A happy cohort of undergraduate students were hired last term to devote their energies to systematically comb through a portion of the stacks in Rare Books and Special Collections in order to stabilize books most in need of protection. Working over several months, this time allowed the opportunity to get acquainted with significant printings and bindings. Most of their conservation work was accomplished on the Cutter Collection, an assemblage of early accessions, encompassing a range of dates, languages and subject matter. Five students have selected a book (or two) and explained in the texts below why it resonated with them. I enjoyed sharing their enthusiasm on these selections – all of the copies are unique in some way. It became clear that the task of item-by-item stabilization was a mutually beneficial book history learning experience. These gems encapsulate the evolution and variety of book production as well as eye-catching binding techniques. They are just a small sampling of the marvellous surprises sitting on our shelves. We hope that you will appreciate these insightful and intimate narratives. – From the editor and student supervisor, Ann Marie Holland

Eden Autmezguine

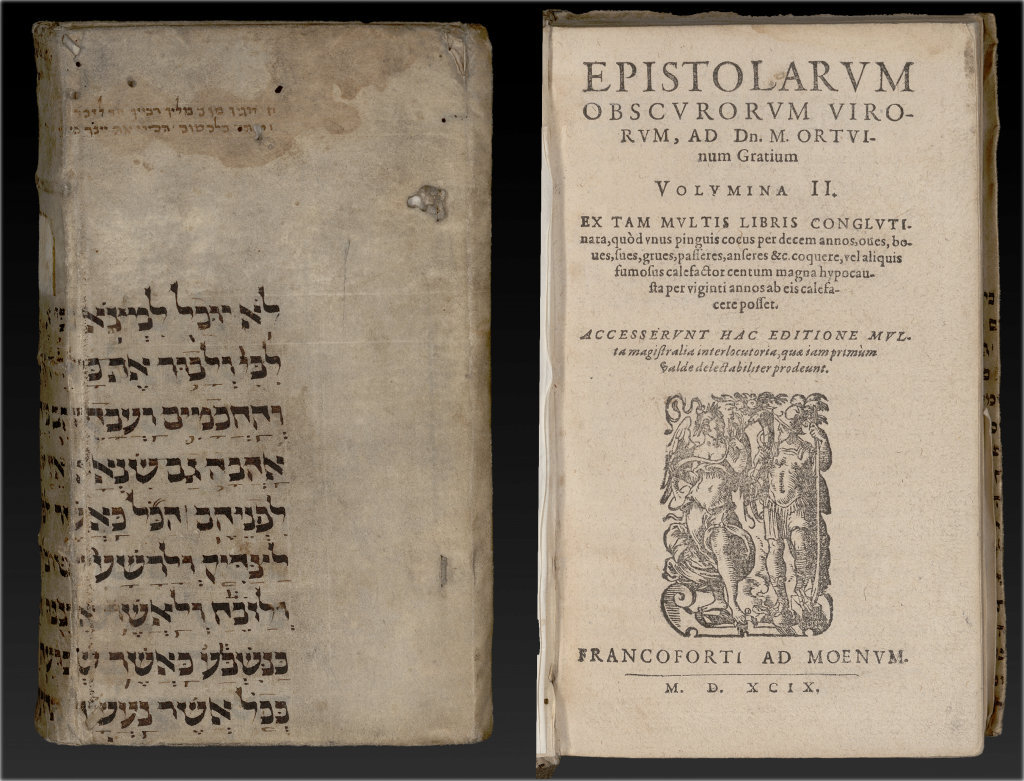

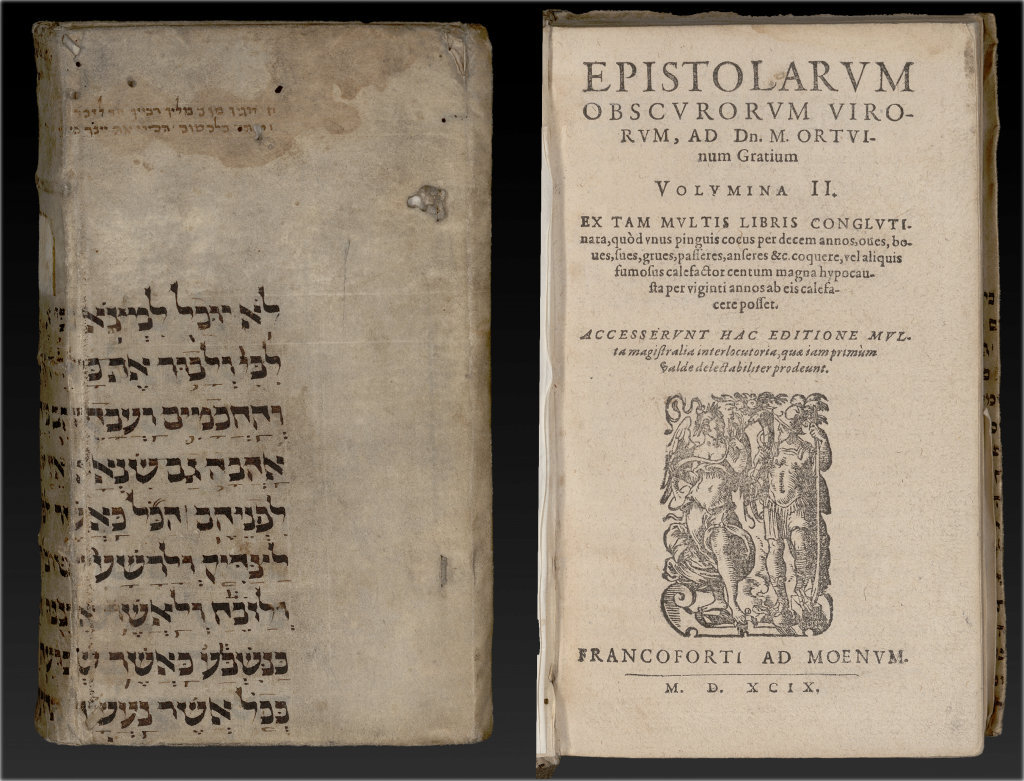

Johannes Crotus Rubeanus (1480-1539).

Epistolae Obscurum Vivorum. (Letters of Obscure Men).

Francoforti ad Moenum:1599. With former manuscript used as covers.

I love stories and anything with a story to tell, even if most of it is lost to time. When I am working on a book, I often find myself wondering about the many hands it has passed through before mine—especially those hands that have brought it into being—and whatever visible traces they may have left behind. Sometimes, these hints make its story both more fascinating and more enigmatic to me, as is the case with this book. It’s written in Latin, and was published in Germany in 1599. Inside, the text is ornamented with decorated woodcut initials and tailpieces. On the front and back covers, faint marks from the pair of ties that once bound it are still visible. The type of binding is limp-bound vellum with overlapped fore-edges, stiffer than a modern-day paperback but more flexible than a hardcover. What makes this book truly special to me, though, is that it is bound with a Hebrew manuscript.

In the Middle Ages, because vellum was both valuable and durable, leaves that had once been books were often kept and reused to bind other books. Additionally, Christians often used materials from Jewish libraries for this purpose. This binding fragment is a leaf from what would have been a larger book. The main column of text, written in a large, beautiful hand, extends from the middle of the front cover to the middle of the back cover. I was able to identify it as a portion of Kohelet (Ecclesiastes), specifically the end of chapter eight and beginning of chapter nine. The ktav (traditional script) is 14th– or 15th– century Ashkenaz, likely German, featuring both the nikud (diacritical marks) and te’amim (cantillation marks). There are masoretic notes in the upper and lower margins. The column of smaller text on the right-hand side of the back cover, of which only a small part is visible, is likely a commentary. Upon careful inspection, faint letter-impressions from the writing on the other side of the page are visible.

Surprisingly, there is some connection between the binding fragment and the book’s contents! Letters of Obscure Men is a collection of satirical letters in support of the German Humanist Johann Reuchlin which mock scholasticism and monasticism, largely by pretending to be written by fanatical Christian theologians who discuss whether all Jewish books should be burned or not. Interestingly, these letters were based on the real-life public disputes between Reuchlin and Johannes Pfefferkorn, a former Jew who converted to Christianity and tried to have all copies of the Talmud destroyed. It is somewhat ironic, then, that this particular volume should have been bound with a fragment of a Jewish book, and in Hebrew no less. (Special thanks to Prof. Deborah Abecassis and Jen Taylor Friedman for their assistance and expertise.)

Jamie Farr

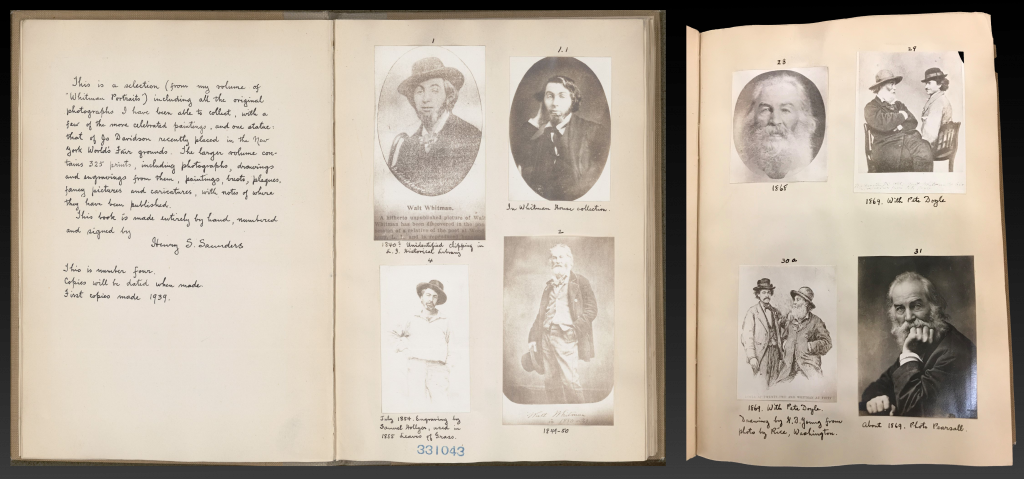

Henry Scholey Saunders (1864-1951).

Whitman Photographs.

Toronto: Henry S. Saunders, 1939. With mounted photographs. Copy no.4 of a limited ed.

Presented to the library by Lady Amy Redpath Roddick.

Something I have discovered working at Rare Books and Special Collections is that the old saying is true: you can never judge a book by its cover. This binding is rather dull – beige and sturdy, holding up impressively well for a book from 1939. The pages are made of cardstock – not typical for books of the era – and the closer you look, more eccentricities begin to reveal themselves. This book by H.S. Saunders is part of a larger collection. Nine volumes comprise the entirety of the collection, containing over 300 items that preserve the clothing, company, and overall spirit of Walt Whitman throughout the course of his life. Each book was made entirely by hand, numbered and signed by Saunders himself. In it, mounted reproductions of portraits, paintings, drawings, and busts of poet Walt Whitman adorn the pages. Turning the pages, it is possible to see the spots where he pasted each picture onto the pages, some askew slightly. Saunders scrawled captions under each of the 100 pictures, sketching out the context of Whitman’s life, which provides unparalleled access into the life of a literary great. Saunders’ dedication to archiving and honoring Whitman is exemplified in his handmade book, and is a deeply moving piece of history to hold in your hands.

It goes without saying that Whitman’s prose transcends time. These photos, however, are grounded in the minutiae of Whitman’s life. Items 28 and 29, are a photo and drawing of Whitman and his longtime partner Peter Doyle. In matching derby hats, they sit next to each other, Doyle’s arm brushing against Whitman’s leg. Though Whitman’s poetry is rife with exploration and appreciation of the male figure, Whitman would die before the turn of the 19th century and queer liberation movements. During his life, Whitman lived under an increasingly strict set of ‘morality’ legislation, policing his relation with Doyle and pushing his queer personal history into the margins. Even Saunders’ own book, compiled years after Whitman’s death, was circulated only amongst a trusted circle of friends. Out of sight and out of mind, the queer spaces that Whitman inhabited are rewritten and forgotten. However, the donation of this book to the Cutter collection by Lady Roddick has allowed this history to claim its place in modern academia. Whitman can now be conceptualized as a poet, and queer man, and (arguably most important) a New Yorker.

Maggie Nielsen

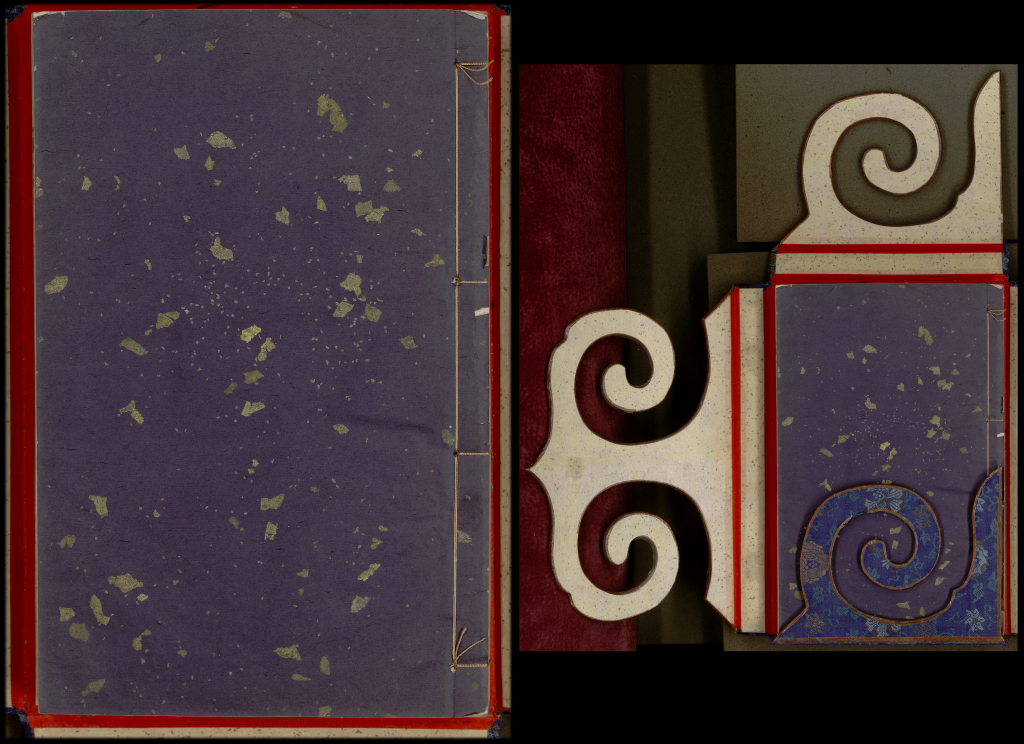

Chiang T’ing Hsi. Active 18th c.

Chinese Encyclopedia. ca. 1716. 2 volumes. With woodcut illustrations, housed in a brocade 4-flap enclosure.

I’ve always been drawn to aesthetics, and find that it’s my most fundamental means of experiencing the world around me. Given this, it’s often unique materiality that catches my eye at Rare Books. I first glimpsed this Chinese Encyclopedia’s blue silk brocade cover from the height of the top shelf. The box opens with great dramatic effect, by way of interlocked swirls, revealing two gold-flecked paper-bound printed book held together by gold thread. A handy inscription inside the box translates the Chinese lettering to explain the set contains two books on the “vegetable kingdom”, as part of an encyclopedia made in 1716 by Imperial order. A careful flip-through shows vertical rows of neat Chinese characters, possibly printed with copper movable type. My favorite part, however, are the illustrations of the various flora. In keeping with Chinese landscape tradition, the delicate lines of these printed illustrations trace the gentle, curving contours and bark patterns of various trees, placed in situ with snatches of scraggly rocks. By means of materiality, this item offers a brief lesson in cultural history, demonstrating not only fine binding techniques and materials, but also an interest in standardizing knowledge in an increasingly modernizing age.

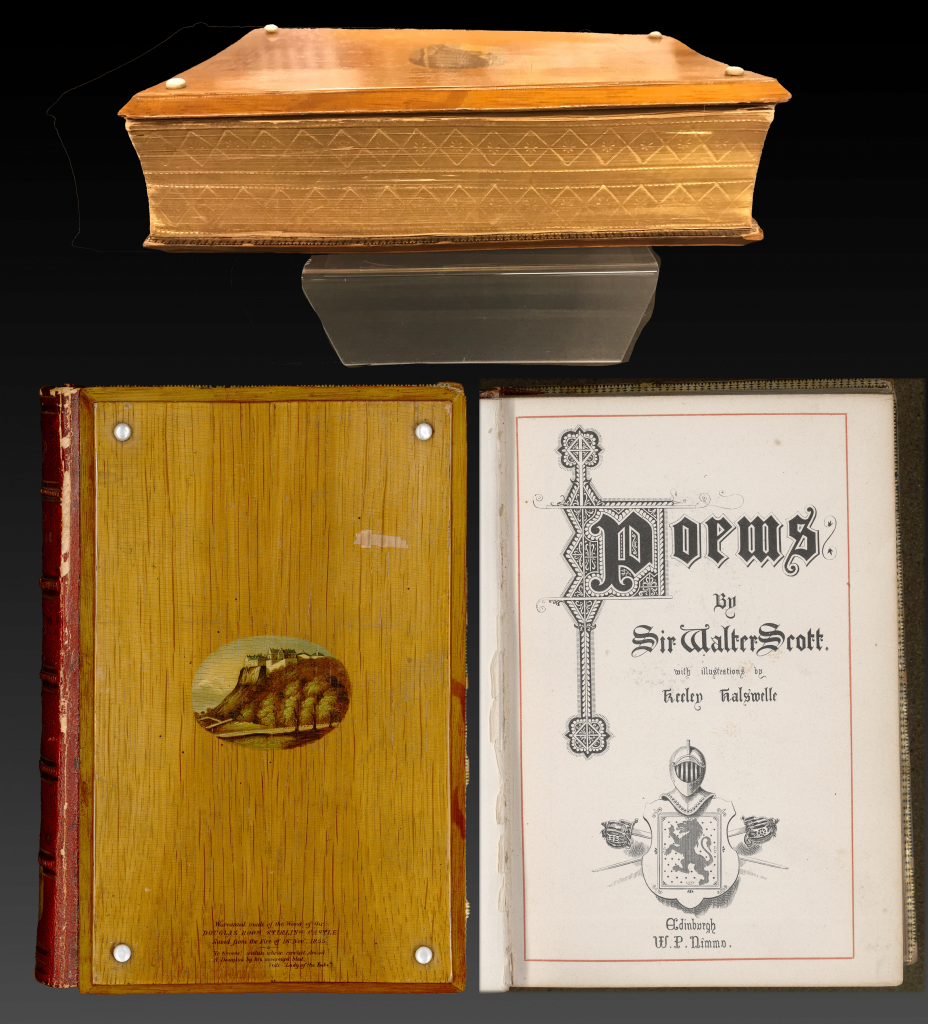

Sir Walter Scott (1771-1832).

Poems of Sir Walter Scott. Edinburgh: W.P. Nimmo, 1861. With bespoke wood covers.

The second book I chose, a collection of poems by Sir Walter John, is a very different example of fine materiality. The back and front covers of the book are a varnished wood embellished by four mother-of-pearl pin-heads at each corner. Centered on the front board is a finely painted miniature of a castle on a bluff overlooking the sea. A small inscription at the bottom of the cover says “made of the wood of the Douglas Room Stirling Castle, saved from the fire of 18th of November, 1855.” This inscription leads me to believe that the unique cover has a significant sentimental value as a vestige of a former home.

Through my time here, I’ve learned to appreciate books as personal items, and this book is a prime example. People collect them, carry them around, bookmark pages, and scribble in the margins. Seeing these sorts of personal micro-histories reflected in the pages’ margins (or their covers) means bearing witness to quotidien marginalia from lives past.

Adrienne Roy

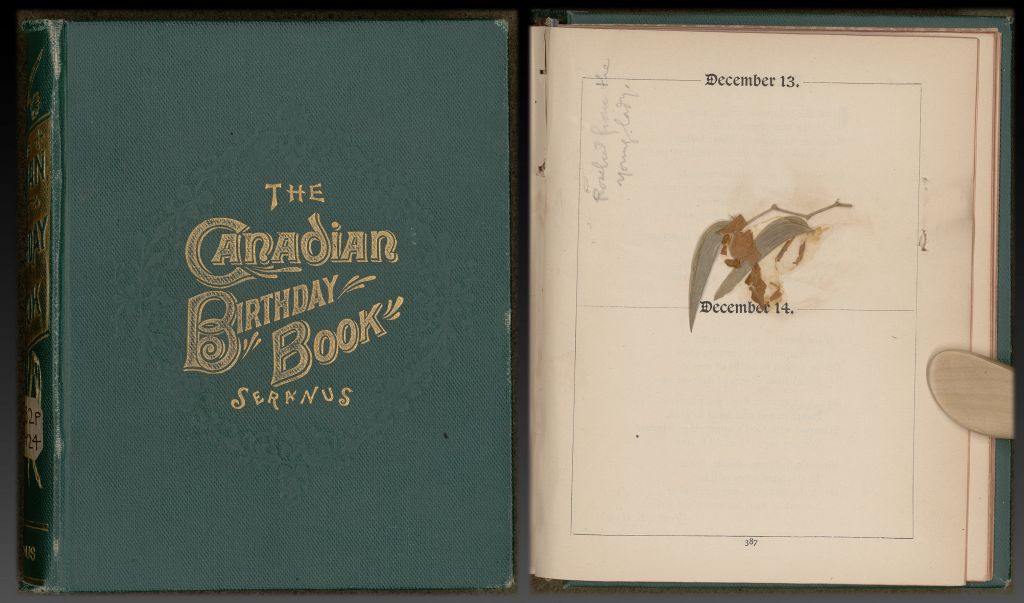

The Canadian Birthday Book. S. Frances Harrison (1859-1935), ed. Toronto: C. Blackett Robinson, 1887.

Presented to the library by W.D. Lighthall (1857-1954).

For better or for worse, I consider myself to be a bona fide Leo. Although I contest the notion that Leos are stereotypically vain — I think we are simply passionate — it’s not particularly surprising that I spotted The Great Canadian Birthday Book with (too much) ease. After a couple of months spent in the East Wing of Rare Books, me and the other students responsible for stabilizing Cutter were starting to get a bit weary, but finding this easter egg in the last row has kept me entertained ever since. Now, whenever I come across the little square book with a dark green binding, I can’t help but open it, re-read my birthday poem, and ask my colleagues when their birthdays are so I can read them their poems too.

Published by C. Blackett Robinson in 1887, The Great Canadian Birthday Book is not an anthology of Canadian poetry, because, as it mentions in the preface, the “necessarily limited space in a Birthday Book would prevent it from achieving that position.” Not only does this treasure chest of Canadian poetry include verses in English and French dating back to 1783, but there is an additional treasure to those who dare to read this book with the seriousness it merits: pressed between the pages of December 13th and 14th is a dried flower, and next to it, a pencil note that reads “A rosebud from the young lady”. Having finished my third year as an English major, I can assure you that my penchant for literature extends beyond birthday-related books. However, one of my favourite things about working in Rare Books has been witnessing the ways that people have loved these items long before I stumbled upon them.

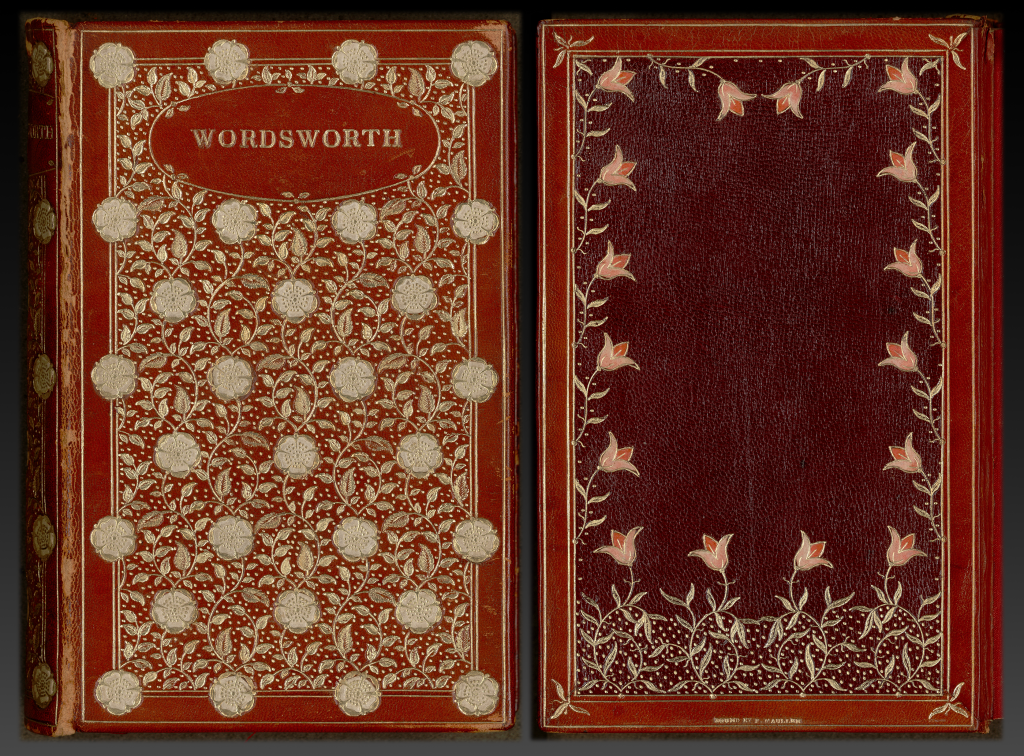

William Wordsworth (1770-1850).

The Poetical Works of William Wordsworth. London: George Routledge and Sons, 1833.

Extra-illustrated, fine binding, signed F. Maullen. A gift of Alice Redpath.

Beyond encountering materials from the world’s most prolific literary figures, one of the most fascinating things about working in Rare Books and Special Collections is coming across beautifully bound books. This copy of The Poetical Works of William Wordsworth spectacularly blends these two elements. Adorned with embossed floral patterning and stamped with gold foil, my colleague made the apt observation that this book would make an elegant gift. Whether it was a gift or not is still a mystery, but the reverse side of the book’s silk flyleaf reveals that it belonged to Alice Redpath, a notable benefactor of McGill Libraries. Her contributions continue to make our shelves much fuller and more ornate, and for that we are so grateful.

Olivia Wong

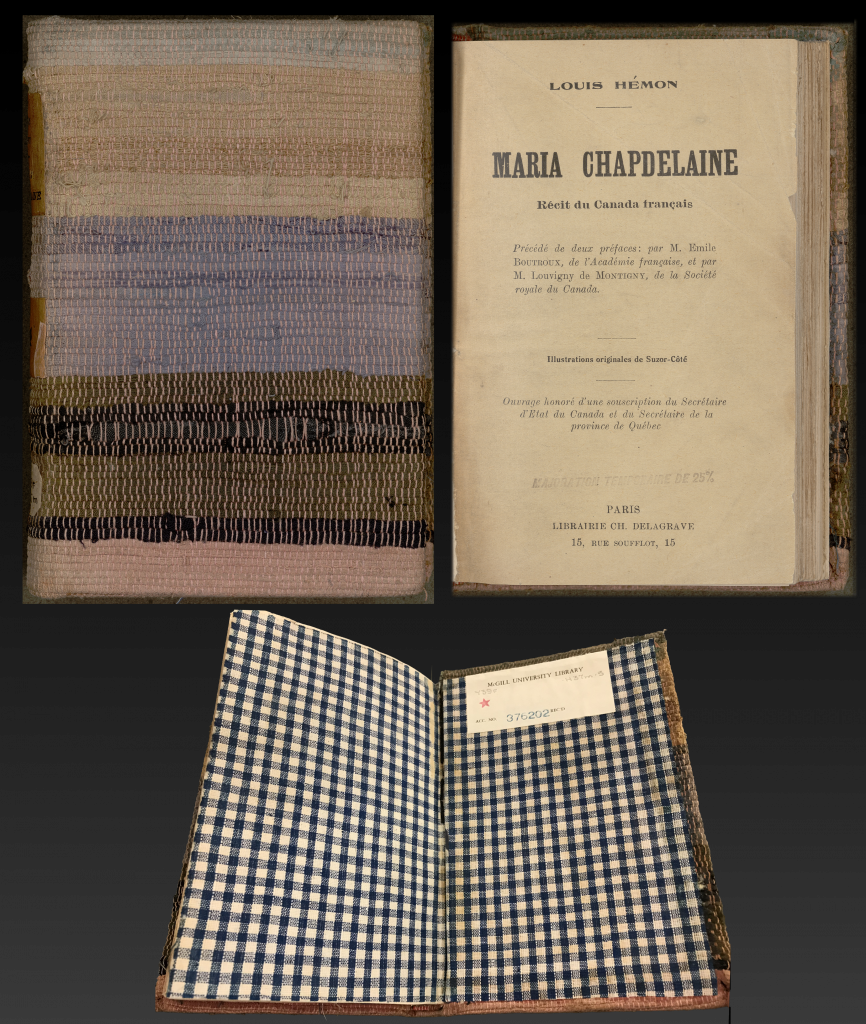

Louis Hémon (1880-1913).

Maria Chapdelaine: Récit du Canada Français.

Paris: Librairie Delagrave, 1916. Bound in original textile art.

This Barbie is Rare Books’ resident classics student, whose second love (books being the first, obviously) is textile art. I love crocheting, sewing, needlepointing, embroidery, cross-stitch — pretty much anything art that has thread in it. That’s why one of my favourite finds from Cutter is Maria Chapdelaine: Recit du Canada Français, a book that was handbound in fabric. The outside is a hodgepodge of fibers sewn directly onto the board. The endpapers are also fabric, a blue and white gingham reminiscent of a picnic blanket, or perhaps Dorthoy’s dress from The Wizard of Oz.

The stitching may be wildly uneven, and the thread may be falling out in some places, but the care that was put into the binding of this book is evident. In an era where everything is mass produced, it’s commendable to hold an object that was made by hand, with love. I only hope that the original artisan knows that their creation is in good hands, and that their creative legacy lives on.

Our thanks to all our dedicated students.

Quelques trésors que nous chérissons

Nous avons engagé une joyeuse bande d’étudiantes et d’étudiants de premier cycle le trimestre dernier pour éplucher systématiquement une portion des rayons des Livres rares et collections spécialisées afin de stabiliser les livres ayant le besoin le plus urgent d’être protégés. Leur tâche s’échelonnant sur plusieurs mois, ils ont eu l’occasion de se familiariser avec quelques impressions et reliures notoires. La plus grande part de leurs efforts a été dirigée sur la Collection Cutter, un assemblage de certaines de nos premières acquisitions de différentes dates et langues sur divers sujets. Cinq de ces étudiantes et étudiants ont été invités à choisir un ou deux livres et à expliquer pourquoi ceux-ci les interpellent particulièrement. J’ai partagé allègrement leur enthousiasme pour leur sélection puisque ces documents sont tous uniques en un sens. Il est aussi rapidement devenu évident que ce travail de stabilisation allait être aussi bénéfique pour les livres que pour ceux qui en retirent une expérience d’apprentissage sur l’histoire du livre. Ces joyaux témoignent de l’évolution et de la diversité des techniques de production et de reliure, et ils ne représentent qu’une petite portion des merveilles qui reposent dans nos rayons. Nous espérons que ces récits avisés et intimes sauront vous plaire. – Ann Marie Holland, rédactrice et superviseure des étudiants

Eden Autmezguine

Johannes Crotus Rubeanus (1480-1539).

Epistolae Obscurum Vivorum. (Lettres d’hommes obscurs).

Francoforti ad Moenum:1599. Couverture formée d’anciens manuscrits.

J’adore les histoires, et tout ce qui a une histoire à raconter, même si je ne saisis pas tout. Lorsque je travaille sur un livre, j’essaie souvent de m’imaginer par quelles mains il est passé avant de se rendre aux miennes, en particulier celles qui lui ont donné vie, et de découvrir des traces visibles de son passé. Parfois, ces indices rendent son histoire d’autant plus fascinante et énigmatique, comme c’est le cas avec ce livre. Écrit en latin, il a été publié en Allemagne en 1599. À l’intérieur, le texte est orné de lettrines et de culs-de-lampe xylographiés. De légères marques laissées par les attaches qui ont servi à le lier sont encore visibles sur les plats recto et verso. La reliure souple est composée de vélin avec rabats en gouttière, plus rigide qu’un livre broché moderne, mais plus flexible qu’un livre cartonné. Ce qui rend ce livre véritablement spécial cependant est le choix d’un manuscrit en hébreu pour sa couverture.

Au Moyen-Âge, puisque le vélin était à la fois précieux et durable, les feuillets qui avaient composé des livres étaient souvent réutilisés pour relier de nouveaux livres. En outre, les chrétiens utilisaient fréquemment des matériaux provenant de bibliothèques juives à ces fins. Ce fragment en couverture provient vraisemblablement d’un plus grand volume. La colonne de texte principale, avec de magnifiques caractères larges manuscrits, s’étend du milieu du plat recto jusqu’au milieu du plat verso. Il m’a été possible de l’associer à une portion du Qohélet (Ecclésiaste), plus précisément la fin du chapitre huit et le début du chapitre neuf. L’écriture ktav (traditionnelle) correspond aux Ashkénazes du 14e ou 15e siècle, possiblement en Allemagne, en raison des marques nikud (diacritiques) et te’amim (cantillation). On remarque aussi des notes massorétiques dans les marges supérieures et inférieures. La colonne de texte plus petit à droite sur le plat verso, dont on ne voit qu’une partie, correspond vraisemblablement à un commentaire. Un examen attentif permet aussi de détecter de légères marques d’impression de lettres laissées par le texte au revers.

Fait surprenant, il semble y avoir un lien entre le fragment ayant servi à la reliure et le contenu du livre! Ces Lettres d’hommes obscurs constituent un recueil de lettres satiriques en soutien à l’humaniste allemand Johann Reuchlin qui ridiculisent la scolastique et le monachisme, en grande partie en se faisant passer pour des lettres de théologiens chrétiens fanatiques discutant de la nécessité de brûler ou non tous les livres juifs. Et ce qui n’est pas sans intérêt est que ces lettres s’appuyaient sur de réelles querelles publiques entre Reuchlin et Johannes Pfefferkorn, un ancien juif converti au christianisme qui a tenté de faire détruire tous les exemplaires du Talmud. Ironique, donc, que ce volume en particulier ait été relié avec un fragment de livre juif, en hébreu d’autant plus. (Remerciements particuliers aux Prof. Deborah Abecassis et Jen Taylor Friedman pour leur aide et leur expertise.)

Jamie Farr

Henry Scholey Saunders (1864-1951).

Whitman Photographs.

Toronto: Henry S. Saunders, 1939. Avec photos collées. Exemplaire no 4 d’une édition limitée.

Présenté à la bibliothèque par Lady Amy Redpath Roddick.

J’ai rapidement découvert en travaillant dans l’aile des Livres rares et collections spécialisées que le vieux dicton est vrai : ne jugez pas un livre à sa couverture. Ici, la reliure est plutôt banale : beige et rigide, mais tout de même bien conservée pour un livre de 1939. Les pages sont en carton, ce qui n’est pas courant pour un livre de cette époque, et plus on y regarde de près, plus les excentricités se révèlent d’elles-mêmes. Ce livre de H.S. Saunders fait partie d’une collection en neuf volumes qui contiennent plus de 300 objets commémorant Walt Whitman dans sa façon de s’habiller, de se présenter et d’être tout au long de sa vie. Chaque livre a été entièrement fait à la main, puis numéroté et signé par Saunders lui-même. Dans celui-ci, on découvre des reproductions de portraits, de peintures, de dessins et de bustes du poète Walt Whitman. En le feuilletant, on peut voir par endroit des marques où les photos ont été collées sur les pages, alors que certaines sont un peu de travers. Saunders a griffonné des légendes sous chacune des 100 images, dressant un portrait de la vie de ce talentueux écrivain sous un angle inédit. Le dévouement de Saunders à archiver et à honorer la vie de Whitman est évident dans cette œuvre historique faite à la main, et la manipuler ainsi est une expérience grandement émouvante.

Il va sans dire que la prose de Whitman transcende les époques. Ces photos, quant à elles, sont bien ancrées dans les menus détails de sa vie. Les images 28 et 29 sont respectivement une photo et un dessin de Whitman et de son partenaire de longue date, Peter Doyle. Avec leurs chapeaux melon agencés, assis côte à côte, le bras de Doyle contre la jambe de Whitman. Alors que la poésie de Whitman regorge d’éléments qui explorent et mettent en valeur la figure masculine, le poète est lui-même décédé au tournant du 19e siècle, avant la montée des mouvements de libération queer. De son vivant, il a subi les pressions d’un ensemble de plus en plus strict de lois sur la « moralité », contrôlant sa relation avec Doyle et repoussant son histoire queer personnelle en marge du reste. Même l’œuvre de Saunders, assemblée plusieurs années après la mort de Whitman, n’a circulé qu’au sein d’un petit cercle d’amis de confiance. Loin des yeux, loin du cœur, les espaces queers fréquentés par Whitman avaient été réécrits et oubliés. L’histoire reprend cependant sa place dans le milieu universitaire moderne grâce au don de ce livre à la Collection Cutter par Lady Roddick, et Whitman peut dorénavant être pensé à la fois comme poète, personne queer et (le plus important sans doute) new-yorkais.

Maggie Nielsen

Chiang T’ing Hsi. Encyclopédie

chinoise active du 18e siècle. ca. 1716. 2 volumes. Avec xylographies; dans un boîtier à 4 rabats recouvert de brocart.

J’ai toujours eu un fort attrait pour l’esthétique, et je conçois qu’il s’agit de mon moyen le plus élémentaire pour faire l’expérience du monde autour de moi. Ce n’est donc pas surprenant que ce soit souvent l’aspect matériel d’une œuvre qui retienne mon attention parmi les Livres rares. J’ai d’abord entrevu la reliure en brocart de soie bleutée de cette encyclopédie chinoise du haut d’un rayon. Son boîtier s’ouvre d’une façon spectaculaire, avec ses rabats à motifs en spirale qui s’imbriquent, et révèle deux livres à couverture en papier parsemée d’or reliés par un fil doré. Une inscription à l’intérieur de la boîte indique qu’il s’agit de recueils sur le « royaume végétal », faisant partie d’une encyclopédie produite en 1716 sous l’ordre impérial chinois. En les feuilletant, on découvre des colonnes de caractères chinois soignés, possiblement imprimés à l’aide de caractères mobiles en cuivre. Ce que je préfère, cependant, ce sont les illustrations de la flore diversifiée. D’une manière fidèle à la tradition des paysages chinois, les lignes délicates de ces images imprimées tracent les courbes adoucies et les motifs d’écorce d’arbres variés, in situ, parmi quelques cailloux raboteux. Par sa matérialité, cet objet offre une brève leçon d’histoire culturelle, tant par ses techniques de reliure et ses matériaux délicats que par son désir de normaliser les connaissances à une époque de plus en plus modernisatrice.

Sir Walter Scott (1771-1832).

Poems of Sir Walter Scott. Edinburgh: W.P. Nimmo, 1861. Avec reliure en bois sur mesure.

Ce second livre, un recueil de poèmes de Sir Walter John, représente d’une façon très différente une matérialité tout aussi soignée. Les plats recto et verso du livre sont recouverts de bois vernis et ornés de clous nacrés aux quatre coins. Au centre sur le plat recto, une miniature délicate représente un château sur une falaise surplombant la mer. Une petite inscription au bas indique que la couverture est « faite de bois provenant de la salle Douglas du Château Stirling, récupéré après l’incendie du 18 novembre 1855 », ce qui porte à croire que cette reliure unique a une grande valeur sentimentale à titre de vestige d’une ancienne demeure.

En travaillant dans cette aile, j’ai appris à reconnaître la valeur des livres comme objets personnels : leurs propriétaires les collectionnent, les emportent, marquent leurs pages et y ajoutent des notes dans les marges. Et ce livre-ci en est un magnifique exemple. Ses annotations, tant dans les marges que sur les couvertures, nous offrent un regard privilégié sous forme de microrécits rédigés par ceux qui nous ont précédés.

Adrienne Roy

The Canadian Birthday Book. S. Frances Harrison (1859-1935), ed. Toronto: C. Blackett Robinson, 1887.

Présenté à la bibliothèque par W.D. Lighthall (1857-1954).

Je ne peux pas nier que je suis une véritable Lion. Même si je rejette l’opinion que nous sommes un stéréotype de vanité – je dirais plutôt que nous sommes simplement très passionnés – ce n’est pas spécialement étonnant que j’aie tout de suite remarqué The Great Canadian Birthday Book. Après quelques mois à travailler dans l’aile est des Livres rares, moi et les autres étudiants responsables de la stabilisation de la Collection Cutter avons commencé à nous sentir un peu las, mais cette petite trouvaille dans la dernière rangée m’amuse beaucoup depuis. Maintenant, dès que je tombe sur ce petit livre carré à la reliure vert foncé, je ne peux m’empêcher de l’ouvrir et de relire le poème de ma naissance, puis de demander à mes collègues quelle est leur date d’anniversaire afin que je puisse lire le leur également.

Publié par C. Blackett Robinson en 1887, The Great Canadian Birthday Book n’est pas une anthologie de la poésie canadienne puisque, comme l’indique sa préface, « l’espace nécessairement limité d’un livre de naissance lui interdit forcément ce titre ». En plus de présenter des vers en anglais et en français remontant jusqu’à 1793, ce coffre au trésor de la poésie canadienne cache un autre joyau pour ceux qui se donnent la peine de le lire avec le sérieux qu’il mérite : une délicate fleur séchée a été pressée entre les pages des 13 et 14 décembre, avec une petite note manuscrite : « Un bouton de rose pour la jeune dame ». Ayant terminé ma troisième année de majeure en anglais, je vous assure que mon penchant pour la littérature s’étend bien au-delà des livres sur les naissances. Cela dit, une des choses que je préfère à travailler ici dans les Livres rares, c’est de voir toutes les manières dont d’autres personnes ont aimé ces objets bien avant que je les découvre.

William Wordsworth (1770-1850).

The Poetical Works of William Wordsworth. London: George Routledge and Sons, 1833.

Illustrations en ajout, reliure soignée, signé par F. Maullen. Un don d’Alice Redpath.

Au-delà de côtoyer certaines œuvres des personnages les plus prolifiques du monde littéraire, une des choses les plus fascinantes de notre travail dans la division des Livres rares et collections spécialisées est de découvrir les manières dont les livres peuvent être magnifiquement reliés. Cet exemplaire de The Poetical Works of William Wordsworth correspond de façon spectaculaire à ces deux phénomènes. Orné de motifs floraux en relief et de feuille d’or, ce livre ferait un superbe présent comme le faisait remarquer une collègue. À savoir si celui-ci a été ou non offert en cadeau jadis reste un mystère, mais quoi qu’il en soit, le revers de la garde de soie nous révèle qu’il a appartenu à Alice Redpath, une importante donatrice pour les Bibliothèques de McGill. Ses contributions continuent de remplir et de décorer nos rayons, et nous en sommes vraiment reconnaissants.

Olivia Wong

Louis Hémon (1880-1913).

Maria Chapdelaine: Récit du Canada Français.

Paris: Librairie Delagrave, 1916. Relié avec une œuvre textile originale.

Représentante des études classiques dans les Livres rares, j’ai un grand amour que je ne cache pas (après mon amour pour les livres, bien entendu) pour les arts textiles. J’adore le crochet, la couture, la tapisserie, la broderie, le point de croix, bref pas mal tout ce qui relie l’art et les tissus. Voilà pourquoi cet exemplaire dans la Collection Cutter de Maria Chapdelaine: Recit du Canada Français, relié avec des pièces de tissu, est une de mes plus belles trouvailles. La couverture est composée d’un assortiment de fibres cousues directement sur le plat. Les gardes sont aussi en tissu : un guingan bleu et blanc qui rappelle une nappe de pique-nique, ou même la robe de Dorothée dans Le Magicien d’Oz.

Même si les coutures sont manifestement inégales et que les fils se défont par endroit, ce livre a été relié avec un soin bien évident. À une époque où tout est produit en série, il est louable de tenir un objet qui a été fait à la main, et avec amour. J’espère que son créateur sait que son œuvre est entre bonnes mains, et que son héritage créatif reste bien vivant.

Nos remerciements à nos étudiantes et étudiants dévoués.

Très bien écrit et informatif! Merci pour ces témoignages.

Philippe Bourque