La version française suit

By Frédéric Giuliano, Archivist, McGill University Archives

“The times were rife with great men making great strides, but in truth, I felt like one of those frogs in my adolescent poem, most certainly the younger, lifted from his own comfortable pond into one so much larger, where the bullfrogs reigned, massive and sure of their place on the largest pad. I knew mental fear, but swore too that when I came back again to Montreal I would be taller in mind, as tall as any other man of science.” – George Mercer Dawson, 1869 [1]

Cabinet card of George Mercer Dawson, 1885

Photographer: William James Topley

McGill University Archives

Frank Dawson Adams fonds (MG 1014)

PR029133

These are the words of the young, 4 foot – 8 inch, George Mercer Dawson when mounting the ramp of the ship that was to carry him to the Royal School of Mines in London. It was 1869, and London was the centre of the world. After three years in London, George would come back to Montreal and prepare for his work at the North American Boundary Commission (1872-1874). He was responsible for surveying territory that had been a subject of many disputes since the Treaty of Paris of 1783 – the border between the province of Manitoba and the state of Minnesota that passes through the Lake of the Woods. That delicate work would establish his reputation as a highly respected geologist and surveyor.

From there, Dawson would go on to make one of the most epic exploratory journeys in Canadian history. Dawson is known to be the first educated man to explore and map the Yukon. Dawson City is named in his honour. Although he was primarily interested in what was beneath his feet, extensive correspondence shows that he captured the interest of those he interacted with as well. He was given the name Skookum Tumtum, “brave cheery man”, by the Cree, a First Nations community he met while studying the Lake of the Woods region.[2] Letters, journals and other items in McGill’s Dawson-Harrington family fonds note his courage and boundless enthusiasm despite his physical weakness and illness. At the age of 11, Dawson was afflicted by tuberculosis of the spine resulting in a deformed back and stunted growth.

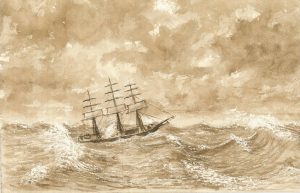

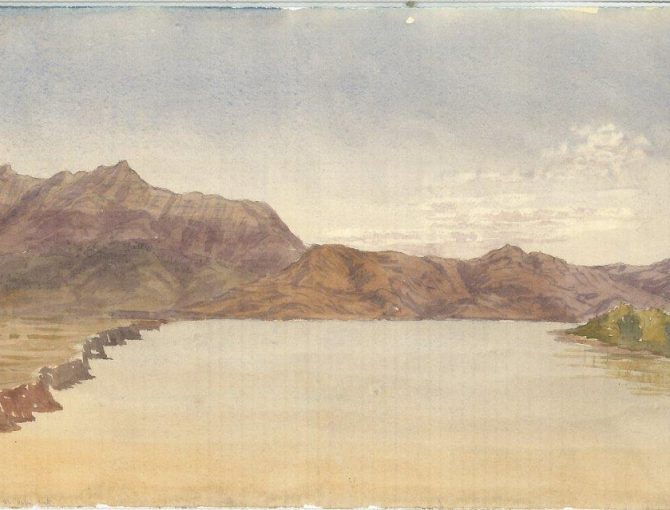

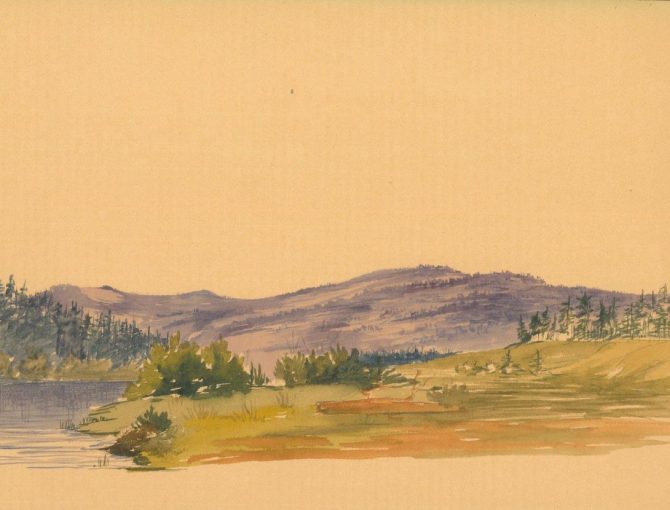

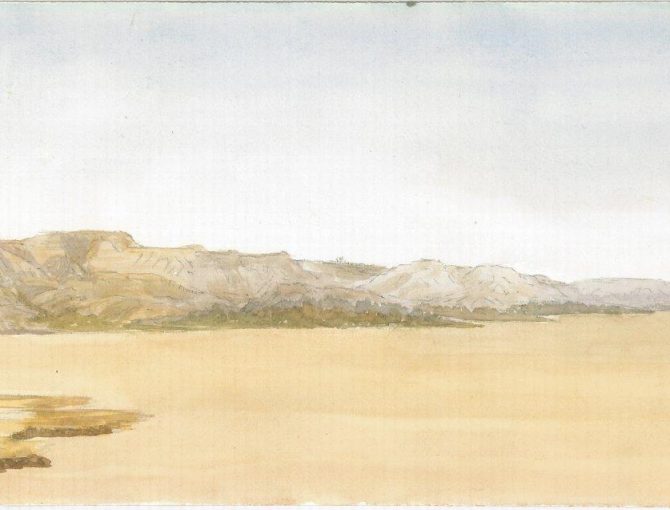

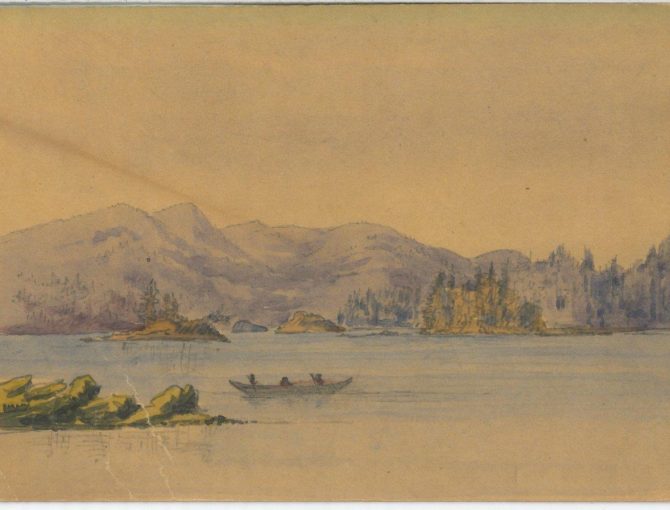

Lake Erie ship. George Mercer Dawson. 1869. McGill University Archives, Dawson-Harrington family fonds.

After all his travels, this ship, Lake Erie, remained of great importance to George, as numerous sketches of it illustrate. This particular illustration shows the ship jostled by the waves when a storm engulfed Dawson’s crew for three days while passing the Gulf of Saint Lawrence. If George were still alive today, would he see this sketch and his other drawings as a symbols of his colourful journey? Of course, we will never have this answer, but it is certainly what comes to mind when scrolling through the slideshow below featuring the vivid work he left for us to uncover.

[1] Phil Jenkins, Beneath my feet: the memoirs of George Mercer Dawson., Toronto: McClelland & Stewart Ltd. 2007, p.36.

[2] Joyce C. Barkhouse, George Dawson the little giant. Toronto/Vancouver: Clarke, Irwin&Company Limited. 1974, p. 74-87

Le parcours haut en couleurs de George Mercer Dawson

Par Frédéric Giuliano, archiviste, Archives de l’Université McGill

« C’était une époque foisonnante, où de grands hommes réalisaient de grands projets, mais en vérité, j’avais l’impression d’être une des grenouilles du poème de mon adolescence, très certainement la plus jeune d’entre elles, arrachée à son étang rassurant et jetée dans un autre beaucoup plus grand où régnaient les ouaouarons, énormes et persuadés de leur droit de cité. La peur a habité mon esprit, mais me suis juré que je reviendrais à Montréal grandi mentalement, aussi grand que n’importe quel autre homme de science. » – George Mercer Dawson, 1869 [1]

Photographie de format cabinet de George Mercer Dawson, 1885

Photographe : William James Topley

Archives de l’Université McGill

Fonds Frank Dawson Adams (MG 1014)

PR029133

Ainsi parlait le jeune George Mercer Dawson du haut de ses 4 pieds 8 pouces (1,42 m), en s’embarquant sur le navire qui allait l’emmener à la Royal School of Mines à Londres. C’était en 1869, et Londres était le centre du monde. De retour à Montréal après trois années passées dans la capitale anglaise, George s’est préparé à travailler pour la Commission des frontières de l’Amérique du Nord (1872-1874), qui l’avait chargé de faire le relevé d’un territoire maintes fois disputé depuis la signature du Traité de Paris en 1783 – la frontière qui sépare le Manitoba du Minnesota en traversant le Lac des Bois. Ce délicat relevé fit de lui un géologue et un arpenteur-géomètre très respecté.

Dawson entreprit ensuite un des voyages d’exploration les plus épiques de l’histoire du Canada. Il est connu pour être le premier homme instruit à avoir exploré et cartographié le Yukon, et c’est en son honneur que la ville de Dawson porte son nom. George Dawson s’intéressait surtout à ce qui se trouvait sous ses pieds, mais son abondante correspondance indique qu’il suscitait également l’intérêt de ceux qu’il rencontrait. Ainsi, pendant son séjour dans la région du Lac des Bois, les membres d’une Première Nation, les Cris, l’ont rebaptisé Skookum Tumtum (« homme brave et joyeux »)[2]. Les lettres, journaux et autres articles conservés à McGill dans le fonds de la famille Dawson-Harrington témoignent de son courage et de son enthousiasme débordant malgré une santé fragile. Dawson souffrait d’une malformation au dos, séquelle d’une tuberculose de l’épine dorsale contractée à l’âge de 11 ans, qui avait freiné sa croissance.

Navire Lake Erie. George Mercer Dawson. 1869. Archives de l’Université McGill. Fonds Frank Dawson Adams.

Au terme de ses expéditions, George a gardé un souvenir affectueux du navire Lake Erie, dont il a fait de nombreux croquis. Sur cette illustration, les vagues secouent le bateau pris dans un orage pendant trois jours dans le golfe du Saint-Laurent. Si George était encore parmi nous, dirait-il que ses œuvres symbolisent sa vie haute en couleurs? Nous ne le saurons jamais. Par contre, en regardant le montage saisissant ci-dessus, c’est difficile d’imaginer autrement.

—

[1] Phil Jenkins, Beneath my feet: the memoirs of George Mercer Dawson., Toronto: McClelland & Stewart Ltd. 2007, p. 36.

[2] Joyce C. Barkhouse, George Dawson the little giant. Toronto/Vancouver: Clarke, Irwin&Company Limited. 1974, p. 74-87.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.