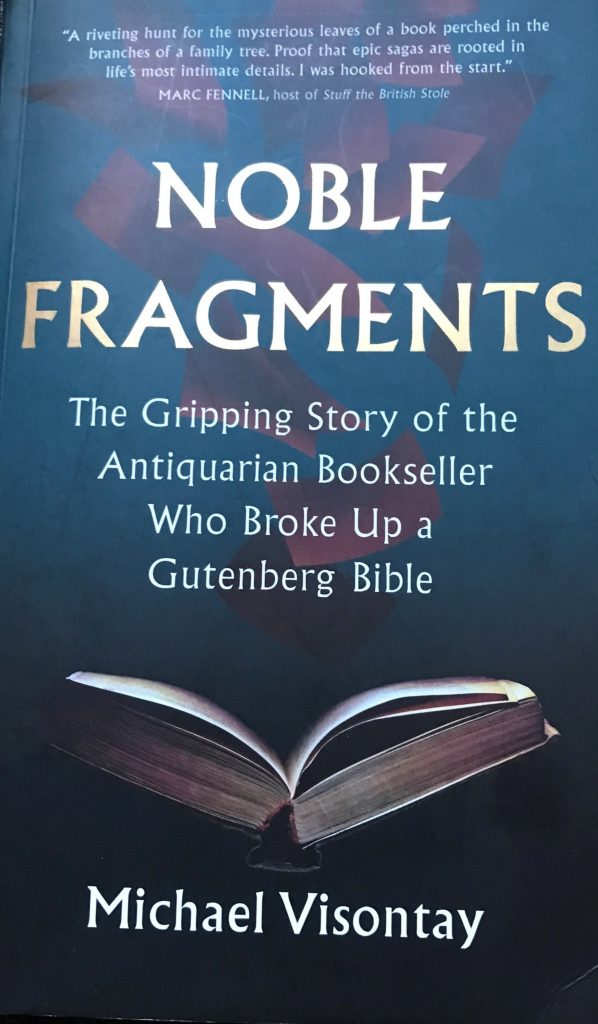

We had the great pleasure of chatting over a video conference call with author and journalist Michael Visontay, residing in Sydney, Australia, following the release of his most recent book Noble Fragments. It recounts the riveting story of Gabriel Wells, a key figure of the antiquarian book trade, who dared to break up a Gutenberg Bible for commercial profit.

The reader is taken back to a moment in time, at the turn of the 20th century, when Gutenberg bibles were highly sought after as a great prize for discerning collectors. This brilliantly written book depicts a kind of class warfare, where old money meets new world ambitions; and where the fortunes and reputations of the antiquarian dealers were made or broken as high-risk ventures were carried out on an extremely competitive book market.

The Gutenberg Bible, named after its printer Johann Gutenberg (d. 1468), is the first substantial book printed in Europe produced by means of a wooden screw hand-press and moveable metal type. As a direct result, multiple copies and fixity of text were made possible, thus laying the foundation for the tremendous rise in European culture and literacy. This is not the first book printed with moveable type (China); nor the first book printed with moveable metal type (Korea); nor the first trial printing by Johann Gutenberg. However, symbolically-speaking, it is the largest printing enterprise that highly influenced a technological revolution.

The Bible was prepared and printed in two volumes between 1450 -1455. The total print run is estimated by scholars to be about 180 copies. Extant copies of bound volumes stand at 48-49 copies in the world, now held entirely in institutions.

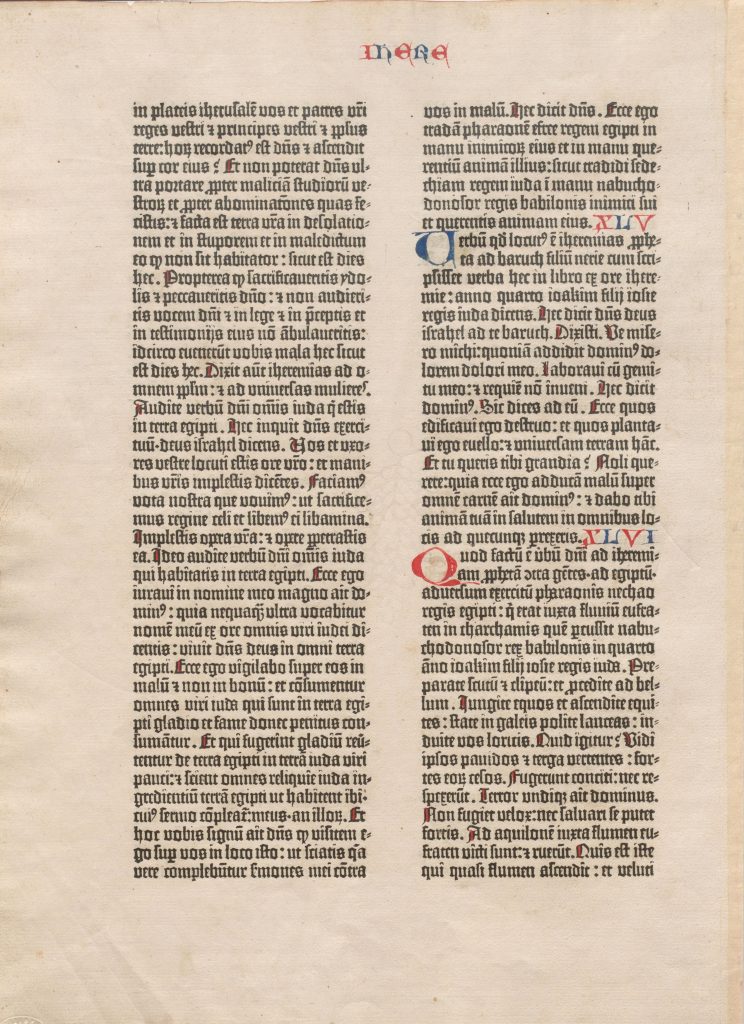

Several features of the Gutenberg Bible set it apart as an exquisite exemplar of print culture. The type is a bold and stately Gothic letter modeled on the “Textura” hand script. The ink is thick and deeply black, which makes the characters stand out on the high-quality white paper imported from Italy. The page layout is in double columns, perfectly justified to an even margin, with 42-lines of type to the page.It contains portions of the text of Jeremiah, based on the Latin Vulgate version of the Old Testament.

Each copy is unique due to hand-embellishments executed subsequent to the printing. Gutenberg expected that his Bible would eventually be ornamented with large and small initials, elaborately decorated and possibly illuminated in gold. To this end, he ensured that the margins were generous to accommodate hand-finishing. The total page design was meant to imitate late medieval liturgical manuscripts.

Our conversation with Visontay helped to pinpoint the finer details of the acquisition of McGill’s copy. About one hundred years ago, a two–volume set of an imperfect Gutenberg Bible (having parts mutilated or damaged and missing 53 leaves) was broken up by a noteworthy New York antiquarian bookseller named Gabriel Wells in 1921 and sold either as single leaves, or small sections representing key moments in the Bible.

Provenance: How did Wells obtain this copy? It was at the sale at Sotheby’s in London on the 9th of November 1920 when a bound Gutenberg Bible was sold by the British descendants of the aristocrat Robert Curzon to Joseph Sabin. The latter then quickly resold it to Wells, who finally decided to dismantle the Bible which was missing too many pages to resell as an intact copy so he produced a leaf book.

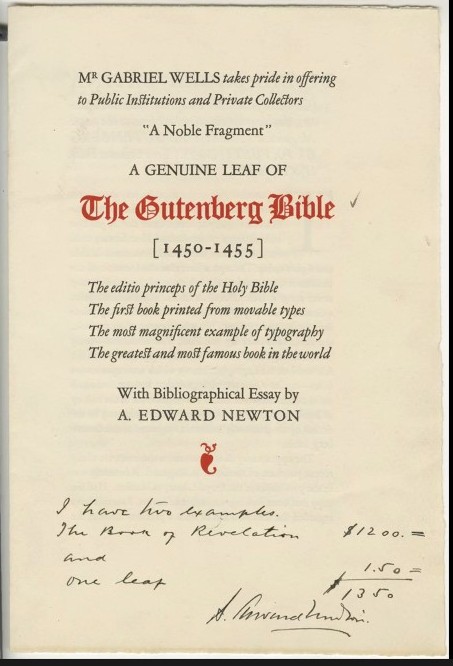

A leaf book celebrates a famous text and includes one or more pages (or leaves) laid inside a bound volume, introduced by a published essay. Specimens of leaves from noteworthy books, manuscripts included, circulated as leaf books as early as the mid 19thcentury.The first commercial enterprise involved the Gutenberg Bible, “the most famous and probably the most influential leaf book of them all”[i].

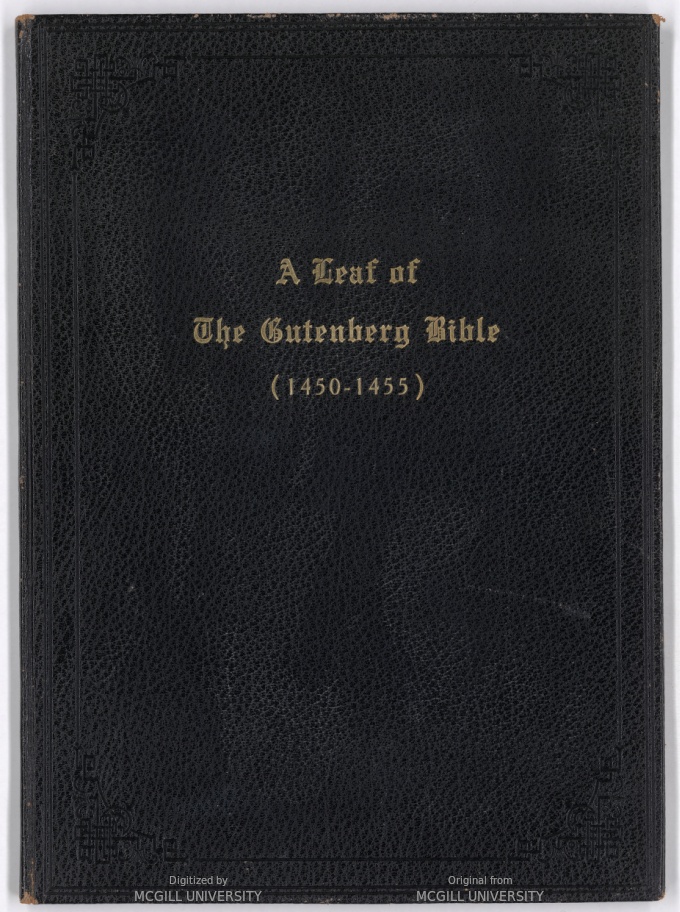

Appealing to the bibliophile, the inserts were distributed with a scholarly essay by Edward Newton, designed by the highly-regarded American typographer Bruce Rogers, and printed at the shop of William Edwin Rudge, New York in 1921. The original leaf or leaves came packaged in a special binding signed by “Stikeman & Co. NY”, with gilt lettering on the front cover, using a clever Gothic font.

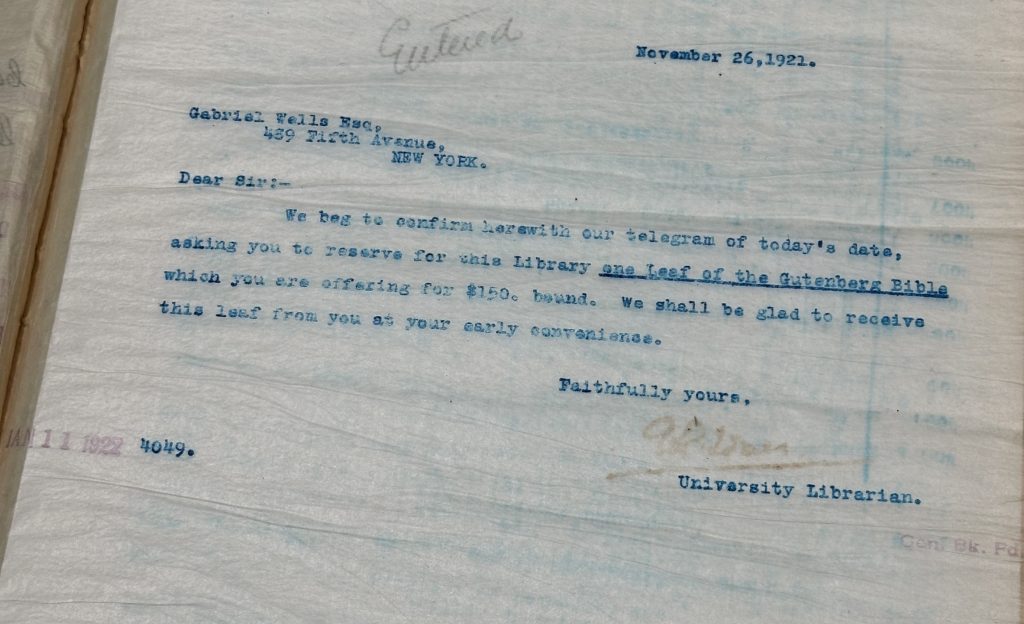

McGill’s Noble Fragment was ordered by telegram on November 26th, 1921 by the University Librarian Dr. Gerhard Lomer – possibly from a prospectus printed up by Gabriel Wells. Our copy was accessioned by the Libraries on January 11th 1922.

Early in Visontay’s book[ii], McGill University is cited as one of the first institutions to reserve a copy at the very moment of its issue, in the good company of: MIT; the Smithsonian Institute; the University of Pennsylvania; Vassar College, and the Boston Public Library.

Gabriel Wells priced a single leaf without flaw at $150.USD. A single leaf of the Gutenberg Bible today is valued at about $100,000.CDN. Because our copy never went through further wear and tear, it remains a very good representative of the leaf book in its original form.

Visontay points out how quickly the news spread, and adds: “The readiness to buy the leaf testifies to the significance of the opportunity of owning a part of this landmark printing”. Indeed, at the time Lomer was eagerly collecting extraordinary specimens of book history for a long-term display at “The Museum” of the old Redpath Library.

The moral question of breaking up significant books in order to market and disseminate individual leaves was controversial. An entire Gutenberg Bible was worth much less than the sum of its parts. But to break up “a monument as supreme as Gutenberg”[iii], celebrated as the first of all printed books, was indeed audacious on many levels, not the least of which was the disruption of the integrity of the physical artifact. On the other hand, these dispersed leaves allowed defective bound copies to become complete. More importantly, they provided an opportunity for wider audiences to possess a piece of the most famous book in the Western World. As a result, hundreds of rare book repositories make use of these fragments for teaching purposes and public exhibits. To his credit, Gabriel Wells dispersed several bundles at low rates and donated three leaves to the New York Public Library to help complete their incomplete copy, the first GB on American soil.

Bible’s impact on Visontay’s family

Another positive outcome was “Gutenberg’s invisible imprint on the author’s life.” The narrative in the book is entwined with a poignant family epic that touches upon the human tragedy of Hungarian Holocaust survivors, family members of the author, who fortunately benefited from the profits years later. Upon his death in 1946, Wells gave his inheritance to six beneficiaries, one of whom was his niece Olga, the second wife of the author’s grandfather. For this family in dire straits, the inheritance was used to rebuild a life in Sydney Australia, to open a family business-then a delicatessen, and now a shop they still own today.

Noble Fragment leaf book- surviving copies:

Visontay contributes significant information on their whereabouts. Wells had nearly 600 leaves at his disposal. From these, it is estimated that of 400 leaf books produced, about 120 copies have been traced. In Australia and New Zealand, Visontay identified 10 or 11 Noble Fragment leaf books with the caveat “subject to subsequent sales”, as some are still in private hands. A preliminary glance at recorded holdings reveals the existence of over 81 such leaf books in the USA.

A Census of copies held in Canada is underway.

Apart from McGill’s copy, current research uncovers a Noble Fragment leaf book in Ottawa (Library and Archives Canada); and in Vancouver (Vancouver Public Library)- the latter copy was seen by Visontay on his many travels and public speaking tours about the book. We hope to have a turn at a live presentation in Rare Books and Special Collections in the company of this generous author, still on the hunt.

For any information on locations in Canada, please contact the Curator, Ann Marie Holland, McGill University Library, Rare Books and Special Collections, ann.maire.holland@mcgill.ca.

[i] Christopher De Hamel, Joel Silver et al., Disbound and Dispersed: The Leaf Book Considered. Chicago: Caxton Club, 2005, p.14.

[ii] Michael Visontay, Noble Fragments The Gripping Story of the Antiquarian Bookseller Who Broke Up a Gutenberg Bible. Melbourne: Scribe Publications, 2025, p.27.

[iii] De Hamel, Disbound and Dispersed, 2005, p.14.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.