by Hannah Deskin, Assistant Archivist, McGill ROAAr

As director of the Canadian Geological Survey between the years 1895-1901, George Mercer Dawson laid the groundwork for scientific exploration in some of the most biodiverse regions in the world. A geologist and explorer, Dawson moved to Montréal in 1855 when his father, John William Dawson, became Principal of McGill. The McGill University Archives recently undertook a digitization project to scan and make available a portion of the 11.8 metres of archival material in the Dawson-Harrington Family Fonds. The fonds includes traces of George Mercer Dawson’s contributions to geology and the natural sciences, and is a great departure point for discovery.

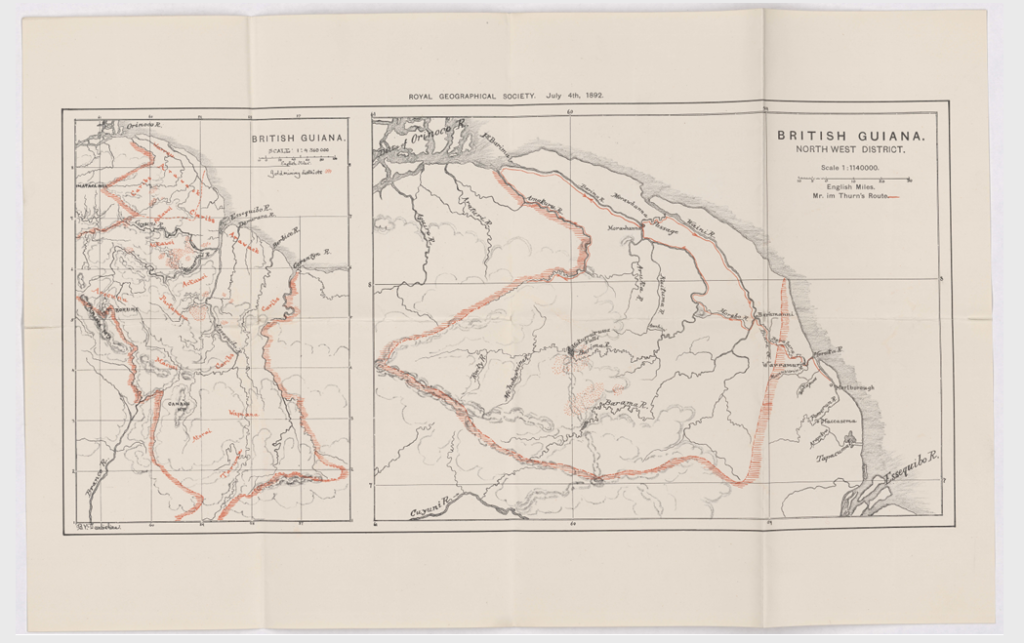

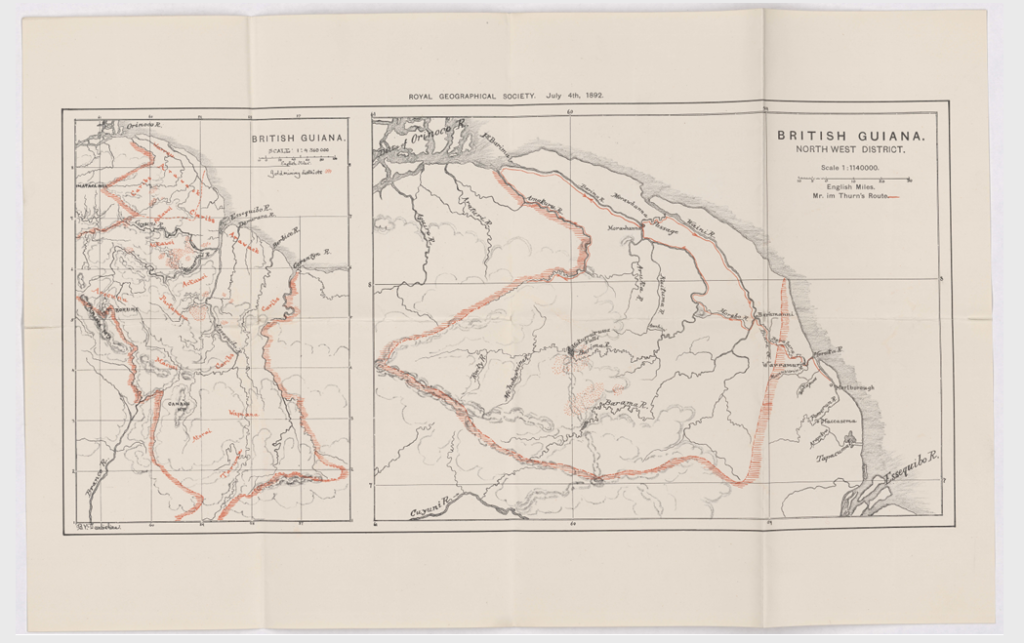

I came across the above map of Guyana produced by George Mercer Dawson between 1881-1892. Guyana’s seemingly endless biodiversity and unique landscape, surveyed and mapped by Dawson, inspires generations of natural scientists to this day. In 2021, biologist Bruce Means is believed to have discovered 3 new species of frogs when he teamed up with National Geographic and mountaineers to ascend a previously unexplored Tepui rock formation in the area. Inspired by Dawson’s map and Means’ discovery, I went look for stories of scientific exploration in this region that McGill’s rare collections might hold.

My curiosity led me to McGill’s collections donated by Dr. Casey Albert Wood. Wood was a contemporary of George Mercer Dawson, and a passionate ophthalmologist and ornithologist, who became an expert in the study of bird vision. Wood was drawn to Guyana some thirty years after Dawson to participate in the region’s active scientific community. In a 1922 letter from Georgetown, Wood gives a colourful description of Guyanese biodiversity following a stay at a jungle field-station: “Visualize the toucans and toucanets. One thinks chiefly of their enormous bills, but even these are gorgeously painted in tints that are repeated in their still more brilliant plumage. Then the iridescent macaws… as well as the other highly tinted parrots and parakeets – all of these form but a fraction of the [Guyanese] avifauna.” Wood also bonded with a male Curassow bird (craxis nigra), who he endearingly named Craxy. Dr. Wood wrote in his letter: “[Craxy and I] would often take walks together and afforded much amusement to my associates when they saw this bird, with dignified gait and apparent sense of his importance, strutting along a jungle trail with his solitary human companion.”

Thanks to Wood’s recollections of the creatures he encountered, I re-traced the steps of his scientific groundwork in the region even further back to the artist Peter Paillou, an eminent ‘bird painter’, active in the 18th century. Many of Paillou’s original paintings were purchased by Casey Wood and became a part of McGill’s Blacker-Wood Collection. Serendipitously, Paillou happened to illustrate some of the birds that Wood described in his 1922 letter, giving us vivid visuals to go along with his colourful descriptions. The “highly tinted” birds that Wood mentioned appear in Paillou’s drawing of a Hawk Parrot (Deroptyus accipitrinus, fig 2) and a blue and yellow macaw (Ara aracauna, fig 3). Even a relative of Craxy makes an appearance in Paillou’s work in a depiction of a Great Curassow (Crax rubra, fig 4). Paillou’s work was done primarily from specimens collected and traded in Europe, Wood’ letter shows a growing interest in observing these birds in their natural habitat.

My journey through McGill’s special collections reveals a rich legacy of research to be found in our stacks, bursting with the stories of those who laid the groundwork of scientific research in South America. That said, I leave it to you to forge your own paths of discovery, and in Casey Wood’s own words: “And now it is time to say farewell to both South America and to you; and if we three [ever] meet again, I hope [we have] a good gossip about the “things that are.”

Letter from Georgetown, British Guiana, February 22, 1922. Casey A. Wood, 1922. McGill Rare Books and Special Collections, MSG 1203 (1203-2-2).

Surtout, ne pas perdre la carte! Des chercheurs sur le terrain en Guyane

Hannah Deskin, archiviste adjointe, Bibliothèque des livres rares et collections spécialisées de l’Université McGill

En qualité de directeur de la Commission géologique du Canada de 1895 à 1901, George Mercer Dawson a jeté les bases de l’exploration scientifique de certaines des régions du monde les plus diversifiées. Géologue et explorateur, Dawson déménage à Montréal en 1855 quand son père, John William Dawson, devient principal de l’Université McGill. Dernièrement, les Archives de McGill ont amorcé un projet de numérisation d’une part des 11,8 mètres de matériel archivistique de la famille Dawson-Harrington. Le fonds recèle des traces des apports de George Mercer Dawson à la géologie et aux sciences naturelles et représente un excellent point de départ vers la découverte.

Je suis tombée sur la carte ci-dessus de la Guyane qu’a produite George Mercer Dawson entre 1881 et 1892 (fig. 1). La biodiversité apparemment infinie et le paysage uniques de la Guyane, que Dawson a arpentée et cartographiée, inspirent encore à ce jour des générations de naturalistes. En 2021, on croit que le biologiste Bruce Means aurait découvert trois nouvelles espèces de grenouilles quand il a formé une équipe avec le National Geographic et des montagnards pour gravir une formation rocheuse inexplorée, un tepuy, de la région. Inspirée par la carte de Dawson et la découverte de Means, je me suis mise à la recherche d’histoires d’explorations scientifiques de la région que pourraient contenir les collections rares de McGill.

Ma curiosité m’a menée aux collections de McGill qu’a données le Dr Casey Albert Wood, contemporain de George Mercer Dawson, ophtalmologiste et ornithologue passionné qui devient expert de la vision aviaire. La Guyane attire Wood quelque trente ans après Dawson qui rallie la communauté scientifique active de la région. Dans une lettre datée de 1922 en provenance de Georgetown, Wood rédige une description colorée de la biodiversité guyanaise au terme d’un séjour dans une station sise dans la jungle : « Imagine les toucans et les toucanets. On songe surtout à leurs énormes becs, mais même cet attribut, aux teintes magnifiques, se répète dans un plumage encore plus brillant. Et il y a les aras iridescents… de même que les autres perroquets hauts en couleur qui ne forment qu’une fraction de la faune aviaire [guyanaise]. » Et Wood se lie à un hocco mâle (cracidae), qu’il baptise affectueusement Craxy. Le Dr Wood écrit : « [Craxy et moi] partons souvent en promenade, ce qui a amusé mes collègues à la vue de cet oiseau à la démarche altière et apparemment imbu de son importance qui se pavanait dans une piste de la jungle aux côtés de son compagnon humain solitaire. »

Grâce aux souvenirs qu’a conservés Wood des créatures qu’il a croisées, j’ai retracé les étapes de son travail scientifique dans la région à même le travail de l’artiste Peter Paillou, éminent « peintre aviaire » en activité au XVIIIe siècle. Casey Wood acquiert nombre des œuvres originales de Paillou qui sont assimilées à la Collection Blacker-Wood de McGill. Par un heureux hasard, Paillou avait illustré certains des oiseaux que Wood décrit dans sa lettre de 1922, de sorte que nous avons des images éclatantes pour accompagner ces descriptions colorées. Les oiseaux aux « couleurs vives » que Wood mentionne se retrouvent dans le dessin que Paillou fait du papegeai maillé (Deroptyus accipitrinus, fig. 2) et d’un ara bleu et jaune (Ara aracauna, fig. 3). Même un hocco parent figure dans une description que fait Paillou du grand hocco (Crax rubra, fig. 4). Le travail de Paillou portait surtout sur des spécimens collectionnés et vendus en Europe et la lettre de Wood laisse transparaître l’intérêt croissant à l’endroit de l’observation de ces oiseaux dans leur habitat naturel.

Mon séjour dans les collections spécialisées de McGill révèle un riche héritage de recherches dissimulées dans nos piles où fourmillent les histoires de ceux qui ont jeté les bases de la recherche scientifique en Amérique du Sud. Cela dit, je vous laisse tracer vos propres voies vers la découverte et, pour reprendre les mots de Casey Wood : « Il est maintenant temps de dire adieu à l’Amérique du Sud et, si [jamais] nous nous revoyons, j’espère [que nous aurons] une bonne conversation sur l’« état des choses ».

Letter from Georgetown, British Guiana, February 22, 1922. Casey A. Wood, 1922. McGill Rare Books and Special Collections, MSG 1203 (1203-2-2).

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.