Q and A with Charlotte Frank, one of the curators of the Library’s current Exhibition, Detecting the Anxious Gaze; The Victorian World in Flux

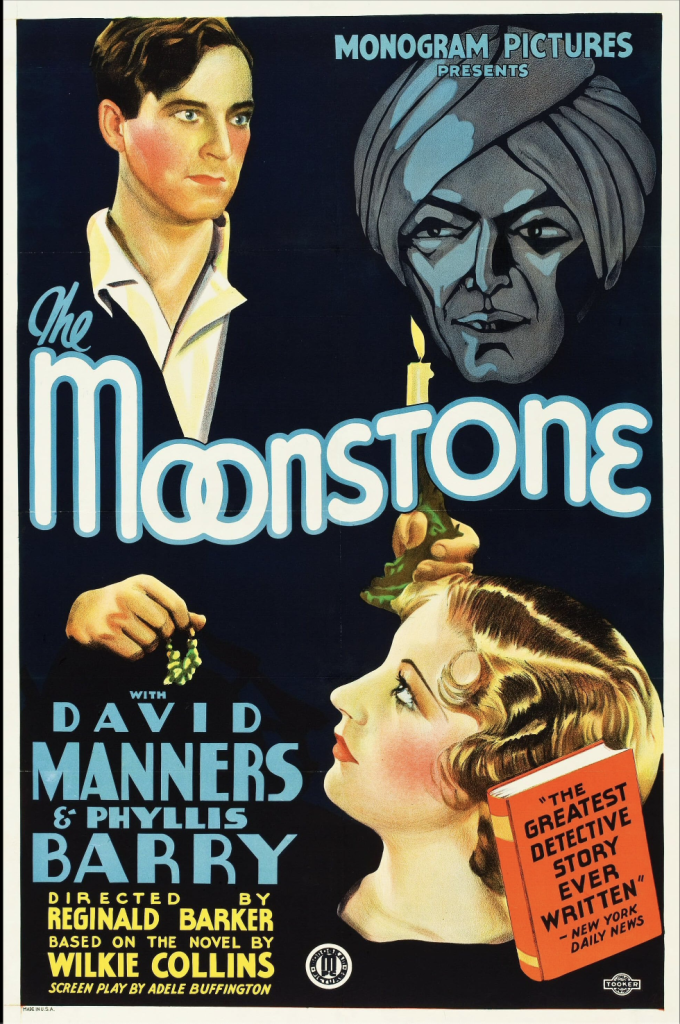

Why did you choose to exhibit the film poster for and film stills from the 1934 adaptation of The Moonstone?

While preparing a presentation and paper on Wilkie Collins’ 1868 novel The Moonstone, I stumbled across this poster for a 1934 adaptation of the film produced by Monogram Pictures – a studio established in 1931 which mainly made low-budget films. Intrigued, I watched this – indeed very low budget – adaptation, which by no means does the novel any justice. In it, large portions of the plot are cut or modified in order to both suit the 1930s setting of the film (the most pronounced distinction from the Victorian original), and its 45 minute format (the novel is around 400 pages). What I came to realize watching Monogram’s Moonstone, is that what is cut or adapted from the novel brings, I think, several of its most interesting elements to light.

How do the poster and two film stills you chose to display illustrate these elements of the novel?

I think the film’s poster illustrates a key feature of the novel, that the film itself leaves out: the ways in which Collins’ novel spoke to Victorian anxieties surrounding colonial encounters. Willkie Collins’ The Moonstone’s plot revolves around the disappearance of an Indian diamond, and the ways in which this foreign object disrupts English domestic order. Critics are divided as to whether the book displays, denounces, or affirms English colonialism – it is difficult to say whether Collins’ depiction of three Brahmans charged with returning the Moonstone to its rightful home in a Hindu temple are meant to inspire fear, suspicion, or admiration. However,any comment upon the relationship between England and India is absent from the film. This may be because of how divided England was in the 1930s on the topic of Indian independence. Instead, the movie’s single Indian character Yandoo (who is not in the novel) has “adopted the Christian faith” and is neither invested in the retrieval of the diamond, nor an outsider to the story’s domestic setting.

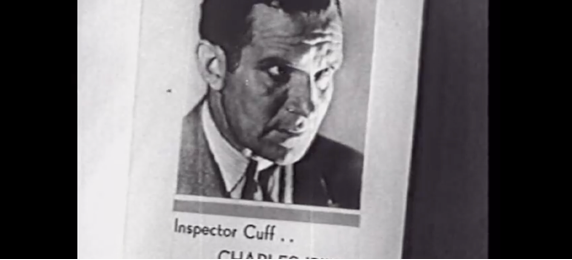

This film still of Inspector Cuff illustrates a second: Collins’ novel is cleverly structured through a series of first-hand accounts which add to the narrative’s mystery and suspense, as different characters’ stories contradict one another, or reveal new information. These rivaling accounts call into question the possibility of arriving at a single, objective truth. The film adaptation of the novel centralizes a single detective called upon to reinstate order, and who is successful in doing so, where his literary counterpart fails.

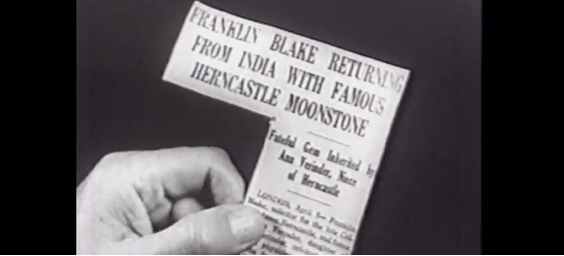

This still of a newspaper clipping points to a third: The newspaper, as an increasingly popular and important source of information in the nineteenth century, was portrayed as potentially unreliable by Victorian authors such as Mary Elizabeth Braddon and Wilkie Collins. In the 1934 adaptation of The Moonstone, however, newspapers convey information straightforwardly, and the veracity of their information is not questioned.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.