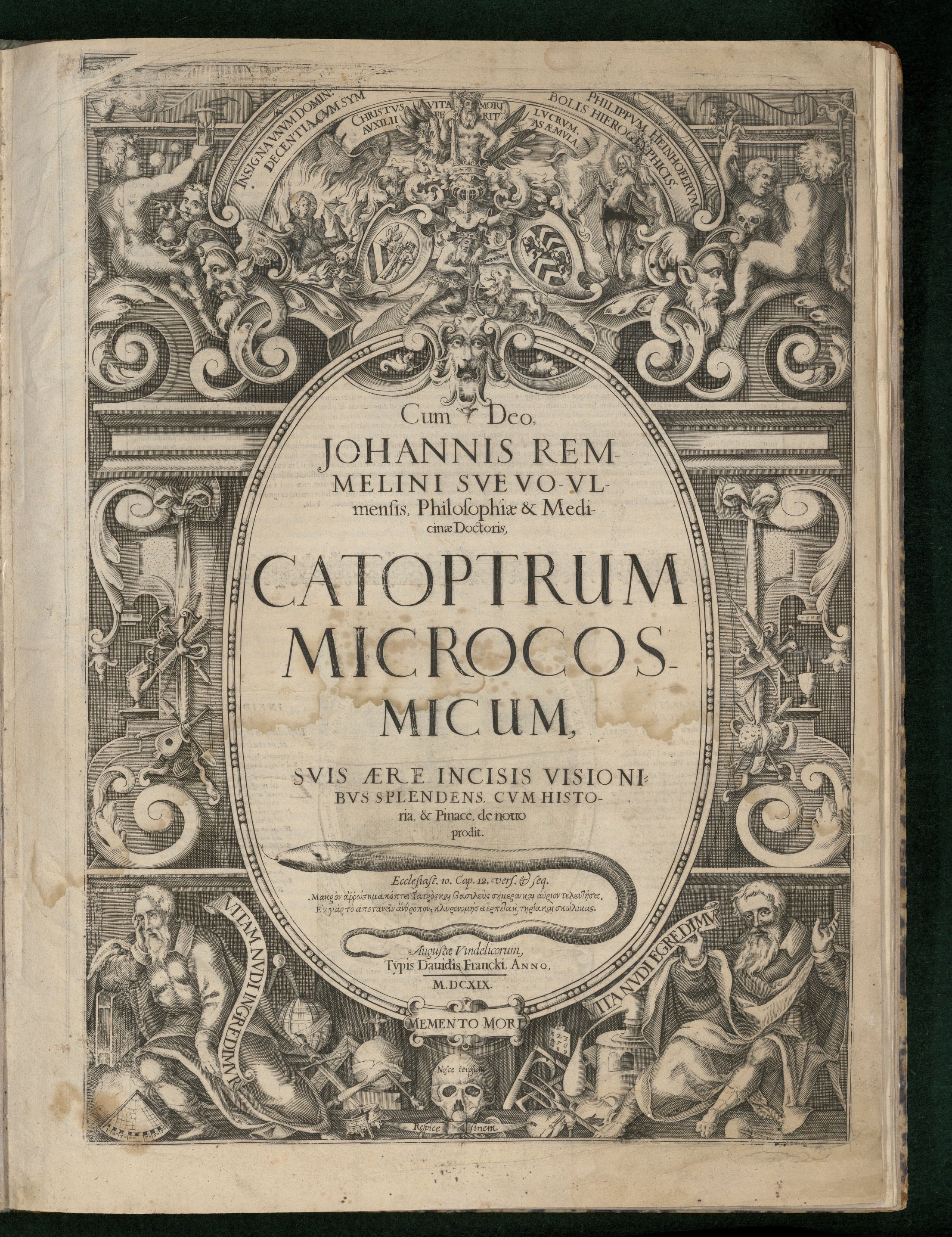

Title page of Johann Remmelin’s 1619 Catoptrum microcosmimum, showing the tools of medical and scientific inquiry.

By Ruoshan Gu and Mary Hague-Yearl

The staff at the Osler Library are always on the lookout for new ways to challenge our colleagues in Digital Initiatives. The team in the digitization lab seem to be able to do anything, so we wondered how they would handle a personal favourite at the Osler Library: Johann Remmelin’s Catoptrum Microcosmicum ([Augsburg], 1619). It goes without saying that we were impressed with the results of the work carried out by Rozerin Akkus, Ruoshan Gu, Manyang Lual Jok, Qi Qi, and Yanliu Yao, under the careful guidance of Digitization Administrator Greg Houston.

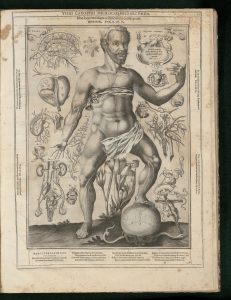

The library owns three volumes by German physician Johann Remmelin (1583-1628), two of which are elephant folio-sized works that follow the tradition of anatomical fugitive sheets (see Carlino, “Knowe Thyself”). What is particularly interesting about the 1619 printing is not only the extensiveness of the anatomical flaps, but also the inclusion of the devil covering the female genitalia (see Eggert, 177-180). The visually striking nature of this work, and that it is the first authorized printing of Catoptrum microcosmicum, were deciding factors in selecting this volume to test digitization approaches.

The second Remmelin elephant folio edition held by the Osler Library is from about eighty years later and was printed in London (1702), in English: A Survey of the Microcosme, or, the Anatomy of the Bodies of Man and Woman … As That All the Parts of the Said Bodies, Both Internal and External Are Exactly Represented in Their Proper Site Useful for All Physicians, Chyrurgeons, Statuaries, Painters, &c. This one lacks the defining feature of the 1619 German printing: namely, the association of the devil with the female figure. Though this copy from the Osler’s collections has not yet been digitized, it is one to look out for in the future.

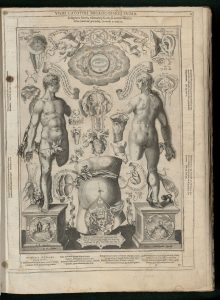

Flap anatomy books in general are fascinating for the layers of detail they provide: they are essentially a paper dissection or a “corporal dismembering” (La Marchand, 28). They provide extensive information about anatomy in a way that appealed to educated laymen who may nonetheless have learned more effectively through image than through text (Carlino, 68). The works were clearly popular; Remmelin’s work was translated from Latin into German, Dutch, English, and French. Flap anatomies such as Remmelin’s provided a startling image of the body, traveling first through the superficial layers, then through blood vessels, muscles, nerves, and finally to the body’s core as represented by the spine. The ears, the eyes, the torso with its organs, were dealt with in separate figures. Though many digitized works show only the top level of these works, McGill’s Digital Initiatives team took on the challenge of representing the many layers of the body as microcosm.

The process of engaging with this work as part of the digitization process is described here by McGill MISt (Master of Information Studies) student Ruoshan Gu:

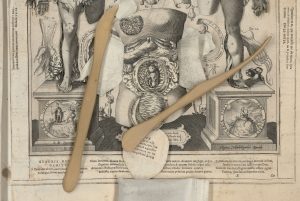

As part of our class project, we participated in the digitization process of this incredible 17th-century anatomical flap book. It illustrates successive layers of human anatomy with flaps and moveable parts. Even though Remmelin was not the pioneer in producing this type of paper materiality, we were nevertheless very impressed with how instructional and detailed these flaps are. The first challenge came to our mind was that digitizing these flaps piece by piece requires strenuous work and attentiveness. The book bears hundreds of years of history and some of its paper is brittle, which means we must be very careful turning all the pages, especially those delicate anatomical sheets with moveable parts.

The entire experience was fascinating. We gently opened the first layer of the abdomen on a nude female torso on Visio Prima (p.9) by hand. After scanning the first image, we continuously lifted each layer to see and scan the next internal organ as it would appear in autopsy until we reached the last layer, where a baby developing in the uterus appeared. During the process, in order to keep the layers flat and open for scanning, we put a small wooden spatula on the edge of the opening side of the flap. In cases where all flaps were opened, we put weight bags on them to keep them from closing.

Another observation we had when we scanned a nude male body on Visio Secvnda (p.15) was worth mentioning as well. The chest area of the male body contained many layers and most of them were moveable parts such as the stomach and the respiratory system. We were amazed that these nicely designed and crafted illustrations were intact. Although few parts were glued together unintentionally, we were able to scan most of the moveable pieces in order.

The book is a remarkable masterpiece by Remmelin in our opinion. Despite the time-consuming effort and patience during the digitization process, there is a great value to digitizing such works to make these paper dissections more accessible to everyone.

* * *

Thanks to a well-orchestrated team effort, Johann Remmelin’s intriguing and popular mirror into the microcosm, Catoptrum microcosmicum, is now available in the Osler Library’s Archive.org collection to scholars and others interested in comparing the Osler Library’s digital edition of Catoptrum microcosmicum to other copies of Remmelin flap anatomies that have been digitized at peer institutions. Notably, the Augustus C. Long Health Sciences Library documented their own journey to digitize a later German edition of Remmelin’s work.

Page 9 of Catoptrum microcosmicum, showing several figures with flap detail: male and female bodies, the eye, the ear, the heavens at the top and the female torso at the bottom.

Additional notes:

- In addition to the digital book that is described here, there is also a video of the book being opened, filmed by 2018 Larose-Osler Artist-in-Residence Caroline Boileau: https://www.carolineboileau.com/pages/corps-qui-hantent-dautres-corps-1

- The third Remmelin work at the Osler Library is actually two works bound together. Representing numbers 3790 and 3791 in the Bibliotheca Osleriana (the original catalogue of the library Sir William Osler donated to McGill), they are: Pinax Microcosmographicus, published in Latin in 1615 (place not identified), followed by Elucidarius, Tabulis synopticis, Microcosmici laminis incisi aeneis… (n.p., 1614). These works are a small quarto size and have no illustrations other than on the title page of Pinax Microcosmographicus.

Sources cited:

Carlino, Andrea. “Knowe Thyself: Anatomical Figures in Early Modern Europe.” RES: Anthropology and Aesthetics 27 (Spring 1995): 52-69. https://www.jstor.org/stable/20166917

Eggert, Katherine. Disknowledge: Literature, Alchemy, and the End of Humanism in Renaissance England (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2015). https://muse.jhu.edu/book/41855

Le Marchand, Bérénice. “Specular Dissection in French Renaissance Literary Blasons.” Dalhousie French Studies 92 (Fall 2010): 21-31. https://www.jstor.org/stable/41705532

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.