by Jessica Huang, Student Project Assistant, Rare Books & Special Collections, 2025 (BSc Pharmacology, Philosophy minor)

“The more abstract, the more ideal an art is, the more it reveals to us the temper of its age. If we wish to understand a nation by means of its art, let us look at its architecture or its music.”

These are the words of Oscar Wilde in “The Decay of Lying”, from notes that I came across while looking through the John Bland Canadian Architecture Collection (CAC) at the McGill University Rare Books & Special Collections as I helped curate the architectural archives exhibition Everything but the Blueprint: What Archival Documentation Reveals about the Architect as Student, Educator, and Practitioner.

Sentiments like these on the philosophy of art were what made me so drawn to the architectural archives, from the very first day. Within the CAC room’s high ceilings and arched windows, I flipped open sketchbooks to architectural ornamental details in pen, and pulled open drawers to film slides of buildings from all over the world.

Coming from science and philosophy rather than architecture, I looked at everything with fresh eyes. I had led curation and creative direction in art publications before, but this was still unusual preparation for a role in architectural archives. I found myself looking at creative work analytically, seeing where art and science met. Indeed, architecture fulfilled both aspects: the engineering precision, and the humanist questions about what people need and how beauty serves function. Every building is applied philosophy and structural engineering, at once. While I started with minimal knowledge on architecture, I understood how to look at art, see connections, and think analytically about how scientific thinking shapes creative work. Within a few weeks, I was deeply immersed in architecture, a world for which I’d previously had only passing interest.

Every day I spent uncovering new, beautiful, hand drawn material in the CAC made me more entranced by the breadth and depth of both the collection, and the discipline of architecture in general.

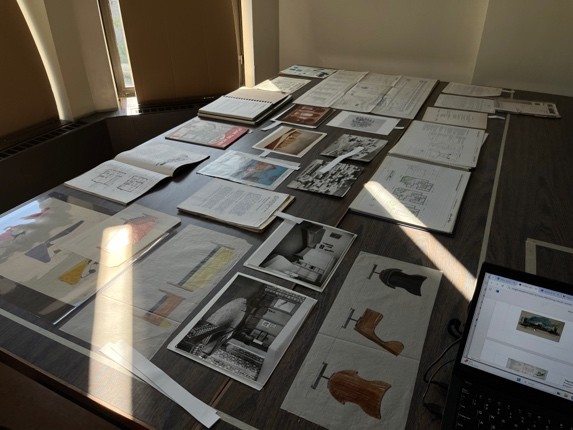

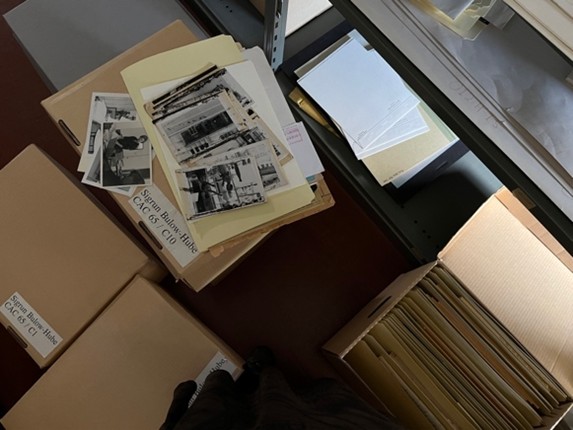

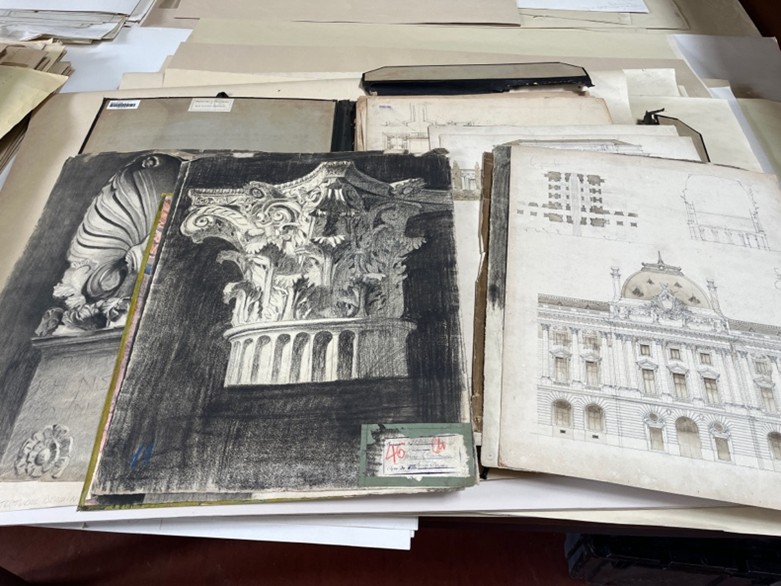

Throughout the summer, I progressed through many drawers, folders, and boxes, uncovering student sketchbooks, handwritten notes, typewritten notes, and large-scale sketches and drawings. There was one particularly stunning collection of big charcoal, graphite, and watercolour sketches of column and ornamental detail that had incredible contrast and detail. These weren’t technical blueprints, but artistic studies. It struck me that someone had spent hours rendering shadow and texture on a Corinthian capital, not because it was necessary for construction, but because understanding beauty required this kind of meticulous attention.

My favourite collection of text was teaching notes from Peter Collins for an architectural abstraction course, probably due to its relation to philosophy. Collins’ notes explored abstraction in architecture—the relationship between ideas and built form. It echoed the argument for architects to think abstractly before they can build concretely, and how every building begins as an idea about human needs, space, and beauty, before it becomes steel and concrete. These fundamental questions about what architecture is for felt very significant for me.

I found the tactile nature of my work particularly remarkable. In museum exhibitions, we as the public seldom get to touch the artworks. We rely primarily on sight, regarding the art and accompanying labels, keeping our distance. But looking through the architectural archival material, I was able to touch every page with my hands. This was a privilege I hadn’t preconceived would add so much to my experience of the art. Touching made it all the more tangible and palpable.

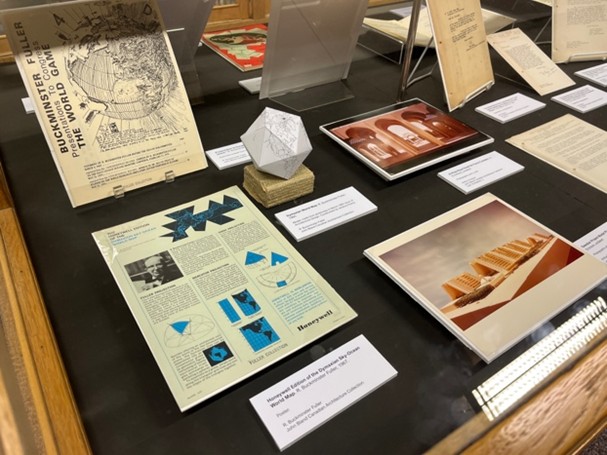

Tracing my finger over each hand drawn line and word instilled in me a sense that someone made this; someone etched every line. What became clear to me was the notion that, across time and space in human history, people have always wanted to create something beautiful. It was so personal, G.E. Wilson’s sketchbooks, Buckminster Fuller’s grand multidisciplinary ideas, Safdie’s sketches and margin notes, Bland’s notes on pedagogy as architecture school director. I was entranced.

The glass display cases of exhibitions separating the art from the viewer forms an emotional distance. This raised a curatorial question I thought about throughout: how do you convey sense of presence and closeness through the glass? How do you help viewers sense the hand that sketched the line when they can’t touch it themselves? It’s easy to overlook this, because viewers only see the art behind the glass, never experiencing it the way curators do. This was the case for me, and breaking this wall struck me in how I now perceive art and exhibitions in general.

While there was no alternative to glass display cases for our exhibition, I hoped that through the work I was doing, some of that tangibility would still translate for the viewer.

After a summer of reviewing countless folders of material, I began creating structural supports for the exhibited materials and constructing the paper geodesic dome in September. The day of installation came, and we carefully placed all the materials in the cases. It felt like months of work would finally be seen by the public.In the weeks following, I’ve brought friends to the exhibition. (I know a spot!) Sometimes, I catch visitors or wandering students leaning close to the cases, faces inches from the glass. Some point at notes, others photograph the sketches.

The exhibition is about the relationship between students, educators, and practitioners in architecture, and how knowledge moves between these roles. What emerged for me was also the realization that in architecture, beauty and function exist not in tension, but in co-existence.

My summer spent working on this exhibition was transformative. I came into this work having grown up reading, writing, and creating art and music, then pivoting to pursue science without wanting to fully leave art behind. The architectural archives let me fulfill a part of myself that I had set aside as secondary. What these materials revealed to me is that every building, sketch, and marginal note is evidence that people have always wanted to work out how to make something both beautiful and useful.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.