In 1973 the Van Horne Mansion, a historic brownstone located on the corner of Sherbrooke and Stanley Streets here in Montreal, was controversially dozed. This event came on the heels of a spate of similar demolitions in the Golden Square Mile. It occurred amidst organized protests and despite a notable public outcry, and it is credited with directly prompting the architect Michael Fish to found the community organization Save Montreal later that same year. It is also the background against which one young McGill undergraduate, Charles Gurd, decided to take his Leica M4 and document a number of the remaining residences in the district –presumably before these, too, could be gone.

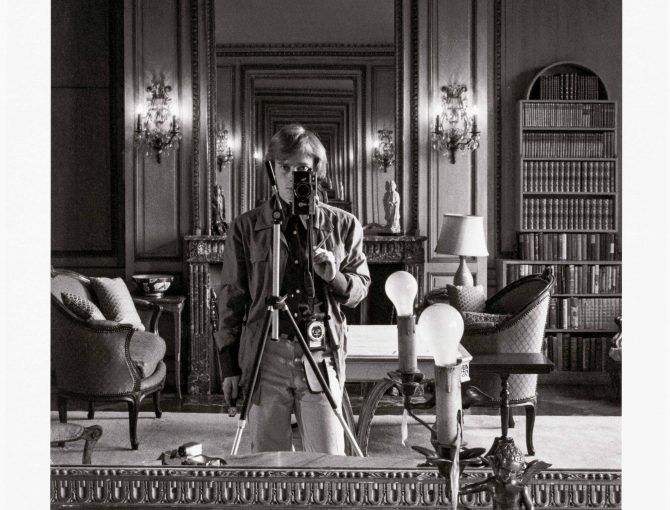

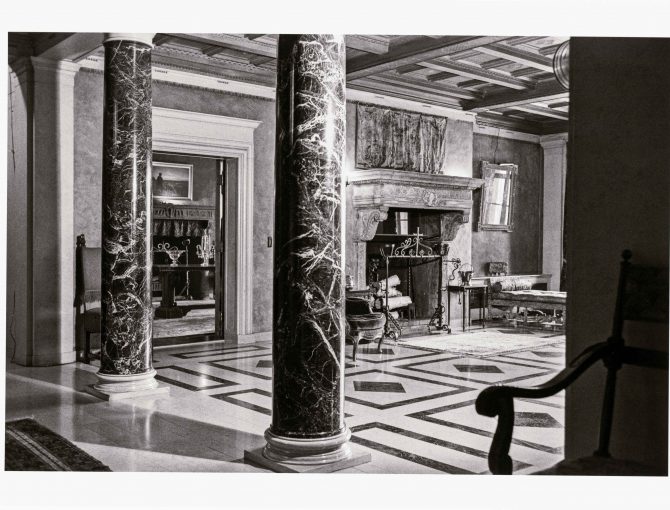

The result of that effort is a series of photographs called Montreal Mansions, which the Visual Arts Collection happily counts among its recent acquisitions. This work has gained new life through its exhibition at the McCord Museum, but Gurd originally completed it in 1974, while wrapping up his B.A. in Psychology at McGill, and just before beginning another degree in Architecture at Rice University in Houston, Texas. As part of his work on the series, Gurd had to gain entry to prestigious estates like the “McConnell House” at 1475 Pine West (also known as the “Jeffrey Hale Burland” House, Figs. 1-3) and the “Herbert Yuile House” at 3655 Redpath. He also traveled outside the city, where, near places like the Parc-Nature du Bois-de-Saraguay, Montreal’s wealthy elite once had their country homes.

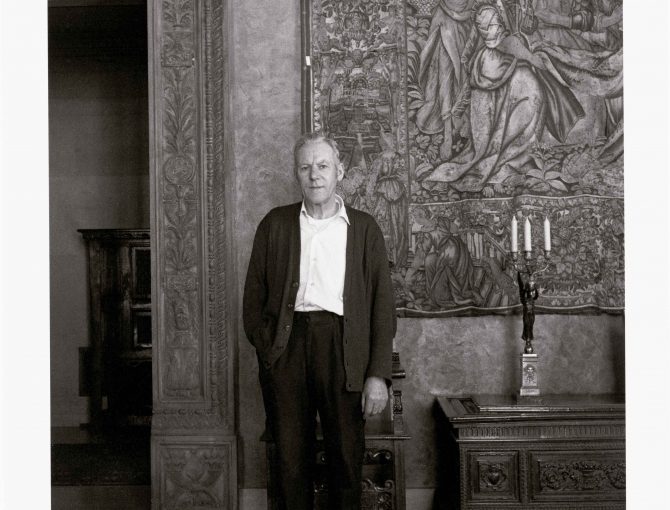

Gurd did not only take an interest in the status of these properties as endangered architectural monuments. His project was, beyond that, to document a dying way of life. Once on the grounds, his camera captured impressive lots and stately façades, but it focused on the opulent interiors: the interior tennis courts, the grand staircases, the fine art and furnishings populating cavernous sitting rooms. In the process, it also recorded family photographs, incongruous artifacts and décor that had clearly been acquired over time, and in rare cases, even staff (Fig. 2). This is why these photographs make for so poignant a record of Montreal’s architectural heritage. Collectively, they serve as a portrait, not just of a bygone culture and lifestyle, but of the individuals who once occupied these homes and of the lives these homes themselves once led.

At the time of their completion, Gurd simply set his negatives aside. He spent the next several decades focusing on his successful career as an architect, other art projects, and community engagement. But Gurd is also a talented photographer. These images are rich in detail, depth, and tone, and they are some of his best work. About 40 years after they were originally taken, Gurd removed the negatives from storage so they could be digitized and printed. In 2016, 40 of them were put on display in the exhibit at the McCord Museum. And now, he has donated one of three complete sets to the Visual Arts Collection, where they can be consulted by anyone with an interest in learning more about Montreal’s social and architectural histories.

A lot has happened between the time that Gurd created these photographs and the present-day context in which they have been presented to the public. Many of the residences have been named heritage sites. Some were transformed into apartments and office spaces, and one became a Benedectine priory before being returned, so it seems, to residential use in the 21st century. Still others survive here on the McGill campus as part of our cadre of “McGill Mansions.” The discrepancy between the contexts of Montreal Mansions’ production and reception highlights the way that discourses about decline, preservation, and heritage exist alongside the complicated processes of recycling and reusing our buildings. It also teaches us an important lesson about what there is to be gained by looking more closely at buildings, cities, and artworks as objects that exist in space, yes, but also in time.

-Written by Frances Cullen, Max Stern Fellow at the Visual Arts Collection

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.