From collecting specimens and serving as scientific illustrators to conducting and publishing research, authoring natural history books, and more, women have overcome many social and cultural obstacles and gender barriers to help further our understanding of the natural world. Biodiversity Heritage Library, #HerNaturalHistory Campaign Report, 2019

Last spring, Rare Books and Special Collections took part in Her Natural History, an international campaign led by the Biodiversity Heritage Library, aimed at highlighting the role of women in natural history. We invite you to explore the following articles, each shedding light on powerful and persistent women who achieved greatness in the sciences. We hope they inspire you.

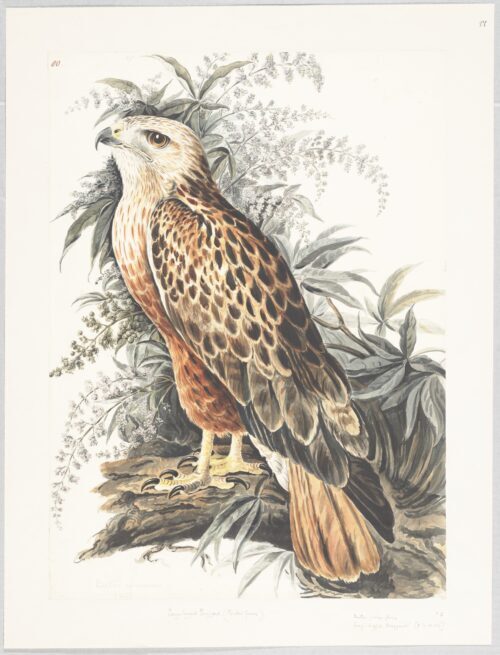

1. 121 paintings of Indian birds by Elizabeth Gwillim, 1801-1807.

Elizabeth Gwillim’s husband was a judge in their native Britain, but during the period of Britain’s colonial rule over India, Sir Henry was sent to Madras (now Chennai) to serve there on the supreme court. Lady Gwillim was eager to explore her new surroundings – to learn about the Indian people and their customs, and about the unfamiliar landscape and animals that she could see just outside her door. As with most upper class women of that period, she had taken painting lessons throughout her youth; so she put her artistic skills to work, and set out into the jungle to paint as many birds as she could find. Praised by modern ornithologists for their scientific accuracy, these paintings have recently become the subject of a number of exciting research projects. And while Audubon is often credited with being the first artist to paint life-sized bird portraits, Gwillim was doing this nearly 30 years earlier.

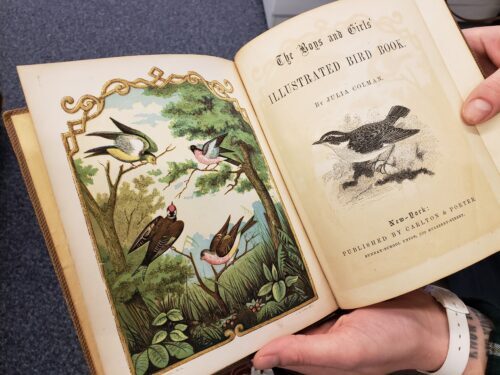

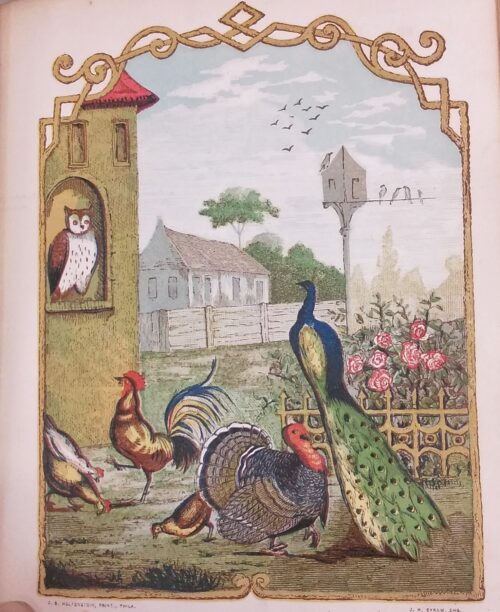

2. The Boys and Girls’ Illustrated Bird Book by Julia Colman, 1857.

Julia Colman (1828 – 1909) was superintendent of the Women’s Christian Temperance Union’s literature department as well as an immensely capable scientific mind. Before formally studying science and foreign languages at university, she taught herself botany; independently classifying hundreds of specimens. The Boys and Girls’ Illustrated Bird Book was her first book. She went on to write others, as well as many articles and pamphlets, most of which had a scientific aspect to them.

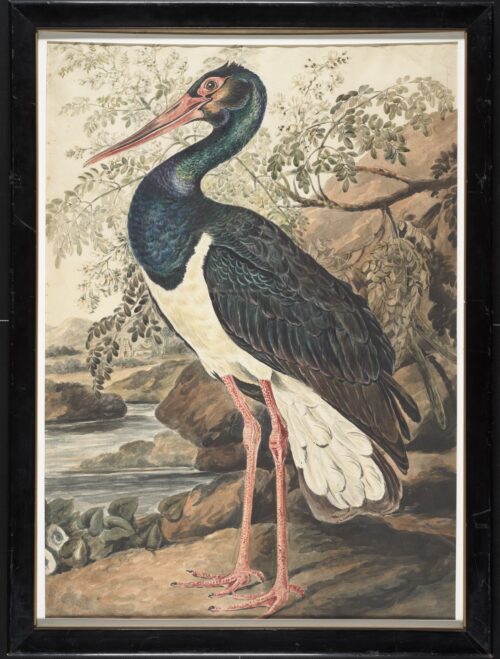

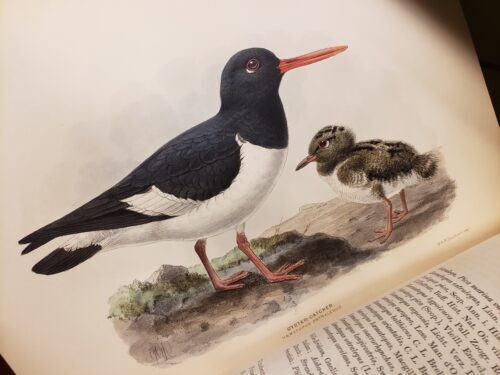

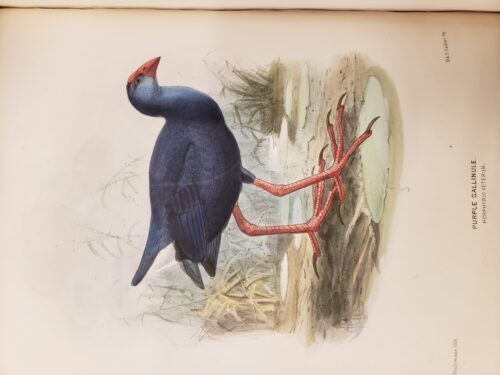

3. A history of the birds of Europe : including all the species inhabiting the Western Palaearctic Region by Henry Dresser, 1871-1872.

Henry Dresser’s Birds of Europe was published in 84 parts between 1871-1872. The remarkable illustrations, done mainly by renowned naturalist-artist J.G. Kuelmans, depict the 634 species of birds described by Dresser. Using the lithographic process, Kuelmans created the black outline of his illustrations, and then finished them with watercolour paint. However, he only completed one ‘master copy’ in this fashion; the quarter of a million additional illustrations that would wind up as plates in the published book were painted in watercolours by women at colourist workshops. Using Kuelmans’ master copy as a guide, the women worked in assembly-line style, each of them adding one colour to the plates before passing them along to the next person. Dresser credits Kuelmans on the title page of this monumental work, but the names of these women artists are lost to history.

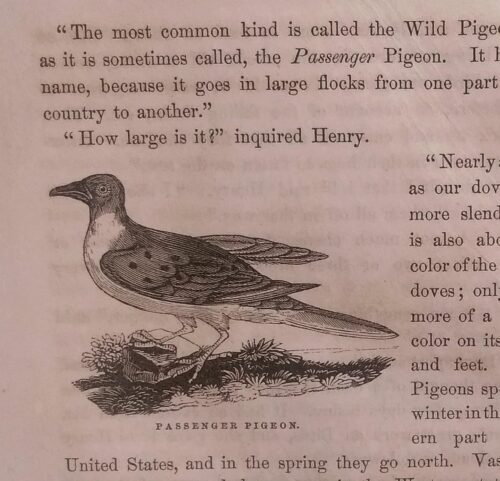

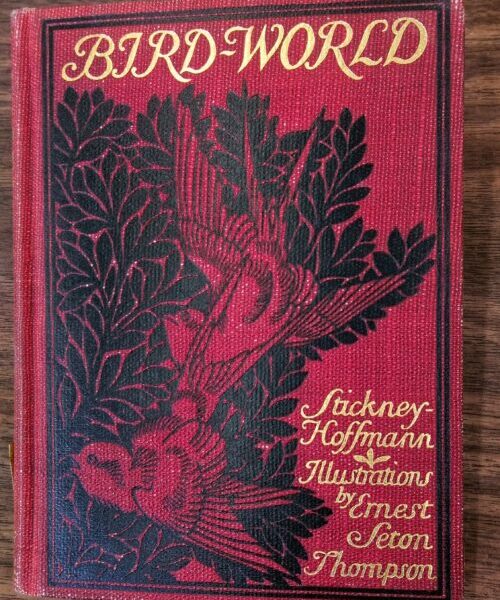

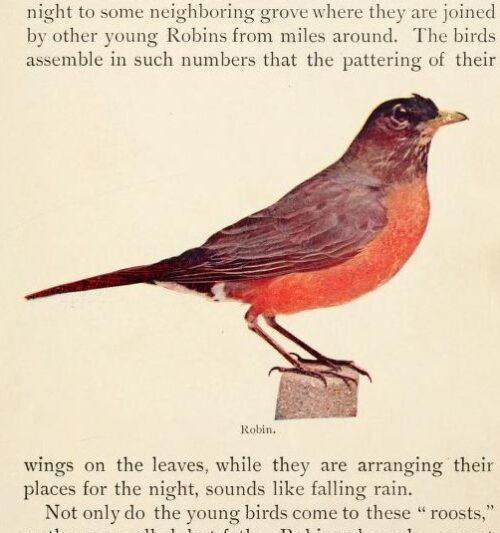

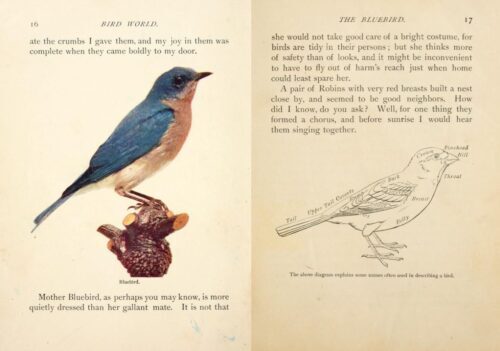

4. Bird World : A Bird Book for Children by J.H. Stickney, 1898.

Jenny H. Stickney (1840 – unknown) was principal of the Boston Training School for Teachers as well as a successful editor and author; one of the first female educators to gain prominence in the publishing world at a time when female teachers were becoming increasingly numerous in the public school system. Bird World, like Colman’s Bird Book, takes on a conversational tone that combines poetry and anecdotes with factual information, reflecting an understanding of children’s minds and interests.

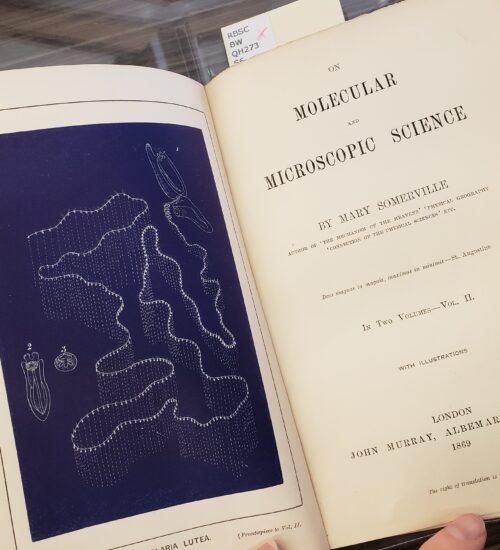

5. On molecular and microscopic science by Mary Somerville, 1869.

Mary Somerville (1780 – 1872) was a Scottish polymath whose earlier treatise On the Connexion of the Physical Sciences brought together the worlds of mathematics, astronomy, geology, chemistry, and physics so clearly, that her work became the textbook for Cambridge University’s first science curriculum. Prior to this publication, the term ‘man of science’ had been used to describe anyone whose research belonged to one of these scientific disciplines. But upon reading Somerville’s treatise, Cambridge don William Whewell coined the term ‘scientist’ to describe Somerville, as ‘man of science’ seemed inappropriate. He explained that ‘scientist’ was a more accurate description of her work not only because of her gender, but because of the interdisciplinary nature of her research.

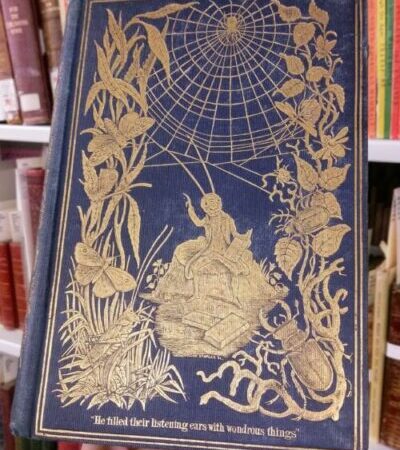

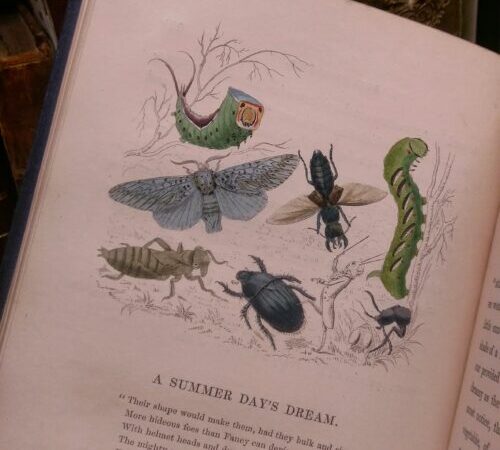

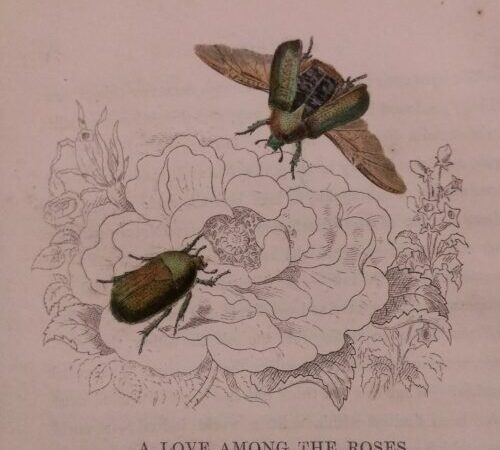

6. Episodes of Insect Life by L.M. Budgen, 1849 – 1851.

Little is known about the life of British author/illustrator L.M. Budgen, who published under the name Acheta Domestica (the scientific name for the house cricket). Like her better-known contemporary J.J. Grandville, she created whimsical drawings of insects. Unlike Grandville, however, her emphasis was on entomology, the actual study of insects, rather than simply using their likenesses to create satirical caricatures of people. This difference is borne out in her attention to anatomical detail and the amount of scientific information included in her books, most notably in the three-part series, Episodes of Insect Life. Cognizant of her intended audience, however, Budgen’s books were anything but dry. In Episodes of Insect Life, gall-flies are “magicians”, antlions “ogres”, and the chapter devoted to plant-eating ‘pests’ is entitled “For Those Who are Not Over-Nice”. Elsewhere, she tells describes the “Jack-o-Lantern in armour” (mole cricket) and “insect dirge-players” (deathwatch beetle). In the words of the entomologist S.R. Schachat, Budgen is an “under-appreciated” figure, one whose engaging work is well worth delving into.

7. The ladies’ flower-garden of ornamental annuals by Jane Loudon, 1840.

After her father’s death in 1827, Jane Loudon found herself wondering how to make a living. Her solution was to write one of the first science fiction novels, titled The Mummy!: Or a Tale of the Twenty-Second Century. The book did remarkably well, and is still in print today. After marrying the editor of a gardening magazine, Loudon turned her energies toward horticulture. Gardening manuals of the time were highly technical, and so Loudon set about creating horticulture guides that would be accessible to regular people. She honed her artistic talents as well, and became a well-respected botanical illustrator. Her work paved the way for gardening to become an activity that nineteenth century women could enjoy.

Read more about the campaign here: https://siarchives.si.edu/blog/celebrating-women%27s-history-month-hernaturalhistory

Posts contributed by McGill Liaison Librarians Elis Ing and Lauren Williams

Campagne sur les médias sociaux Her Natural History : mettre en valeur la contribution féminine à la recherche sur la biodiversité

Collecte de spécimens, illustration scientifique, direction et publication de recherches, rédaction d’ouvrages sur l’histoire naturelle… Voilà autant de domaines où les femmes ont surmonté nombre d’obstacles sociaux et culturels et transcendé la barrière des sexes pour approfondir notre compréhension du monde naturel. Rapport de la campagne #HerNaturalHistory de la Biodiversity Heritage Library (Bibliothèque de la biodiversité patrimoniale), 2019

Le printemps dernier, le service Livres rares et collections spécialisées a participé à Her Natural History, une campagne internationale menée par la Biodiversity Heritage Library qui vise à mettre en valeur le rôle joué par les femmes dans l’histoire naturelle. Les articles proposés ci-après brossent le portrait de femmes fortes et persévérantes qui ont laissé leur marque dans la poursuite de leurs passions. C’est celle de femmes qui ont triomphé en des temps difficiles, et, plus fortes que jamais, ont amélioré leur vie et celle de leurs collectivités. Nous espérons qu’elle vous inspirera tout autant.

1. 121 Paintings of Indian birds, Elizabeth Gwillim, 1801-1807.

Le mari d’Elizabeth Gwillim, Sir Henry, est juge en Grande-Bretagne, le pays natal du couple. Pendant le régime colonial britannique en Inde, on l’affecte à Madras (aujourd’hui Chennai) pour y siéger à la Cour suprême. Lady Gwillim est impatiente d’explorer son nouveau milieu, d’apprendre à connaître le peuple indien et ses coutumes, ainsi que de profiter des paysages et des animaux singuliers qu’elle peut observer du seuil de sa porte. Comme la plupart des femmes de la bourgeoisie à l’époque, elle a suivi des cours de peinture toute sa jeunesse. Elle décide de mettre son art en pratique et part dans la jungle pour peindre autant d’oiseaux que possible. Suscitant les éloges d’ornithologues contemporains pour leur justesse scientifique, ses tableaux ont récemment fait l’objet de nombre de projets de recherche passionnants. Et si Audubon est souvent reconnu comme le premier artiste à avoir peint des portraits d’oiseaux grandeur nature, Lady Gwillim le devance de 30 ans.

2. The Boys and Girls’ Illustrated Bird Book, Julia Colman, 1857.

Julia Colman (1828-1909) est la directrice du département de littérature de l’Union chrétienne des femmes pour la tempérance et elle possède un esprit scientifique impressionnant d’efficacité. Avant d’étudier les sciences et les langues étrangères à l’université, elle apprend d’elle-même la botanique et établit sa propre classification de centaines de spécimens. The Boys and Girls’ Illustrated Bird Book est son premier ouvrage, suivi d’autres, ainsi que de nombreux articles et opuscules, la plupart à caractère scientifique.

3. A history of the birds of Europe : including all the species inhabiting the Western Palaearctic Region, Henry Dresser, 1871-1872.

En 1871-1872, Henry Dresser fait paraître son ouvrage, Birds of Europe, en 84 tomes. On y voit de remarquables illustrations des 634 espèces d’oiseaux décrites par Dresser, produites principalement par le réputé artiste-naturaliste J.G. Kuelemans. Par lithographie, Kuelemans réalise le contour sombre de ses illustrations, puis les complète à l’aquarelle. Cependant, il ne produit de la sorte qu’une seule « copie maîtresse » : les 250 000 autres illustrations publiées, qui deviendront les planches du livre, sont peintes à l’aquarelle par des femmes d’ateliers de coloriste. Ainsi, les femmes se basent sur l’original de Kuelemans pour appliquer à la chaîne une couleur aux planches, chacune son tour. Sur la page titre de cette œuvre monumentale, Dresser attribue à Kuelemans les illustrations, mais les noms des femmes coloristes tombent dans l’oubli.

4. Bird World : A Bird Book for Children , J.H. Stickney, 1898.

Jenny H. Stickney (1840-?) est directrice de la Boston Training School for Teachers, ainsi qu’éditrice et auteure à succès; elle est l’une des premières institutrices à se tailler une place dans le monde de l’édition, à une époque où les enseignantes gagnent en nombre dans le système scolaire public. Bird World, tout comme Bird Book, de Colman, adopte un style conversationnel amalgamant poésie, anecdotes et information factuelle, qui témoigne d’une compréhension de l’esprit et des intérêts des enfants.

5. On molecular and microscopic science, Mary Somerville, 1869.

Mary Somerville (1780-1872) est une polymathe écossaise, dont l’un des premiers traités, intitulé On the Connexion of the Physical Sciences, intègre si brillamment les univers des mathématiques, de l’astronomie, de la géologie, de la chimie et de la physique, qu’il devient le manuel du premier programme de sciences de l’Université de Cambridge. Avant cette publication, le terme « homme de science » désigne toute personne dont les recherches appartiennent à l’une de ces disciplines scientifiques. Or, après avoir lu son traité, le professeur William Whewell invente le terme « scientifique », plus convenable pour nommer Somerville. Le mot « scientifique » décrit mieux son travail, non seulement en raison de son sexe, mais aussi vu la nature interdisciplinaire de sa recherche, fait-il valoir.

6. Episodes of Insect Life , L.M. Budgen, 1849-1851.

On sait peu de choses sur la vie de l’auteure/illustratrice britannique L.M. Budgen, qui a écrit sous la plume d’Acheta Domestica (le nom scientifique du grillon domestique). Comme son contemporain plus connu Jean-Jacques Grandville, elle produit des illustrations d’insectes fantaisistes, mais, de son côté, se consacre davantage à l’entomologie, l’étude des insectes, plutôt qu’à la simple caricature zoomorphe. Cette distinction s’illustre par l’attention qu’elle porte aux détails anatomiques et la quantité d’information scientifique dans ses livres, notamment dans la série en trois tomes Episodes of Insect Life. Consciente de son lectorat, néanmoins, Budgen propose des ouvrages tout sauf arides. Dans Episodes of Insect Life, la téphrite gallicole est une « magicienne », le fourmilion un « ogre », et le chapitre voué aux nuisibles insectes phytophages s’intitule « For Those Who are Not Over-Nice » (pour ceux qui ne sont pas trop gentils). Ailleurs, elle emploie les images « Jack-o-Lantern in armour/insecte-citrouille en armure » (courtilière) et « insect dirge-players/funèbre insecte-musicien » (grosse vrillette). Aux dires de l’entomologiste S.R. Schachat, Budgen est un personnage « sous-estimé », dont le travail passionnant mérite d’être étudié.

7. The ladies’ flower-garden of ornamental annuals, Jane Loudon, 1840.

À la mort de son père, en 1827, Jane Loudon se cherche un moyen de subsistance. Sa solution : écrire l’un des premiers romans de science-fiction, intitulé The Mummy!: Or a Tale of the Twenty-Second Century, un livre qui connaît un succès remarquable et qui est toujours vendu à ce jour. Après avoir épousé le rédacteur en chef d’un magazine de jardinage, Loudon se tourne vers l’horticulture. À l’époque, les manuels de jardinage étant très poussés, elle entreprend de produire des guides d’horticulture accessibles au commun des mortels. Perfectionnant aussi ses talents artistiques, elle devient une illustratrice botanique très respectée. Son travail démocratise le jardinage pour la femme du XIXe siècle.

Pour en lire plus sur la campagne :https://siarchives.si.edu/blog/celebrating-women%27s-history-month-hernaturalhistory

Publications fournies par Elis Ing et Lauren Williams, bibliothécaires de liaison de McGill.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.