By Aurora Rose Desjarlais (Nêhiyawak/Plains Cree First Nations, McGill Visual Arts Collection Intern, 2025-)

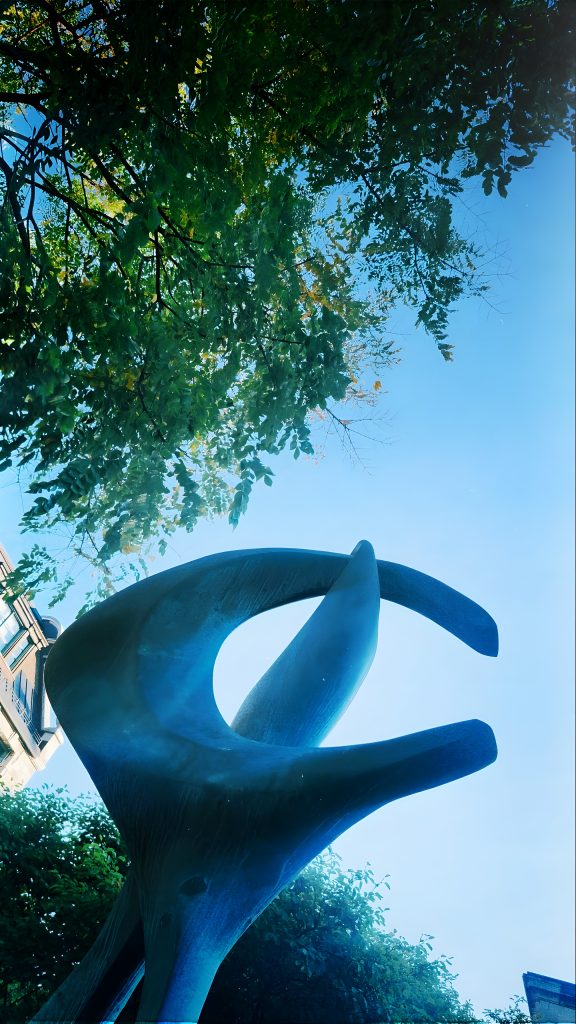

A sculpture that has always caught my eye on McGill’s campus is Exaltation by Giovanni Porretta. It is located in the James Sculpture Garden, which is nestled between the Milton Gates, James Administration Building, and McConnell Engineering Building. This busy campus crossroads is a key gathering place for the McGill community, and the open-air sculpture garden enhances the experience of the works as the seasons shift around them. As an Art History student, I pass through the garden often. Exaltation has witnessed the community across many seasons, and I have photographed it throughout the year (Figures 1–3). Its form evokes the Ionkhisotha Ahsonthennékha Karáhkwa/Nookomis Giizis/Tipiskâwi-pîsim/Moon, prompting reflection on Indigenous teachings, stories, and cultural practices that honor the Moon across Turtle Island.

Exaltation is made of bronze with a granite base and stands over 3 meters tall. It has a three-dimensional verticality and is not symmetrical along the vertical axis but flows around it in a delicate and smooth wavy pattern. The wavy form suggests an inherent motion, though it is eternally still in its bronze cast. The texture of Exaltation is smooth, due to the use of distinctive tooling by the sculptor.[1] The patina is emerald to forest green and varies throughout the work of art from light to dark shading, most likely affected by the outdoor location of the sculpture. It is open to the elements of the weather, air contents, humidity, rain, sunshine, and snow in the winter. This has contributed to the variance in green patina, creating distinctive colored lines throughout the surface. The green patina indicates an inherent environmental element that links the bronze sculpture to its crescent moon shape.

Figures 1-3: Giovanni Porretta, Exaltation, 1981, Bronze with Granite Base, Gift of Thomas O. Hecht, McGill Visual Arts Collection, 1996-021. Photographs taken and edited by Aurora Rose Desjarlais, Summer, Fall, Winter 2025.

As an abstract sculpture, it invites varied interpretations; viewers often see different meanings in the same work, shaped by their own perceptions. When I first saw this sculpture, I saw an elegant crescent moon that seemed to be in perpetual motion of being lifted into the heavens. Since it is held in place by the bronze and granite base, there is a perpetuity in the suggestion of motion, so it is eternally depicting the duality of motion and stasis that intertwine. This is a nod to the title of the artwork, Exaltation, which means “to raise in rank, power, or characters” and “to elevate by praise or in estimation.”[2] To rise in rank or power alludes to a transitory motion and action, which is in alignment with the duality of the sculpture. The sculpture seems to be visually in the process of rising, or even falling, depending on your perspective. The cycles of the moon vary, depending on the day, and its path around the Earth. There is a sense of the moon’s diversity in path in the sculpture. Even as you walk around it, it travels according to your path and direction. The moon, interconnected with Earth, follows paths that take it up or down, around, and in angles of all sorts around the planet. Sometimes you see the moon in its phase in the East, West, North or South, as it travels continually around us. The inherent static position of the sculpture and perpetual cycles of the seasons around it mirrors the relationship that we have with the moon and our daily observation of it. The inherent stasis of the sculpture also relates to the perpetuity of the moon, and how it has been connected to us for many revolutions around the sun, being observed by countless people over the centuries.

The Ionkhisotha Ahsonthennékha Karáhkwa/Nookomis Giizis/Tipiskâwi-pîsim/Moon has always been one my favorite “heavenly objects” to admire in our sky, as it is always going through a perpetual cycle of life, death, and rebirth from our point of view. Our earth is intricately interconnected and intertwined with the moon in so many ways. In another sense, the moon, from our perspective, seems to be perpetually rising high into the sky, and returning down past the horizon. This endless cycle has been the scenery in the ever-changing sky above us. To superimpose the definition of the title with the visual analysis of the sculpture: I see a crescent moon shape that is being exalted and raised higher up. The sculpture towers high, encouraging all admirers to look up into the sky to admire it in its entirety. Reflecting upon this, the moon has been a prominent figure through many cultures, traditions and communities throughout history, all around the world. Looking up at the moon is something that I am sure that we have all done at some point in our lives. The moon connects us all.

I am from a First Nations Nêhiyawak/Plains Cree community from Alberta/Saskatchewan area. I initially grew up in that area, but I am now living at Tiohtià:ke/Mooniyang/Montreal. I remember learning about the many stories from Indigenous communities across Turtle Island as I grew up. I always found the stories to be exciting, and they provoked a curiosity for knowledge within me. That curiosity for knowledge continued to this day and so I have decided to continue my study with these stories while in University from an art historical perspective, as I have the honour of working at the McGill Libraries’ Visual Arts Collection as a Curatorial Intern. I want to emphasize that my study of these stories come from the reality that I am not an elder or an expert in these stories. The intention behind my writing it so introduce others to these various Indigenous stories that I have learned from experts and elders, but to also influence others to learn by their own curiosity. I recommend seeking out stories from Indigenous knowledge keepers and elders, if you would like to learn more. Through the examination of Exaltation, I see an opportunity to learn about Indigenous teachings and stories of the moon, many of which remain central to Indigenous community knowledge and cultural practices across Turtle Island and to share with you some of the knowledge I have found, as I am not an expert.

The sculpture was created by Giovanni (John) Porretta, who received his Bachelor of Fine Arts degree from the University of Guelph, Ontario in 1975.[3] His work has been shown in numerous exhibitions all over the world, in locations like Montreal, Guelph, New York, and Italy.[4] In 2012, Porretta was elected to the Sculptors Society of Canada.[5] According to his artist statement, Porretta views sculpture as an “infinite circle,” an idea that aligns with my own interpretation of the piece.[6] The concept of an infinite circle can be connected to the cycles of the moon, which perpetually goes through the multiple phases of the moon: new moon, waxing moon, full moon, waning moon, all the way back to the new moon again. The moon is infinitely cycling through the phases. Further than that, this sculpture does not depict a new moon or a full moon but depicts a crescent moon. From that depiction, there is an intrinsic tension of motion, or perpetual slow revealing of the moon over an imaginary stretch of time. This alludes to the process of an infinite cycle, further provoking the thought of this being a crescent moon.

Throughout many Indigenous communities, traditions and cultures, especially on Turtle Island, the Ionkhisotha Ahsonthennékha Karáhkwa/Nookomis Giizis/Tipiskâwi-pîsim/Moon directs the “calendar” that the traditions follow, amass knowledge from and adhere to. The communities that look to the moon in their traditions include the Anishinaabeg, Kanienʼkéha, Haida, Nêhiyawak, and many others around Turtle Island, from the north to south, and east to west. This tells us just how connected through the Ionkhisotha Ahsonthennékha Karáhkwa/Nookomis Giizis/Tipiskâwi-pîsim/Moon we all are, as we have all witnessed it throughout time and space and bring it into our stories and histories that we tell each other.

A teaching by Grandmother Isabelle Measawige from the Anishinaabe Serpent River Nation in Ontario, is that the Creator made Mother Earth, and she was beautiful, and he loved her with all his heart.[7] Mother Earth was given instructions, governance, and the power to give birth.[8] The Creator did not want Mother Earth to be lonely, so he created another woman named Nookomis Giizis/Grandmother Moon, who hangs in the night sky.[9] The Creator told her that she has the duty and responsibility to regulate life and to maintain the order in those communities; so, the Creator gave Nookomis Giizis/Grandmother Moon governance.[10] Nookomis Giizis/Grandmother Moon was not just a celestial body, but is a sacred entity intertwined with Anishinaabe and other Indigenous cultural values and governance principles. The Moon’s teachings are also connected to 13 sacred laws that guide one through life. The 13 Grandmother Moon laws encompass concepts of reciprocity, grace, cooperation, generosity, self-awareness, communication, forgiveness, impeccability, discernment, nurturing, compassion, gratefulness, and collaboration.[11]

The Anishinaabemowin word for the moon is Nookomis Giizis/Grandmother Moon.[12] The moon was created in the beginning of time to guide the Anishinaabe, as Elder Eddie explains.[13] The Anishinaabe host ceremonies to honor Nookomis Giizis that respect humanity’s relationships and responsibilities to her.[14] Anishinaabe relationships and responsibilities are entangled in stories, teachings, songs, and ceremonies for Nookomis Giizis that start with Creation. Every Nookomis Giizis has a name for a distinct seasonal event or harvest that takes place during that moon.[15] Grandmother moon/Nookomis Giizis entails the understanding and acknowledgement that the moon is always connected to bodies of water, including the water within us.[16] Kim Anderson, Métis scholar, explained that many Indigenous cultures participate in giving thanks to Grandmother Moon through moon ceremonies.”[17]

In the Kanienkéha:ka Creation Story, adapted from a story by Ionataié:was, Kanienkéha:ka storyteller, this world was made up of just water and creatures of the water.[18] Above the world, there was a place called Karonhiá:ke/The Sky World.[19] There was a tree growing in the center of Karonhiá:ke, called the Tree of Life.[20] One day, a woman who was expecting a baby, wanted to drink tea made from the roots of the Tree of Life.[21] Her name was Atsi’tsaká:ion which means Mature Flower or Ancient Flower.[22] Her husband, Otáhe, Guardian of the Tree of Life, went to retrieve some roots for his wife, but the tree fell down, creating a hole in the ground.[23] Atsi’tsaká:ion went to look at what happened and fell through the hole and grabbed onto some seeds from the roots and around the Tree of Life.[24] A flock of birds looked up and saw her falling, so they decided to try to catch her on their backs.[25] They wanted to bring her back up to the hole, but she was too heavy for them to carry higher.[26] They lowered her down to the water below, and a giant turtle said that they could put her on his back.[27] Atsi’tsaká:ion thanked the creatures and said that she needed land to survive.[28] They attempted to retrieve some dirt, but only the muskrat was able to get some for her.[29] When it was brought to her, she was able to create the lands that now live on.[30] This is the reason why people refer to North America as Turtle Island.[31] When Atsi’tsaká:ion passed away, her head was thrown into the night sky and she became Iethihsótha Ahshonthénhkha Karáhkwa/Grandmother Moon.[32] There here is an intricate connection between the Great Turtle and the moon calendar of many Indigenous communities on Turtle Island. There is a reference to the Great Turtle of Turtle Island and Iethihsótha Ahshonthénhkha Karáhkwa/Grandmother Moon currently at the new Y-intersection, renamed Tsi Non:we Onkwatonhnhets, or “The place where our life force emerges from the earth,” created by artist Alanah Jewell and consulted by Phillip White-Cree.[33] The work of art is part of the Visual Arts Collection at McGill. This stonework is a reference to the creation story of Turtle Island by Atsi’tsaká:ion/Sky Woman and the Ohén:ton Karihwatéhkwen/Thanksgiving address.[34]

For many Indigenous communities on Turtle Island, the Lunar Calendar is specifically mapped on the back of a mihkinâhk/turtle[35]. Mihkinâhkwak/Turtles usually have 28 “scutes” or plates on the outer circle of their shell.[36] This corresponds to the number of days in a Lunar Moon Cycle. Mihkinâhkwak generally also have 13 “scutes” in the inner circle of their shell.[37] This corresponds to the number of Moons in our year, which is the time it takes the Earth to rotate around our central star, the Sun. The 13 moons all correspond to the distinct environmental events that are unique to each Indigenous community. The moon in October is called Bnaakwii Giizis/Falling Leaves Moon for the Anishinaabe, and the moon in November is called Baashkaakodin Giizis/Freezing Moon.[38] For the Nêhiyawak (Y-dialect), the tipiskâwi-pîsim for October is called the Pimihâwipîsim/Migrating Moon and for November, it is called Ihkopîwipîsim/Frost Moon.[39] [40] There are different names for the Ionkhisotha Ahsonthennékha Karáhkwa/Nookomis Giizis/Tipiskâwi-pîsim/Moon, as every area experiences different environmental events in each month and it depends on the geographical location. From the names of the different moons, one can gather knowledge. Knowing their names, one would understand that it is time to prepare for winter, or time to prepare for spring, or even time to harvest. There is an inherent connection between the names and the environmental events that occur in each geographical area that are unique to Indigenous communities. The first day of the Lunar Month corresponds to the New Moon. Throughout history, the people observed that the environmental events, water level, weather, plant cycles, animal cycles, and temperature seemed to follow the cycles of the the Ionkhisotha Ahsonthennékha Karáhkwa/Nookomis Giizis/Tipiskâwi-pîsim/Moon.[41] Melba Green, Pimachiowin Aki Guardian from the Bloodvein River First Nation, explains, “The stars are used for directions, the sun is used to tell time, and the moon is used to tell you which month you are in.”[42]

Exaltation reminds me of the Ionkhisotha Ahsonthennékha Karáhkwa/Nookomis Giizis/Tipiskâwi-pîsim/Moon and encourages me to study Indigenous teachings about her across all of Turtle Island. The eternality of the bronze statue reminds me of the constancy of the moon itself. The shape of the sculpture also reminds me of the transient nature of its shape, perpetually revealing and concealing itself as it travels around our earth. It has inspired me to research and write about it. For this post, I researched Anishinaabeg, Kanienkéha:ka, Métis, Nêhiyawak, and Rotinonshón:ni knowledge originating on Turtle Island. I introduced stories about the creation of the moon, the creation of Turtle Island, and Tsi Non:we Onkwatonhnhets. I hope that you are inspired as well after reading about Indigenous Turtle Island teachings of our Ionkhisotha Ahsonthennékha Karáhkwa/Nookomis Giizis/Tipiskâwi-pîsim/Moon as I have been.

GIVING THANKS

I would love to take a moment to give my thanks to all of those that were involved with the process of writing my blog post.

Thank you to Michelle Macleod for her honored guidance with the writing and revising of my blog post.

Thank you to Dr. Madelaine Longman for her advice on perfecting the grammar and structure of my writing.

Thank you to Professor Wahéhshon Shiann Whitebean for her cherished teaching that has informed and guided my writing of this blog post that is the most respectful and honorable to Indigenous knowledge and sharing.

Without the thoughtful direction of these incredible professionals, I would not be able to give this sharing of knowledge the honor and respect that it deserves.

Finally, I also want to thank you to all of those that have taken the time to read my work after it was published. I truly appreciate your time, and I hope that my work has inspired you in some way.

Territorial Acknowledgement

I would like to begin by acknowledging that McGill University is located on unceded Indigenous lands. The Kanien’kehá:ka Nation is recognized as the custodians of the lands and waters on which we gather today. Tiohtià:ke/Montréal is historically known as a gathering place for many First Nations. Today, it is home to a diverse population of Indigenous and other peoples. We respect the continued connections with the past, present and future in our ongoing relationships with Indigenous and other peoples within the Montreal community.[43] [44]

[1] Fondazione Palazzo Strozzi (Florence, Italy), J. Paul Getty Museum, and National Gallery of Art (U.S.). Power and Pathos : Bronze Sculpture of the Hellenistic World. Edited by Jens Daehner and Kenneth D. S. Lapatin. Los Angeles: The J. Paul Getty Museum, 2015.

[2] “Exalt,” Merriam-Webster, accessed on July 30th, 2025, https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/exalt.

[3] “Giovanni (John) Porretta,” Art Public Montreal, accessed on July 30th, 2025, https://artpublicmontreal.ca/en/artiste/poretta-giovanni-john/.

[4] “John Giovanni Porretta,” Sculptors Society of Canada, accessed on July 30th, 2025, https://www.sculptorssocietyofcanada.org/john-giovanni-porretta/.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Ibid.

[7] “Grandmother Moon is sacred and should be respected,” Indigenous Watchdog, accessed July 30th, 2025, https://www.indigenouswatchdog.org/update/grandmother-moon-is-sacred-and-should-be-respected/.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Ibid.

[11] “Grandmother Moon is sacred and should be respected,” Indigenous Watchdog, accessed July 30th, 2025, https://www.indigenouswatchdog.org/update/grandmother-moon-is-sacred-and-should-be-respected/.

[12] Chiblow, Susan, “Relationships and Responsibilities between Anishinaabek and Nokomis Giizis (Grandmother Moon) Inform N’bi (Water) Governance.” AlterNative: An International Journal of Indigenous Peoples 19, no. 2 (2023): 283–92. https://doi.org/10.1177/11771801231173114

[13] Ibid.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Ibid.

[16] Ibid.

[17] Ibid.

[18] Mohawk Language Custodian Association – Kontinonhstats, Kanienkéha:ka Creation Story (Ottawa: Government of Canada, Winter 2016), 2-18.

[19] Ibid.

[20] Ibid.

[21] Ibid.

[22] Ibid.

[23] Ibid.

[24] Ibid.

[25] Ibid.

[26] Ibid.

[27] Ibid.

[28] Ibid.

[29] Ibid.

[30] Ibid.

[31] Ibid.

[32] Ibid.

[33] Cable, “McGill unveils redeveloped space.”

[34] Cable, “McGill unveils redeveloped space.”

[35] mihkinâhk means Turtle in Nêhiyawak/Plains Cree. Mihkinâhkwak is the word for two or more turtles.

[36] “Indigenous Moon,” Government of Canada, accessed July 30th, 2025, https://www.asc-csa.gc.ca/eng/youth-educators/objective-moon/indigenous-moon.asp.

[37] Ibid.

[38] Durham College, “The Thirteen Moons Teaching Cycle.”

[39] Cree Literacy Network, “Cree Language Calendar 2022.” Category: Calendar. https://creeliteracy.org/2021/09/07/calendar-2022-solomon-ratt/

[40] The Y-dialect corresponds to the Plains Cree.

[41] Cree Literacy Network, “Cree Language Calendar 2022.” Category: Calendar. https://creeliteracy.org/2021/09/07/calendar-2022-solomon-ratt/

[42] “The Lunar Calendar, Explained,” Pimachiowin Aki, accessed July 30th, 2025, https://pimaki.ca/the-lunar-calendar-explained/.

[43] This Territorial Acknowledge was written by Wahéhshon Shiann Whitebean and Dr. Karl S. Hele, with significant contributions at the final stages from Dr. Louellyn White. It has been edited for McGill University.

[44] Concordia, “Territorial Acknowledgement”

Bibliography

Cable, Eve. “McGill unveils redeveloped space” The Eastern Door, October 23, 2025. https://easterndoor.com/article/mcgill-unveils-redeveloped-space

Chiblow, Susan. “Relationships and Responsibilities between Anishinaabek and Nokomis Giizis (Grandmother Moon) Inform N’bi (Water) Governance.” AlterNative: An International Journal of Indigenous Peoples 19, no. 2 (2023): 283–92. https://doi.org/10.1177/11771801231173114.

Concordia, “Territorial Acknowledgement,” Indigenous Directions. Effective November 18th, 2025. https://www.concordia.ca/indigenous/resources/territorial-acknowledgement.html

Cree Literacy Network, “Cree Language Calendar 2022.” Category: Calendar. https://creeliteracy.org/2021/09/07/calendar-2022-solomon-ratt/

Durham College, “The Thirteen Moons Teaching Cycle.” Information and Resources. Effective November 10th, 2025. https://durhamcollege.ca/info-for/indigenous-students/information-and-resources/13-moons

“exalt,” Merriam-Webster, accessed on July 30th, 2025, https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/exalt.

Fondazione Palazzo Strozzi (Florence, Italy), J. Paul Getty Museum, and National Gallery of Art (U.S.). Power and Pathos : Bronze Sculpture of the Hellenistic World. Edited by Jens Daehner and Kenneth D. S. Lapatin. Los Angeles: The J. Paul Getty Museum, 2015.

“Giovanni (John) Porretta,” Art Public Montreal, accessed on July 30th, 2025, https://artpublicmontreal.ca/en/artiste/poretta-giovanni-john/.

“Grandmother Moon is sacred and should be respected,” Indigenous Watchdog, accessed July 30th, 2025, https://www.indigenouswatchdog.org/update/grandmother-moon-is-sacred-and-should-be-respected/.

“Indigenous Moon,” Government of Canada, accessed July 30th, 2025, https://www.asc-csa.gc.ca/eng/youth-educators/objective-moon/indigenous-moon.asp.

“John Giovanni Porretta,” Sculptors Society of Canada, accessed on July 30th, 2025, https://www.sculptorssocietyofcanada.org/john-giovanni-porretta/.

Mohawk Language Custodian Association – Kontinonhstats. Kanienkéha:ka Creation Story. Ottawa: Government of Canada, Winter 2016. Accessed November 11th, 2025. https://www.kanehsatakevoices.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/CREATION_-as-told-by-KANIENKEHAKA-woman-storyteller-FINAL2-April-13.pdf

“The Lunar Calendar, Explained,” Pimachiowin Aki, accessed July 30th, 2025, https://pimaki.ca/the-lunar-calendar-explained/.

“Thomas Hecht,” Montreal Holocaust Museum, accessed on July 30th, 2025, https://museeholocauste.ca/en/survivors-stories/thomas-hecht/.

Yellowhorn, Eldon, and Kathy Lowinger. “Turtle Island : The Story of North America’s First People.” Toronto: Annick Press, 2017. https://www.deslibris.ca/ID/454249.