During the winter 2015 term, McGill Library & Archives welcomed several practicum students from the McGill School of Information Studies (SIS). The SIS website outlines the practicum experience as

a 3 credit academic elective course in which master’s-level students participate in field practice under the guidance of site supervisors. Students benefit from the opportunity to apply their theoretical knowledge base and learning in a real-world setting, while gaining experience and practicing professional skills. Site supervisors and their workplaces benefit from the energy, knowledge, and skills of an emerging information professional while providing students with a valuable mentorship experience in a real-world setting.

Library Matters took a practicum pause with these students to talk about their work at the McGill Library & Archives and how their experience may help to inform Library units as they move forward with related projects. This interview features Pamela Casey. Pamela’s practicum at Rare Books and Special Collections involved processing a collection of late 19th-century travel photographs, surveying best practices involved in photograph collection management and developing a next steps plan for the collections like this at McGill.

Library Matters (LM): Tell readers a little bit about your practicum.

Pamela Casey (PC): My practicum involved exploring a photography collection found at McGill’s Rare Books and Special Collections (RBSC). This collection is distributed across over 40 boxes, albums and portfolios. A handwritten inventory was done in 1991 but the collection didn’t seem to have been touched since. There were two parts to the practicum: the first part was to conduct a survey to understand the content of the collection; the second part was to research best practices and write a report with suggestions on how to process, store, and make accessible photographic collections like this.

I spent the first two months surveying the collection. Each box and album contained a great variety of photographs of different sizes and in different conditions, some with identifying information and most not. The photographs had been organised by country or city. I began to realise was that these had originally been albums that someone at some point had dismantled, and then presumably split up according to subject. The photographs are of sites, cities and landscape views from all over the world, and date from the 1860s to late 1890s, with some from the early 1900s. What we presumed was that these were travel albums – a likely scenario is that someone would travel to Greece or Egypt or India, and buy a nice album from a local photography studio to bring home.

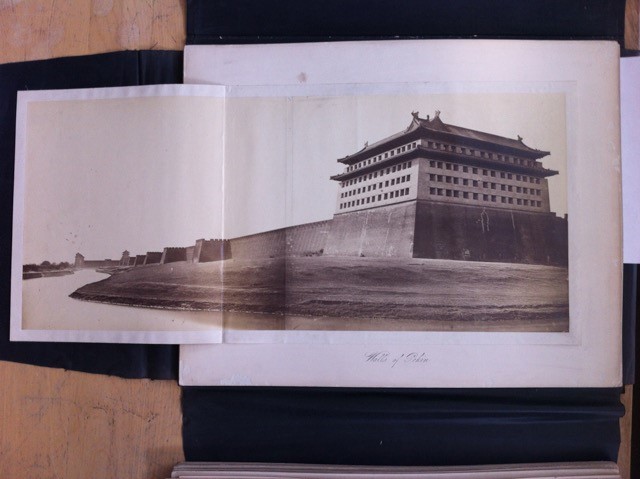

“Walls of Pekin”, from the China-India-Persia portfolio in a collection of 19th-century photographs. Rare Books and Special Collections, McGill University Library and Archives. Photo credit: Felice Beato

Sometimes there were donor markings which helped with research in RBSC’s accession files. Some photographs were donated to the library, and some were albums the library bought. There were a number of loose photographs, for example, that I’d found in a few different boxes which I realised were all part of a two-volume album the library had purchased from a studio in London, an amazing album of Greek temple ruins in Sicily and Greece. I did research into many of the photographer names that appeared, and started realising that many of them were quite well known.

This peaked everyone’s interest. It would seem that these photographs were initially valued for the places they represented, rather than their photographers – which also probably explains why the images were separated and classified according to country. I found that many of the photographers in this collection have had exhibitions dedicated to their work and had books written about them. This made it fairly easy to find material on many of them.

During the second part of the practicum, I did research into how similar collections of photographs have been managed elsewhere. For example, Harvard has a similar photography collection, though on a much larger scale, and has published a lot of materials on how to process and preserve them. We also ended up doing outreach and meeting with photography curators of cultural/heritage institutions in Montreal with similar collections. Many of the photographers featured in the RBSC collection are also included in collections at the CCA (Canadian Centre for Architecture). The McCord Museum has the Notman Collection which is of the same time period. The McGill University Archives also have a large collection of late 19th century and early 20th century photographs. My supervisor Jennifer Garland and I went to meet the people who handle these collections to see and ask questions about their storage facilities, what kind of enclosures they use, what type of access they allow, etc. Now that the best practices report is done, RBSC can hopefully use this to plan the processing of the entire collection at some point.

LM: Are there items in the collection that are unique to McGill?

PC: It’s unlikely, as these are photographic prints after all and we don’t have any negatives. But some of these are very special. For example, the “Cambodia” portfolio contains photographs of the amazing temple complex, Angkor Wat. These were taken by John Thomson, a Scotsman who was the first to ever photograph the site in 1865. These photographs bear the stamp of his studio in London so while they are not unique, they are still among the first photographs taken of the site.

I don’t have a background in photography history, but one thing I have taken from this whole experience is that it’s important to know as much as you can about a collection in order to make it interesting to future researchers. You have to have do some digging to get that kind of information and also share your enthusiasm with people. In my previous work as a researcher, the best experiences were when the archivist was deeply familiar with the material and helped make connections with other collection elements you might not have thought about.

LM: What did you take away from this project?

“Opening Box 11” from a collection of 19th-century photographs. Rare Books and Special Collections, McGill University Library and Archives. Photo credit: Pamela Casey

PC: I think it’s important to understand the personal value of the material, which is sadly something that’s been lost here because the albums were taken apart. The original albums might have had inscriptions or notes to give some clue as to where the photographs were from and how they got here. Being able to understand the custodial history of something is also an important part of authenticating it. The fact that the albums were separated shows that at some point in time, the value and information of the object was seen very differently than today. So I don’t know if this is a takeaway but I was really struck by this difference, and it made me curious to explore this idea in the context of library history.

LM: What do you wish you would have known before beginning the practicum?

PC: Because I had never worked with photographs before, I found that it took me a long time to gather information and understand about best practices. I probably should have done a little research into this before starting the practicum. That would be something I would recommend to others – once you discover what practicum you will be holding, figure out if there is anything that can give you some grounding beforehand. Now at the end of it all, looking back, I probably would have done the survey differently, such as tried to conduct a more thorough item-by-item inventory, and offered more protection to the photographs as I went.

LM: Do you get the sense that RBSC may continue to work on this project?

PC: I do hope so, and my impression is that it’s mostly a matter of getting the support to do it. I think processing and rehousing this collection would be an excellent practicum shared between two students, as it’s quite large and so likely too much for one person to do in four months.

LM: What brought you to McGill? What other types of work have you done?

PC: This is something of a second career for me. I worked in film in London for many years as a producer for the BBC, in commercials, and on independent projects, but it was difficult to sustain. I also worked as an editorial assistant and researcher for an architect friend and had the chance to visit a number of archives as part of this work. In 2010, I went to Columbia University where I did an MFA in writing. While I was there, I applied to their archival internship program and that was it for me. I really enjoyed the work and found that I was good at it. I enjoy the challenge of coming across a new collection, having no idea what each box contains, and having to piece together the story and figure out what’s important for other people to know about it.

LM: What brought you to Montreal?

PC: I’m from here originally, so I’m back home. When I started looking into MLIS programs, I was looking into programs around New York, where I lived at the time, as well as in the UK and in Canada. When I realised there was one at McGill, it just seemed right.

LM: What’s next for you? Do you plan to stay in the academic world?

PC: I would love to stay in Montreal and continue to look for work here. I would also like to stay in the academic world but I’m not tied to it. My goal is to work in archives or special collections, but I’m open to what comes next.

LM: You were given some great opportunities to take your work a little further through the Underwood & Underwood exhibit.

PC: Yes, the Underwood & Underwood collection is a slightly smaller photography collection within RBSC. A selection of these photos were recently included in Montreal’s Museum of Fine Arts exhibition “From Van Gogh to Kandinsky: Impressionism to Expressionism, 1900-1914”. When these photo were sent back to RBSC, I was asked to create a small exhibition with a selection of photos. I had never put together an exhibition before so I thoroughly enjoyed this experience, and also loved writing about it for the RBSC blog.

LM: Did you ever feel like Indiana Jones, going through all these little treasures?

PC: In a manner of speaking – they are so poignant. Given the events of the last few months with ISIS destroying towns and historical sites that have been around for thousands of years, these photographs also show places that don’t exist anymore. We have photographs of the Acropolis in 1878 when Athens was a sleepy agricultural town with sheep roaming the hills. It is something that is almost impossible to conjure up given the urban Athens of today. It gives a little thrill when you encounter the past in that unexpected way.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.