Guest contributor: Margaret Carlyle, Ph.D.

U Chicago, Institute on the Formation of Knowledge

2018 recipient, Dr. Edward H. Bensley Osler Library Research Travel Grant

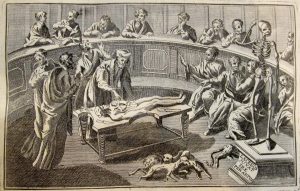

Thomas Rowlandson, “Dr. Wm. Hunter’s Dissecting Room, Windmill St., Haymarket.” Osler Prints Collection, image number OPF000075.

Thomas Rowlandson’s original watercolour drawing of William Hunter’s (1718–1783) London anatomy school on Great Windmill Street captures the multifaceted nature of bodily inquiry in the eighteenth century. It presents the increasingly integrated approach to anatomical research and pedagogy, and especially, the hands-on experience of dissecting for which the school became famous across Europe.

The centre of the image depicts Hunter presiding over an anatomy lesson in which his students are dissecting a male cadaver draped across a table. Paravisual elements provide clues as to who these  students might be. Handwritten on the back of the image are the names of several medical practitioners present, including Hunter’s friend and fellow Scotsman, Tobias Smollett; another Scotsman, the military surgeon, William Cruickshank; and the reputed surgeon, William Hewson. Written in pencil in another hand just below the image title on the front is: “The others were probably [David] Pictairn [sic: Pitcairn], [Matthew] Baillie, Howe & [John] Sheldon. ” In other words, this is an imagined scene that brings together Hunter’s dearest friends, family, and colleagues under one roof.

students might be. Handwritten on the back of the image are the names of several medical practitioners present, including Hunter’s friend and fellow Scotsman, Tobias Smollett; another Scotsman, the military surgeon, William Cruickshank; and the reputed surgeon, William Hewson. Written in pencil in another hand just below the image title on the front is: “The others were probably [David] Pictairn [sic: Pitcairn], [Matthew] Baillie, Howe & [John] Sheldon. ” In other words, this is an imagined scene that brings together Hunter’s dearest friends, family, and colleagues under one roof.

Of these, John Sheldon (1752–1808) warrants a special note. He was a trained surgeon and sometimes lectured at Hunter’s anatomy school. He was also an eccentric whose fascination for the macabre was reported to French audiences by the traveller and naturalist, Barthélemy Faujas de Saint-Fond (1741–1819), following his sojourn in Britain. Saint-Fond was transfixed by the embalmed body he encountered on display in Sheldon’s home, which he described as:

a type of mummy, remarkable in two respects; first, by the subject […] and second, by the remarkable cares and procedures undertaken in its preparation […] the mummy occupies pride of place in the room where the celebrated anatomist, who infinitely adores this subject, normally sleeps. (Barthélemy Faujas de Saint-Fond, Voyage en Angleterre, en Écosse, et aux Iles Hébrides (Paris: Chez H.J. Jansen, 1797), tome 1, 50)

As it happened, the beautiful female subject with brown hair was Sheldon’s mistress whom he had enshrined “in a state of nudity, laid down and sleeping as if on a bed” on an elegant oblong mahogany table positioned in the centre of the room under a glass frame. If nothing else, Saint-Fond was shocked by her remarkable state of preservation, noting her unseemly supple arms, elastic breasts, and glowing cheeks. Sheldon had prepared the mummy using a laborious process of injections and skin tanning, with the assistance of submerging spirits. He had then laid the prepared corpse to rest for five years in a juniper box lined with a calcinated chock designed to absorb humidity. (Ibid., 52)

Sheldon’s ‘mistress mummy,’ as she might be called, is not present here, but there is another cadaver. To the right of the central anatomy lesson is another tabletop dissection of a corpse. The seated figure is engaging with the middle venter of the corpse, while the man standing to his left appears to be pondering what he sees. The standing figure might be William’s brother John, his long-time collaborator and an accomplished anatomist in his own right. Such an interpretation suggests these are colleagues who are dissecting the cadaver together. Alternatively, this scene could be the depiction of the private anatomy lesson that was increasingly popular in this period—at least, for those, like the potential student seated here, who could afford the fee. This method of intimate, hands-on experience with the cadaver was highly prize and came to be known as the “Paris manner of dissection.”

Sheldon’s ‘mistress mummy,’ as she might be called, is not present here, but there is another cadaver. To the right of the central anatomy lesson is another tabletop dissection of a corpse. The seated figure is engaging with the middle venter of the corpse, while the man standing to his left appears to be pondering what he sees. The standing figure might be William’s brother John, his long-time collaborator and an accomplished anatomist in his own right. Such an interpretation suggests these are colleagues who are dissecting the cadaver together. Alternatively, this scene could be the depiction of the private anatomy lesson that was increasingly popular in this period—at least, for those, like the potential student seated here, who could afford the fee. This method of intimate, hands-on experience with the cadaver was highly prize and came to be known as the “Paris manner of dissection.”

A wash basin in the bottom right corner below the second dissection may have been filled with spirits for rinsing surgical tools—though the objective was not strictly speaking to disinfect them, given this  is the pre-microbial age. Such an interpretation is supported by the two tools, including a saw for cutting through bone, lying on the ground to the right of the basin. Additionally or alternatively, this metal tub may have served as a receptacle for capturing bodily fluids during the dissecting process.

is the pre-microbial age. Such an interpretation is supported by the two tools, including a saw for cutting through bone, lying on the ground to the right of the basin. Additionally or alternatively, this metal tub may have served as a receptacle for capturing bodily fluids during the dissecting process.

Several posters are hanging above this two-man dissecting scenario. The poster to the immediate right indicates “Prices for Bodys,” which no doubt serves as a reminder of the difficulty faced by anatomists like Hunter in procuring cadavers for dissection. Body snatchers, or ‘resurrectionists,’ as they came to be known, illicitly obtained cadavers from graveyards before selling them to local surgeons’ colleges. Trafficking in bodies was also a semi-official part of the ritual of the public execution, with the expectation that the surgeon offering the highest fee would be able to make off with the fresh corpse for imminent dissection. The reference to “prices” in this poster also tells us that the human body had achieved a new and potentially morally compromising status as a commodity of the increasingly regulated medical marketplace.

Anatomists like William Hunter would not have been directly involved in obtaining bodies at executions or otherwise, not only because he had many other duties to perform, but also because body snatching was frowned upon in this period. The social profile of the anatomist brings us to the wall poster to the far left, which reads: “Rules to be observed by Gentlemen who dissect.” This guideline highlights the aspirational nature of Hunter’s school: to normalize the dissection of bodies as part of enlightened, gentlemanly science in an age when polite sociability was an integral part of professional practice. And indeed, observing gentlemanly etiquette reflected on the anatomist’s credibility in making new claims about the body and its place in the larger natural world.

Anatomy was nonetheless a gruesome, messy business, which might explain the absence of genteel women from this scene, as well as the presence of touches of satire that the draughtsman, Thomas Rowlandson, infuses throughout. From the smiling cadaver at centre stage to the grin of the pair of skeletons lurking to the left, the scene is not without a sense of unease with—if not outright critique of—anatomy as a discipline worthy of gentlemanly pursuit. The scene may also be a satire of the brand of chaos and spectacle that some social commentators believed to have overtaken London around mid-century.

The human skeletons pictured in front to the left and in back to the right were omnipresent ‘figures’ in dissecting theatres in this period and had been since at least the Renaissance period. The  skeleton-as-teaching-prop was no doubt the innovation of the great sixteenth-century Flemish anatomist, Andreas Vesalius, who was known to carry his real articulated human skeleton from lecture to lecture. There are also animal skeletons in this image dangling from the rafters to the right. The cohabitation of both human and other animal skeletons in this space reveals the growing interest in studying comparative osteology. That is, the science of comparing both male and female human skeletons with a view to charting their differences, and to comparing the bones of humans to those of other animals, in order to enhance knowledge of the human in the great chain of being and to better understand their relationship to each other, as parts of the animal kingdom.

skeleton-as-teaching-prop was no doubt the innovation of the great sixteenth-century Flemish anatomist, Andreas Vesalius, who was known to carry his real articulated human skeleton from lecture to lecture. There are also animal skeletons in this image dangling from the rafters to the right. The cohabitation of both human and other animal skeletons in this space reveals the growing interest in studying comparative osteology. That is, the science of comparing both male and female human skeletons with a view to charting their differences, and to comparing the bones of humans to those of other animals, in order to enhance knowledge of the human in the great chain of being and to better understand their relationship to each other, as parts of the animal kingdom.

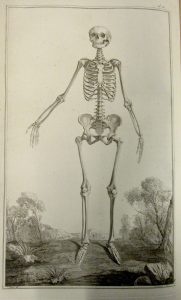

In the first case, the female skeleton depicted in Mme Thiroux d’Arconville’s Traité d’Ostéologie (1759) is indicative of the impulse in this, the Enlightenment period, to ‘gender’ the human skeleton, with the attending ideological goal of tying features of human anatomy to one’s ‘destiny’ in the social realm. Studies of women’s accentuated hip-to-waist ratio and allegedly smaller crania, like the female skeleton presented here, meant that women were perfectly suited to assume the domestic role of child bearing and motherhood, while keeping out of apparently more cerebral activities, like politics and business. The

naturalization of sex differences using human osteology as a starting point may have entrenched cultural perceptions of women’s roles as mothers. The study of the specificity of the female body nonetheless allowed new branches of anatomy to flourish. In particular, William Hunter’s dissections of pregnant patients who had died in or before childbirth allowed him to capture in haunting detail the development of the foetus in utero. His Anatomia Uteri Humani Gravidi Tabulis (1774) provides an almost x-ray vision of the gravid uterus in detailed naturalistic engravings.

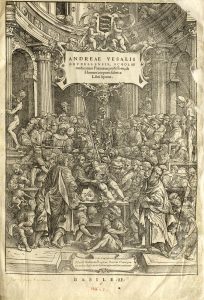

In the second case, the seeds for comparative human-animal anatomy evidenced in this eighteenth-century image were sewn in the time of Vesalius. The lavish frontispiece of Vesalius’ magnum opus, De humani corporis fabrica libri septem (1543), depicts, among other novelties, living animals at the foot of the throngs of viewers gazing at the female corpse on the dissecting table. In particular, the Barbary ape to the bottom left of this image sheds light on the prohibitions against human dissections in Vesalius’ time and his attempts to dissect animals like apes with a view to better understanding humans by way of analogy. The presence of dogs in dissecting rooms—whether for dissection, vivisection, or as domestic companions to anatomists—can be seen in both Vesalius’ frontispiece (see bottom right corner) and that of his contemporary, the celebrated Bartholomeo Eustachi’s Tabulae Anatomicae (Osler edition, 1769).

Detail from the frontispiece, Bartholomeo Eustaci, Tabulae Anatomicae, 1769.

Credit: Margaret Carlyle

Returning to Rowlandson’s watercolour, below the pair of skeletons in the bottom left of the image is an aproned dissector removing the entrails from a recently obtained cadaver. Given the problem of putrefaction in the absence of modern-day refrigeration, the turnaround time for dissecting was brief, with winter months being most favourable for more extensive studies of the corpse. However, this was no obstacle for William Hunter, who ensured a steady supply of fresh corpses for students to dissect with their own hands. For this reason alone, he is considered a pioneering teacher of human anatomy.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.