by Ronny Litvack-Katzman, Research Assistant, ROAAr

“A whole romance contained in four little lines”, “seven words [that] gave a three volume novel in a nutshell” — such are the descriptions that 19th-century commentators gave to the collection of personal advertisements known as the Agony Column. Found on the front page of daily Victorian newspapers, the column published individual, largely anonymous contributions sent in by writers from across the British Empire. Though the Agony Column took its name in the early 1850s from the numerous complaints and indiscretions voiced within, over the course of the latter 19th-century it evolved into a public forum for Victorian citizens to communicate with family and friends and, in some cases, engage in clandestine and cryptic correspondences. Typically a few dozen words in length, the agony ads were read by lovers, criminals, students, and entertainment seekers alike.

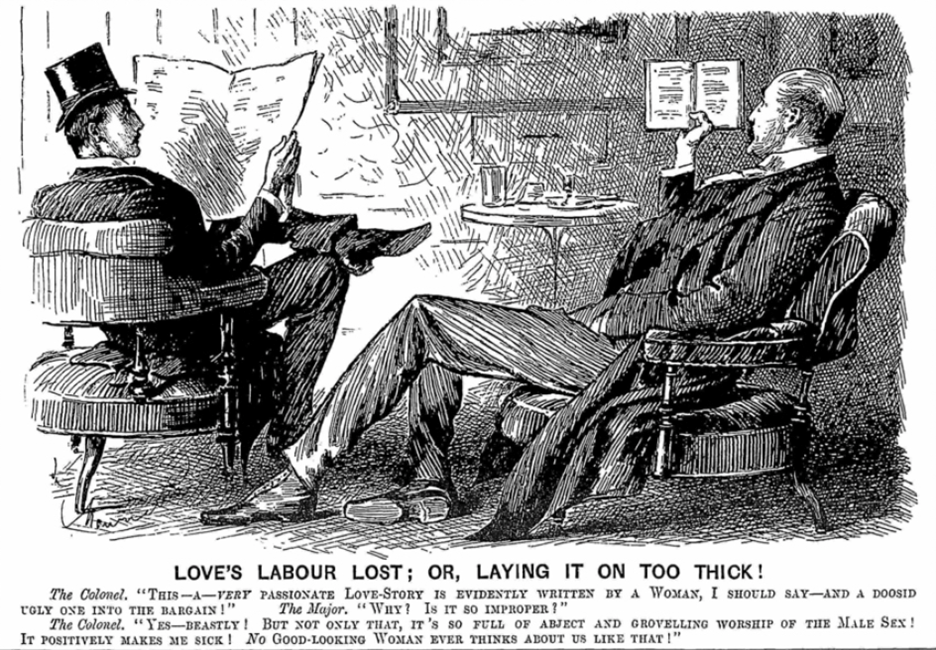

In some shape or form, personal advertisements existed in British newspapers since the advent of the newspaper itself. It was not until the Victorian era, however, that newspaper readership began to rise in earnest. As the number of general readers increased, so too came a rise in the readership of the Agony Column. In the heyday of Victorian newsprint, between the mid-1850s and late-1890s, agony ads were all the rage, making appearances in other forms of popular media entertainment, most notably the ever-popular Victorian novel.

Using the Gale Digital Scholar Lab, researchers working at the McGill Library can access a complete digitized archive of The Times’ Agony Columns dating back to the late 18th-century.

Quite literally front-page news, the Agony Column was read by the vast majority of British citizens across the class spectrum, from Queen Victoria to her subjects. Noting the popularity of the column, editors, such as those as the widely read Times, placed the advertisements on the cover of the newspaper, second only to shipping information and marriage and death notices. It would not be until well into the latter half of the 20th-century that personal ads were sectioned to the back of the newspaper in favour of pressing current affairs. It is there they can still be found today.

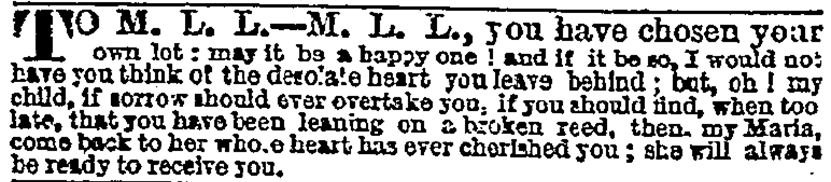

Personal ads ranged widely in character and content, from the mundane to the absurd. The quintessential agony ad correspondence occurred between two or more close individuals, usually involved in amorous, lewd, or criminal situations plagued by peril or the threat of discovery. A typical message, such as the one published in February 1853, addresses “M. L. L.” and is sent by a despondent mother begging her runaway daughter to return home:

Semi-anonymous messages like these fascinated the public, who would monitor subsequent issues in the hope of gaining further detail. Coded advertisements could contain bawdy tales of elopements and criminal activity. Such encrypted ads could include any number of codes, cryptograms, and variations in language to obscure their message or the correspondents’ identities. Although at times hard or even impossible to parse, readers returned to the Agony Column as a daily dose of entertainment and as a means to connect with one another in rapidly changing media environment.

Ciphers of the Times is a SSHRC-funded research project led by Nathalie Cooke, with assistance from Leehu Sigler, that investigates cryptic communication embedded in the Agony Columns of Victorian newspapers and their influence on Victorian society and literature. For updates, follow us on Instagram.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.