During the winter 2014 semester, the McGill Library welcomed 5 practicum students from the McGill School of Information Studies (SIS). The SIS website outlines the practicum experience as

a 3 credit academic elective course in which master’s-level students participate in field practice under the guidance of site supervisors. Students benefit from the opportunity to apply their theoretical knowledge base and learning in a real-world setting, while gaining experience and practicing professional skills. Site supervisors and their workplaces benefit from the energy, knowledge, and skills of an emerging information professional while providing students with a valuable mentorship experience in a real-world setting.

Library Matters took a practicum pause with all five students to talk about their work at the McGill Library and how their experience may help to inform Library units as they move forward with related projects. The fourth interview features Talia Olshefsky whose practicum responsibilities included creating an inventory of the Library’s extensive map collection, addressing physical storage requirements, and determining appropriate access points. Experimentation with new tools and technologies related geographic information systems (GIS) resulted in the development of innovative ways of discovering this collection, particularly sheet maps of Montreal published in the 50s and 60s.

Library Matters (LM): Tell us a little bit about your background. What made you want to study information studies?

Talia Olshefsky (TO): I feel like it was a long road. Originally I was in Fine Arts – photography. I did a degree at Dalhousie University in Halifax. And after completing that I came to Montreal actually intending to do Art Therapy at Concordia. I changed my mind and then settled into Montreal, decided that I loved it and wanted to stay. And two years ago, I knew I wanted to do a Master’s program. At that point, I had also had experience through Young Canada Works. One summer, I got a job working on an archeological dig. I got the job doing their photographic documentation. Through that, I sort of met a bunch of people who worked at the Nova Scotia museum, and ended up getting hired back a few years in a row to actually do some collections work in their museum. They were really kind to me and trained me so all of a sudden without any really formal education I ended up doing cataloguing and collections work. There I really fell in love with it. While in Montreal, I applied to both SIS and the photographic preservation program at Ryerson. In the end I chose this program because I saw it as being a little more open ended. I had sort of learned enough by that point to know that I didn’t know exactly where I wanted to end up. I knew from my experience at the museum that information management, collection management was really for me, but not necessarily specifically photographic materials. So I chose McGill, not really knowing what I was getting into. That’s how I landed here, and I am really glad I did. I think it took me a while to get a feeling for everything.

LM: Can you briefly describe your practicum?

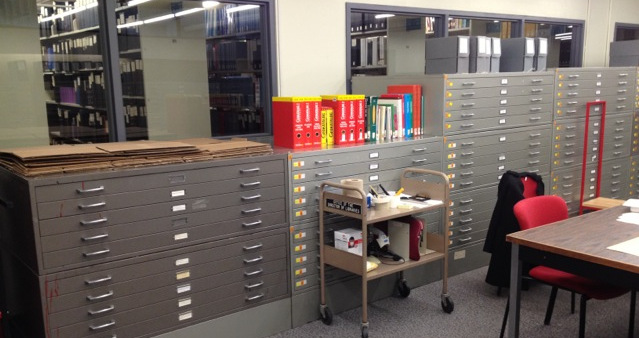

TO: So, two years ago now, the physical paper maps that were in the Burnside Building were moved to the Humanities & Social Sciences Library in order to renovate the former space and turn it into an actual GIC Tech Centre. At that time about half of the maps had physically been moved to the McLennan Library Building. They got put on the second floor and an inventory of the drawers was not taken at that time. The map collection was largely uncatalogued and not organized. My practicum involved figuring out what the plan should be for this material.

So first I had to do an inventory to discover exactly what was there. That ended up being the first half of the project. Then once this was complete, I and my supervisor, Liaison Librarian for Political Science and Map Librarian Deena Yanofsky needed to imagine ways the Library could provide access and make these items accessible.

The first half literally consisted of physically doing a broad inventory of everything in the cabinets. Placement of materials needed to be mapped out, and planning needed to be done in order to reorganize everything. Due to time constraints, I could only do a full inventory of material on one subject so we chose maps of Montreal. We now have a list of all of McGill’s maps of Montreal. Once that was complete, we started to think about visibility and access. So, we had an offer from Web Services Librarian Ed Bilodeau to help us make an online index for the material. The Library had just made one for the William Osler Letter collection. We wanted to just put stuff out there and have it be searchable without having to go through the time consuming process of cataloguing every map and having items listed in the library catalogue. There’s nothing particularly wrong with that, but we didn’t think it would do anything to help publicize the collection.

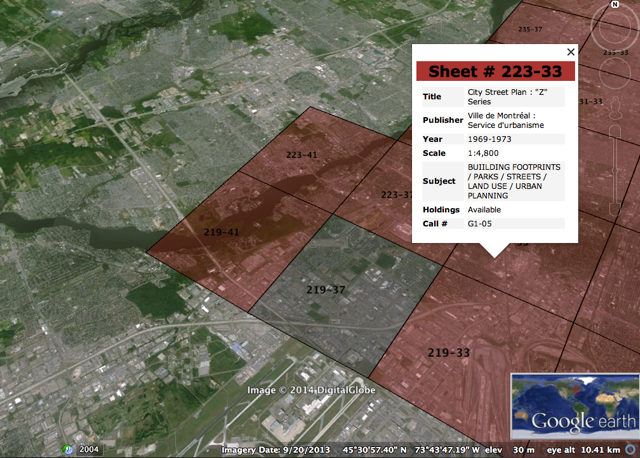

So we went through the process of deciding how the index should be designed and what needed to be included. Outside of that, Deena has some experience with ArcGIS. Through several conversations, we came up with the idea of using ArcGIS to geo-reference some of this material and show people what we had in this collection visually, instead of just be searchable text index. Deena had seen Christopher Thiry, a map librarian at the Colorado School of Mines use ArcGIS to take all of his paper index maps and make actual GIS files out of the shapes. He then geo-referenced this information to create interactive files that people could view and play with in Google Earth.

Snap shot of the digitized map index being browsed in Google Earth, with the metadata for one map sheet displayed.

I didn’t have any experience with ArcGIS but really have always been interested so I jumped at the chance to experiment with that. Christopher Thiry had been really amazing in documenting his process and putting together these lists of instructions for other map librarians. He has all these online instructions for going through this process to build shape files. It’s amazing how much time he took to put it all together. So armed with that and Deena, I jumped. It was actually not so bad. The learning curve was not too awful. Within a few weeks we had figured out how to build these shape files.

LM: At the end of the process, did you get through the entire island of Montreal?

TO: We really didn’t know if we would be successful, or even if we were successful, whether we would have a something that was worth sharing. Our choice was based on what made sense. We only had about ten to fifteen series from the Montreal material that had index maps. There is a set series that was published by the city in the 50s and 60s and these are sort of containable and controllable. They are black and white and depict every footprint of every building in Montreal. They list a lot of really great information like names of businesses and planning data. We picked six series of maps. They all scaled differently. Some series will have fifty maps that cover the whole island, while others include four maps that cover the whole island. Through ArcGIS we also had to build a database that we could attach to that shape file to represent all the metadata for each of the maps. We also chose these maps because they are the most requested series. For example, we met someone at the Library who is doing research on the history of Westmount Square. So she was looking through materials and she wanted to figure out what the footprint of that area looked like in the 50s and the 60s. There are a million reasons people want to see maps.

LM: How many did you do?

TO: In the end we did three. We wanted to start small. It wasn’t too hard to use the software to make the shape and but we encountered lot more complicated things at play than we had predicted. I don’t know much about geography. Many times we made the shape, put it in Google Earth and it was totally wrong. So, with some research and we figured out that the distance between two lines of latitudes really affects projections. This all really took some time to figure out. So we came up with a formula that we could apply to any series for the island of Montreal. Once we did this, it didn’t take more than a few hours to build these shape files. In that way, I think that was the greatest success. We would’ve loved to have said that we completed the series, but it just took too long to figure it out and get there.

So we did three in the end and there are three series of land use maps of Montreal from the 60s. And I really feel confident that with Christopher Thiry’s instructions and our instructions, that anyone would be able to come in and keep going a lot more quickly than we did.

LM: Your practicum was one semester long. Was it enough time to accomplish what you had hoped for?

TO: Yes. Absolutely. In the beginning, the goal for the project was just to complete an inventory because really nobody knew what we had in the collection. Just to have all this information inventoried and organized was our goal. We had to plan the reorganization of these items because right now the room is just by reference only. The Library is still sort of toying with whether they are going to open it up or keep it accessible by reference request. With the planning process done we had enough time to play with ArcGIS a little bit, and so, I think that was a success. We did have enough time to go beyond playing and come out with an end product and so that was really nice.

LM: What skills, lessons and learning moments did you take away from this practicum?

TO: Before arriving here, my only experience was within museums and archives. I had never worked in a library before and I am an archives student. I applied for this practicum because I was really interested in working with the maps. I also was really interested in getting some experience within a library. I think that there’s a lot of possibility that in the future I can see myself working within special collections in a library. I didn’t have too much interest in being at the reference desk or cataloguing. In a lot of ways this practicum was similar to archival work in terms of work flow in that we just had material we had to deal with. It was nice to see how things worked and be able to approach the collection with the idea that it was going to be accessible and usable right away. In archives, materials are also there to be used but it’s a bit of a different approach and a lot of the times you are really just thinking about storage. I am really interested in access. I’ve really become fascinated by the idea of access and ways of publicizing collections.

Deena also encouraged me to apply to a series of different conferences. There are things that I probably wouldn’t have done on my own. I did go through the experience of writing up abstracts and proposals for a few which was really helpful and I’m really glad that I did it. There’s a Canadian Map Libraries conference this summer at Place des Arts so Deena and I are going to present our project, which is great.

LM: What do you wish you would’ve known before starting the practicum?

TO: I think something that was really helpful was that I had an interest in working with the maps. Before knowing that I got the opportunity to do the practicum, I decided to write a research paper for a metadata class I was taking on metadata and maps and map librarianship. This paper was totally unrelated but that was something that in the end really allowed me to come out the gate running and jump into the practicum work a lot faster. I felt like I saw a lot of my peers go through the same thing. I think it was easy to just walk away from a project that wasn’t completed and hard to remember that this was just a practicum.

LM: Did you have an “aha!” moment?

TO: Yes, it was when I had been working with the material long enough to just get past my own learning curve and felt comfortable with it. I started to think about maps and how unique they are. We invest so much time in figuring out how to manage paper maps. We talk about access and visibility, and receive so many requests for data. I had worked with them long enough to maybe fall in love with them a little bit and really just all of a sudden grasp that they had a lot of value. Personally, I love maps. Just spending time with Deena and learning enough about the maps and what they were to start to be able to see the real informational value that they have. And now that I am in more of a position to share that with other people and to talk a little bit more about paper maps and how they are definitely not obsolete – they’re a really neat resource. So, to really get to learn a lot about them from someone like Deena and all of a sudden have a moment seeing all of the information that they contained that was really nice.

LM: What are you going to do with all this work?

TO: Google Earth is a free downloadable app. But they also publish a code for a widget, which is Google Earth, but instead of being its own app that pops up, you can embed it in any website. So with Ed’s searchable online index, you could go to the Library’s page for paper maps of Montreal and when search results come up for maps, you can click on them right there and the index appears and can be interactively browsed right there on the page. And that’s the plan – we want for it to be front and centre on the website. There are similar things on the web right now in terms of geo-spacial data but the way that this information gets accessed is quite difficult. It is hard to find without a searchable index. There are also lots of steps like when you find this information, you download it, and then you still have upload Google Earth. For those used to using computers, and doing research, it’s not a huge deal, but I think that it is a huge deal for a lot of users. So ultimately on the library’s page there will just be a link to the maps page and everything would be there – all in one spot. And then one aspect of the Google widget we are working on is to embed the email right there to. So that when people want to make a map request not only can you zoom in and find what you’re looking for and click on it but when you do click on it, it’s going to open Deena’s email address and immediately send a request to her that you want to see this map. It embeds all the information for you, so Deena knows exactly which one is being requested and there’s no time spent rooting around.

LM: How many maps of Montreal do we have?

TO: About 2,500. It’s really small, like 3-5% of the collection. We have over 120,000 maps in our map collection! I was surprised at the vast amount of materials we have. I knew nothing about the map collection here at McGill before I started. But it’s a lot of international topographical maps. And we were originally the designated holding place, when the government still printed, of each official topographic map of Canada, so we’ve got all that material. The Islamic Studies Library has a map collection and ultimately it would be so wonderful to do sort of a collection management, just sort of amalgamating them and having them all online in the same searchable location. I just never knew that they were there. And if I don’t know, I’m sure a lot of people don’t know either.

LM: What was the feedback like from Library staff?

TO: I did get good feedback. I feel like I had an extremely positive experience. It’s really made a difference. My perspective on the program has changed because of this practicum. There have been a lot of highs and lows. This hands-on experience was a high point. That’s what’s so nice about the idea of a practicum. Even if it had been a summer job, it would’ve been a little harder to get away with experimenting and taking three weeks to just see what we can do with something. That was a really nice feeling. Deena is wonderful to work with. I really enjoyed getting to learn about maps, and then take it a step further and get a chance to run wild and think about access and publicizing the map collection. I also learned a new skill. It was more than I had hoped for. It was awesome.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.