‘… [A]fter learning a little Botany it seems almost impossible to stop.’ (Elizabeth Gwillim, 1805)

The Gwillim Project, funded through a grant from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council, began in May 2019. It focuses on the unique paintings and letters of two English sisters, Elizabeth Gwillim (1763-1807) and Mary Symonds (b. 1772), who lived in Madras (now Chennai), India, at the beginning of the nineteenth century. Members of the Gwillim Project have already been making exciting new discoveries in the archives, and several relate to Elizabeth’s involvement in botany. While most of her paintings in the Blacker Wood collection are zoological, some are also of plants. Elizabeth maintained botanical networks in both England and India, sending plants to friends and family, collectors, and commercial nurseries.

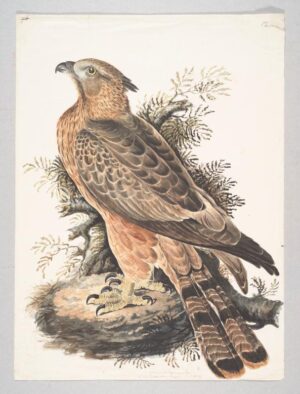

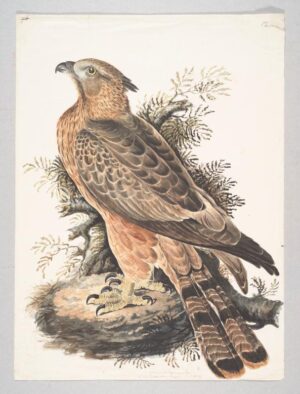

Elizabeth Gwillim. Honey Buzzard with Mimosa Written on back of painting: “’No. 152. Falco’; with a slight sketch of a species of Mimosa with yellow blooms sweet but faetid wood.” Blacker-Wood Collection, Rare Books and Special Collections.

In England, the Gwillim family had close social relations with the Thoburn family. Frank Thoburn (d. 1790) founded a nursery at Brompton, Kensington in 1784, which was known for introducing exotic plants. His daughters Elizabeth (or Lizzie) (1783-1855) and Mary Thoburn were contemporaries and friends of the Gwillim/ Symonds sisters and are mentioned frequently in the correspondence. Botanical relationships overlapped with personal ones, Elizabeth Gwillim refers to sending seeds to Lizzie Thoburn as well as Indian fabric to make gowns for her and her sister. The sisters were also close to Reginald Whitley (1754-1835), Frank Thoburn’s business partner who continued the nursery after Thoburn’s death and married his widow. Elizabeth collected seriously for Whitley, on occasion sending him living trees and seeds and she also relayed to him collections made by other botanists. Her contributions were also cited in the celebrated botanical journal of the period – Curtis’s Botanical Magazine. The editor, Dr John Sims (1749-1831), praised both Elizabeth’s accurate and graceful drawings as well as her role as ‘the patroness of science in that Presidency.’

In Madras, Elizabeth Gwillim established important botanical connections, with both Indian and European contemporaries. In her letter of 1805 in which she discusses studying botany, she remarks that:

The truth is I should not have put myself upon so new & difficult a study, but that without some little knowledge of Botany it is impossible to read the Hindoo language: their allusions to particular plants which are essential to their different ceremonies, are so pointed that unless you know the plants, which Botany alone can teach you, the merit of the whole passage is lost.

Elizabeth’s reference to the ‘Hindoo language’ here refers to Telugu, which she had begun learning soon after her arrival and by 1803 claimed that she could write a letter. Elizabeth used her language skills to communicate with her servants, who also served as botanical informants. As she wrote in 1802, they were ‘constantly bringing me flowers & insects & pointing out things to me as we go along’.

European plant enthusiasts with whom Elizabeth Gwillim established contacts in Madras included the Governor, Lord Edward Clive and his wife. Although they did not meet, Elizabeth knew that Lady Clive, delighted [in] this country and made large collections of curiosities.’ Mary also wrote about Lord Clive’s love of gardening, for which he was apparently teased in the settlement. She added ‘but in the affairs of the Government he is a mere child & knows no more what is doing than I do’.

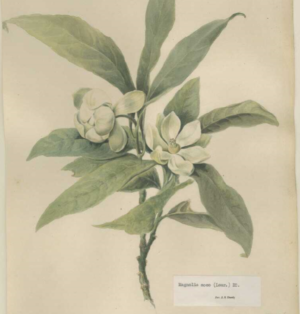

The sisters found more serious botanical contacts among the East India Company’s surgeons, who were often trained in botany, including Dr James Anderson, with whom Elizabeth exchanged seeds. Elizabeth also worked with Dr J. P. Rottler (1749-1836), originally a missionary at the Tranquebar and later at the Vepery missions near Madras. While working in the Linnaean Society in London, Dr Henry Noltie, an expert in the history of botany in India and one of the Gwillim project participants found a previously unknown watercolour painting by Elizabeth Gwillim among the papers of Society’s founder J.E. Smith (1759-1828). The painting shows the species of magnolia that was named Gwillimia indica by the botanist J.P. Rottler. Rottler’s letter to Smith praises Elizabeth’s ‘love and application to botany’ and notes that she had also sent a specimen of the plant to England.

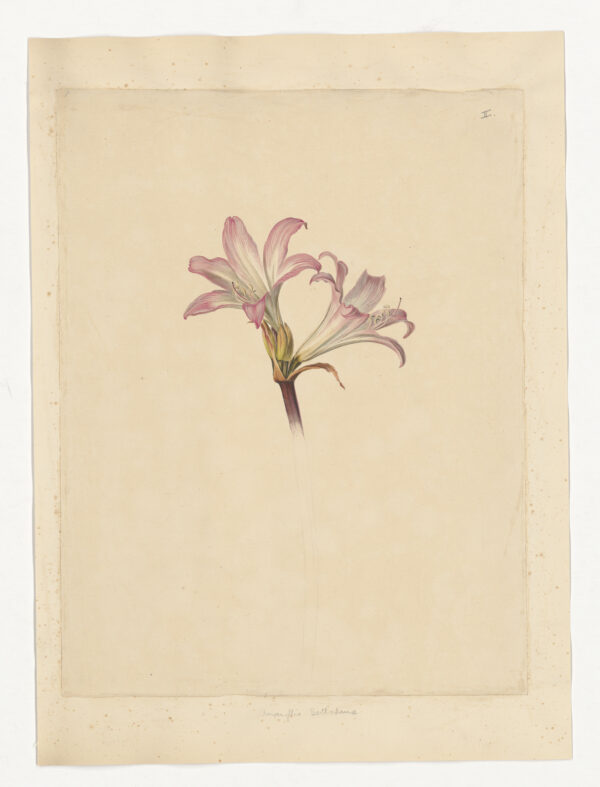

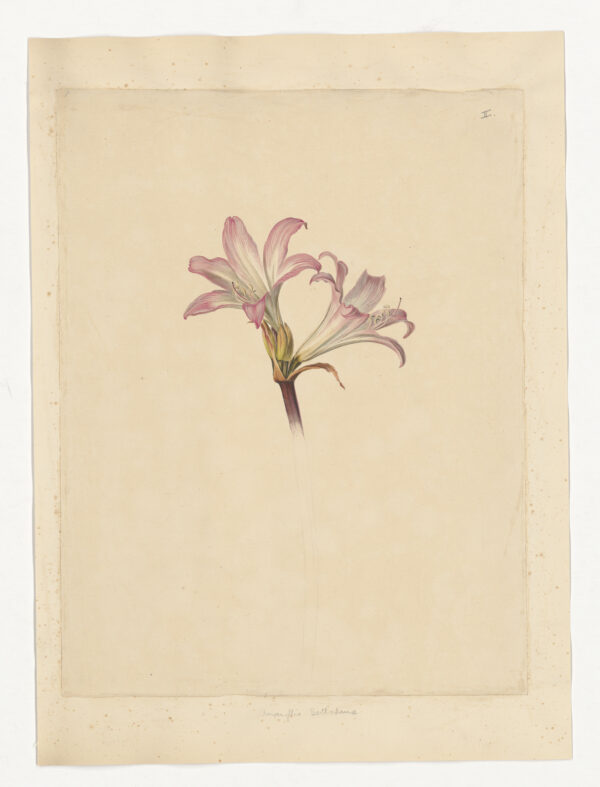

In her own description of the magnolia written in 1805, Elizabeth noted that it was not in fact a local plant, but that ‘it came from Batavia (modern Jakarta) & is there called Sampa Ialaca – which means milk flower’. In fact, several of the other paintings in the Blacker Wood collection are also not of Indian plants. These include the ‘China astor’ and the ‘Amaryllis belladonna’, native to China and South Africa respectively. Elizabeth refers to raising seeds from the Cape of Good Hope in a letter of 1801, so perhaps the Amaryllis was one of the exotic flowers she cultivated in Madras. We hope to solve these puzzles and find more of Elizabeth Gwillim’s botanical work as the project goes forward!

Elizabeth Gwillim. Amaryllis belladonna. Watercolour painting. Blacker-Wood Collection, Rare Books and Special Collections.

By: Anna Winterbottom

Les réseaux de botanique d’Elizabeth Gwillim

« … sitôt que j’eus appris un peu en botanique, ma passion s’est enflammée. » (traduction libre) (Elizabeth Gwillim, 1805)

Le projet Gwillim, mis sur pied grâce à une subvention du Conseil de recherches en sciences humaines, s’est amorcé en mai 2019. Il porte sur les peintures et les lettres uniques de deux sœurs anglaises, Elizabeth Gwillim (1763-1807) et Mary Symonds (née en 1772), qui vivaient à Madras (aujourd’hui Chennai), en Inde, au début du XIXe siècle. Les membres du projet Gwillim font déjà fait des découvertes passionnantes dans les archives, plusieurs sur le travail d’Elizabeth en botanique. Si la plupart de ses tableaux dans la collection Blacker Wood dépeignent des animaux, certaines représentent aussi des plantes. Elizabeth entretenait des réseaux de botanique en Angleterre et en Inde, par l’envoi de plantes à ses amis et membres de sa famille, à des collectionneurs, ainsi qu’à des pépinières commerciales.

Elizabeth Gwillim. Honey Buzzard with Mimosa Written on Back of Painting: “’No. 152. Falco’; with a slight sketch of a species of Mimosa with yellow blooms sweet but faetid wood.” Peinture aquarelle. Collection Blacker-Wood, Livres rares et des collections spécialisées.

En Angleterre, la famille Gwillim était très proche de la famille Thoburn. Frank Thoburn (mort en 1790) a fondé en 1784 une pépinière à Brompton, dans le borough de Kensington, connue pour l’introduction de plantes exotiques. Les noms de ses filles Elizabeth – ou Lizzie – (1783-1855) et Mary Thoburn, contemporaines et amies des sœurs Gwillim/Symonds, reviennent souvent dans la correspondance. Et on y observe que botanique et amitié ne font qu’un, alors qu’Elizabeth Gwillim traite de l’envoi de semences à Lizzie Thoburn, mais aussi de tissu indien avec lequel elle et sa sœur pourraient se confectionner des robes. Les sœurs sont également proches de Reginald Whitley (1754-1835), l’associé de Frank Thoburn, qui, après la mort de ce dernier, poursuit l’exploitation de la pépinière et épouse sa veuve. Elizabeth travaille sérieusement pour Whitley, lui expédiant à l’occasion des arbres en vie et des semences, en plus de lui relayer le fruit de la cueillette d’autres botanistes. Il est aussi question de ses contributions dans la célèbre revue de botanique de l’époque, Curtis’s Botanical Magazine. Le rédacteur en chef, le Dr John Sims (1749-1831), y fait l’éloge de la précision et la grâce des illustrations d’Elizabeth, ainsi que de son rôle de « patronne de la science en cette présidence ».

À Madras, Elizabeth Gwillim noue d’importantes relations en botanique, autant avec ses contemporains indiens qu’européens. Dans une lettre qu’elle écrit en 1805 sur l’étude de la botanique, elle formule l’observation suivante :

À vrai dire, je ne me serais pas lancée dans une étude aussi nouvelle et poussée, car, sans quelque connaissance en botanique, il est impossible d’interpréter le sens de certains passages en langue hindoue : ses allusions à des plantes particulières, essentielles à différentes cérémonies, sont si pointues, que rien d’autre qu’une connaissance des plantes tirée de la botanique ne peut le permettre. (traduction libre)

En fait, Elizabeth fait ici référence au télougou, langue qu’elle a commencé à apprendre peu après son arrivée. En 1803, elle affirme la maîtriser suffisamment pour écrire une lettre. Cette compétence linguistique lui sert à communiquer avec ses domestiques, qui sont également pour elle des informateurs en botanique. « Constamment, ils m’apportaient fleurs et insectes en me pointant du doigt différentes choses », écrit-elle en 1802.

Parmi les passionnés européens de botanique avec lesquels Elizabeth Gwillim a fait contact à Madras, il y a le gouverneur Lord Edward Clive et son épouse. Sans l’avoir rencontrée en personne, Elizabeth sait Lady Clive « émerveillée par ce pays et détentrice d’importantes collections de curiosités. » Mary Symonds écrit aussi sur l’amour que voue Lord Clive au jardinage, qui, apparemment, lui vaut des taquineries au sein de la colonie. Mais, « pris dans les affaires du gouvernement, il en est qu’à l’enfance du savoir, tout comme moi », ajoute-t-elle.

Les sœurs se font des contacts plus sérieux chez les chirurgiens de la Compagnie britannique des Indes orientales, souvent formés en botanique, notamment le Dr James Anderson, avec qui Elizabeth échange des semences. Cette dernière collabore également avec J. P. Rottler (1749‑1836), d’abord missionnaire à Tranquebar et plus tard à Vepery, près de Madras. Au cours de ses travaux à la Linnaean Society de Londres, le professeur Henry Noltie, expert en histoire de la botanique en Inde et participant au projet Gwillim, découvre une aquarelle d’Elizabeth Gwillim, jusqu’alors inconnue, dans les papiers du fondateur de la société, J.E. Smith (1759-1828). Le tableau représente l’espèce de magnolia nommée Gwillimia indica par le botaniste J.P. Rottler. La lettre adressée de Rottler à Smith louange « l’amour et l’application d’Elizabeth pour la botanique », et raconte qu’elle avait également envoyé un spécimen de la plante en Angleterre.

Dans sa propre description du magnolia, en 1805, Elizabeth explique qu’il ne s’agit pas d’une plante locale, mais plutôt « de Batavia » (aujourd’hui Jakarta), et qu’elle s’y nomme Sampa Ialaca, ce qui signifie fleur de lait ». En fait, plusieurs des autres peintures de la collection Blacker Wood représentent aussi des plantes non indiennes, par exemple la « reine‑marguerite » et l’« amaryllide belladone », des espèces chinoise et sud-africaine, respectivement. Dans une lettre de 1801, Elizabeth parle de culture de semences du Cap de Bonne Espérance. On peut donc penser que l’amaryllide est l’une des fleurs exotiques qu’elle cultive à Madras. Nous espérons résoudre ces énigmes et découvrir d’autres travaux de botanique d’Elizabeth Gwillim au fil du projet!

Elizabeth Gwillim. Amaryllis belladonna. Peinture aquarelle. Collection Blacker-Wood, Livres rares et des collections spécialisées.

Par: Anna Winterbottom

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.