By Chelsea Thompson Quartz, SIS Practicum Student, Book Arts Lab (RBSC). This blog post is complemented by a physical exhibition in the Rare Books & Special Collections reading room, April – September 2025.

Fleury Mesplet

Montreal formally enters the history of print in 1776, with the establishment of the not-yet-a-city’s first commercial printing press by Fleury Mesplet (1734-1794). Born in France, Mesplet came to Montreal from Philadelphia, after receiving funding from private donors (mostly his friend Charles Berger) and from the Continental Congress. The aim was to establish a French-language press in Canada, in order to bolster support for the revolution. Travel in the 18th century was perilous, however, and Mesplet lost a large portion of his (expensive) imported paper and printing supplies during a river crossing en route. Perhaps more perilously, by the time Mesplet arrived in Montreal in May of 1776, the tides of the revolution were already turning — American troops soon left Montreal, leading to Mesplet’s and his employees’ arrest and imprisonment at the hands of forces loyal to the British crown.

This imprisonment was brief, and upon his release, Mesplet set up shop on Rue Capitale, in the area that is now referred to as the Old Port. His shop was typical of such shops at the time, serving as both his home and place of business — with both printing press and bookshop operating on the site. In setting up in this way, Mesplet embodied the professional model that many would follow for the next century — that of the printer-publisher-bookseller, wearing many hats out of commercial necessity.

While Mesplet published a variety of religious and commercial pamphlets, booklets and other printed works — including his Réglement de la Confrerie de l’adoration perpétuelle du S. Sacrement, et de la bonne mort : erigée dans l’eglise paroissiale de Ville-Marie, en l’Isle de Montréal en Canada (second print edition), the first book commercially printed in Montreal (call numbers Lande 00153, Rare Books Main Collection BX816 C3 C56 1776b) — his most enduring legacy is perhaps his newspaper (the second run, which we will come to a bit later).

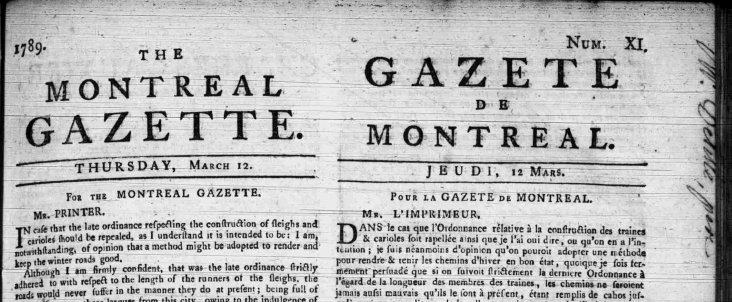

La Gazette [du commerce et] littéraire, pour la ville et district de Montréal was a French- language newspaper — the first in Canada —that ran for a year, starting in June of 1778. La Gazette was published as a four-paged quarto, with a subscription price of 2.50$ per year, with contents that included commercial news, literary commentary, advertisements, and essays.

Unfortunately, his prior imprisonment had led to additional scrutiny of what he published, and he had expressly assured authorities that he would not publish anything critical of the reigning religious or political authorities. His editor, Valentin Jautard (1738-1787), paid little mind to these assurances. A year less a day from the initial publication of La Gazette, on June 2nd, 1779, both Jautard and Mesplet were arrested and imprisoned. Their imprisonment lasted, unofficially, until 1782, at which time they were let out of prison without formal pardon.

While the imprisonment initially stalled the momentum of Mesplet’s printing enterprise, it does provide print historians a valuable insight into the kind of equipment he had been working with as Montreal’s first commercial printer — two presses and a supply of type, whose inventory was taken as it was seized upon his arrest. This same equipment was then leased back to him upon his release, allowing him to return to his work soon after.

Despite the outcome of his previous attempt at newspaper publishing, on August 28th, 1785, Mesplet published the first edition of the Montreal Gazette/La Gazette de Montréal, a publication that endures to this day. Unlike its original iteration, Mesplet’s second run was more typical of late 18th and early 19th century Quebecois periodicals, with split English/French- language columns. It was also a four-page quarto, and was published weekly at an annual subscription cost of 3.00$. A nearly 17% price increase after 6 years out of print may seem like a lot, but the imprisonment was a substantial setback, and Fleury Mesplet was running on a considerable deficit for basically his entire run as a printer.

When Mesplet died in 1794, after what was nonetheless a truly prolific career — he had the most individual imprints to his name of any individual Montreal printer of the era — his widow unfortunately inherited very little, if anything. His estate, including the furnishings from the home that adjoined his shop, was liquidated in order to repay his numerous creditors.

Among those who purchased from Mesplet’s estate was Edward Edwards (1756-1816), another printer-publisher-bookseller who had been sent to Montreal as an agent for Quebec printer William Brown (1737-1789), and who had also been tasked with keeping an eye on what Mesplet was printing. He acquired three printing presses and a supply of type in the estate auction, with which he intended to continue printing the Montreal Gazette as Mesplet’s successor, starting in 1795. There was a bit of a dispute over who would continue this legacy, however, as another version of the Gazette by another printer, Louis Roy (1771-1799), was run simultaneously for over a year, until Roy ran out of funding in 1797 and ceased publication.

Early 19th Century

This instance of competition between printers does reflect the evolution of the commercial printing environment in Montreal at the time — while Mesplet was the first commercial printer in Montreal, by the time he had passed he was far from the only one, and the print industry was growing nearly as quickly as the city itself.

Despite Edwards’ victory over Roy, his health soon failed him and he was forced to hand ownership of the Montreal Gazette to brothers Charles and James Brown in 1808. The brothers were already successful in publishing their own Canadian Gazette/Gazette canadienne starting in 1807, and James Brown (1776-1845) in particular is notable as a bookbinder, bookseller and businessman in the pulp and paper industry.

At this time, between the years 1810 and 1820, Montreal was experiencing its first boom in the print industry, with a major uptick in the number of both printers and materials being printed. As the city’s commercial prospects evolved and grew, the tendency of printers to also serve as their own publishers, editors and booksellers, among other things, began to dwindle. These professions would gradually become viable in their own right, though many printer-publishers persisted and even voluntarily supplemented their income by selling paper goods and serving as postmasters.

As of 1810, there were nine periodicals in circulation, a marked increase from only one in 1778. The success of these periodicals and their subscription model allowed printers to take on other projects, in addition to their usual commercial and religious commissions.

Within the province of Quebec/Lower Canada in this period, Montreal’s output was considerable — going from 23% of titles printed in the province between 1764 and 1810, to a whopping 55% of titles in 1815. For more statistics that a certain kind of person may enjoy: 21% of printed titles were religious texts, 16% were calendars, 6% were scholarly texts, and 4% were almanacs.

While concrete readership demographics of this period are hard to ascertain, there are other metrics which help paint a picture. The first Montreal library opened in 1796 with a total of 1558 volumes, of which 53% were in English. Many bookstores (“libraires”) of the era also doubled as stores for paper goods, general goods, and luxury imports, and many of these merchants had come from England — which reinforced the import of English goods and imprints. English-language literacy is also evident from the string of circulating libraries which were opened in the early 19th century, including the William Manson Circulating Library (1806), J. Laughlin Circulating Library (1818-1819), and McDonell Circulating Library and Reading Room (1819).

Despite the predominance of anglophones in the printing, bookselling and library spaces in this era, francophones were certainly not excluded from print and literacy’s march forward in Montreal. Joseph-Ludger Duvernay (1799-1852), for instance — who came up with the idea for St-Jean-Baptiste as a national holiday for Quebec — was a politician, printer and newspaper publisher whose print shop outputs represent a quarter of all titles published in Montreal between 1827 and 1837.

Mid-19th Century

Towards the midpoint of the 19th century, print in Montreal experienced another surge in popularity, spurred on by a number of cultural and social trends as well as some very specific measures undertaken by individuals in positions of power who had a vested interest in promoting Montreal print and literacy.

In Montreal, approximately 40% of the population was literate in 1840 — by 1870, literacy had expanded to the majority of the population. Duvernay, as mentioned above, was not just a printer but also a politician, who (echoing sentiments in Europe at the time) supported the advancement of the novel as a vehicle for moral guidance. This was a step towards novels being viewed increasingly as publicly acceptable to read, and therefore commercially viable to print and publish.

With novels entering the scene, circulating libraries opening up left and right (with real “public libraries” opening as of the 1880s), and an increasingly literate population, demands for printed materials by the average Canadian consumer climbed ever higher. Where there is a consumer market, however, there will be concerns about affordability. While Montreal’s print scene was growing rapidly, it was still supplemented substantially by imports from Europe and European copyrighted materials reprinted in the US. In an effort to curb this dependence and to encourage the consumption of local publications, a tax was established in August of 1850 on imported and reprinted materials that fell under British copyright.

As Montreal, Quebec, and Canada at large began to take shape culturally distinct and having their own identity in the 1850s, novels were just one vehicle for a new genre of work — “Canadiana”, which explored colonial customs and values, as well as themes that reflected life in Canada in this era.

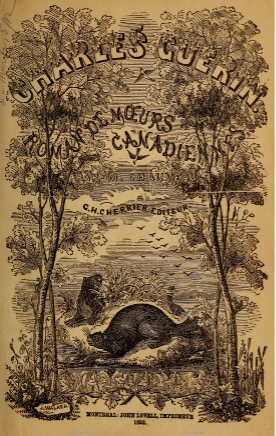

One example of a novel in this category is Charles Guérin : roman de moeurs canadiennes (Lande Canadiana Collection 01664) by Pierre-Joseph-Olivier Chauveau (1820-1890). This work, it could be said, represents a sort of microcosm of print and publishing culture in Montreal/Quebec at the time. The novel explores the life of a fictionalized young man of the time, and contains an overtly moralizing element alongside its depictions of life in Canada.

While originally printed in pamphlet form, the later edition held at McGill is a bound volume, has impressive printed front matter, and was printed by notable Montreal printer John Lovell (1810-1893). Additionally, the work contains an “avis de l’editeur” by G. H. Cherrier, in which Cherrier provides a window into sentiments towards printing and publishing at the time, including the struggle to publish works of a distinct Canadian/Quebecois character, as well as the burgeoning status and rights of the author as an agent in the printing/publishing lifecycle. For reference, writers in Canada only gained legal recognition of the intellectual and financial rights to their work in 1832, so when this novel and its “avis” were printed in 1853, it was still a newer development.

Chauveau was notably a politician in addition to his role as an author, and actually served as first premier of Quebec, though before this he succeeded Jean-Baptiste Meilleur (1796-1878) as superintendent of education for Lower Canada. Meilleur and Chauveau both established, in their tenure in this role, policies which encouraged the growth of academia in the province, and passed laws favouring literacy, libraries, and political scholarship — all of which contributed to the growth of printing in the 1850s.

Fun fact: if you grew up in Quebec and received a book as a prize for doing well academically, you have Chauveau and his “prize books” initiative through the Department of Public Instruction to thank.

Late 19th and Early 20th Century

Printing and publishing continued to be a major industry in Montreal in the late 19th century, with a boom in novels and catalogues in the 1870s and 1880s, and a surge of public libraries opening shortly after. The nature of printing, however, changed towards the end of the 19th century, as we saw the introduction of the linotype and monotype printing machines. Technology advanced quickly from there, and as of 1945 colour presses entered the scene, while the 1950s saw a shift towards offset printing.

This isn’t to say that the more traditional printing preferred by many lovers of book history had gone away entirely, but that shifts in industrial processes and technology had left letterpress and hand printing in the hands of aficionados, artisans and private presses.

On the artisan side, the 1950s saw the establishment of the Quebec school of engraving, leading to the publication of a new genre of livres d’artiste (artist books) and a growing movement towards cohesion within a series’ visual identity. Expo 67 subsequently allowed Quebec and Montreal to shine in their own right as possessing an internationally distinct graphic art movement.

This tendency towards devoted artisanship in the book arts was far from new, of course, with the Canadian small and private press movements having roots in the British Arts and Crafts movement, and specifically the work of William Morris. The emergence of the publisher-typographer in the Montreal/Canadian book arts scene (like Robert R. Reid, discussed below) was a hallmark of this period.

Montreal, as a bilingual hub of commerce and culture, was also a major hub for small press printing in both English and French up until the 1960s. Montreal was actually a hub for books in general, too, with multiple dedicated book fairs starting in this period. Some, like the Salon du livre du Quebec, started in 1959, are still running today. There were downsides to this concentration of book publishing and print-related commerce, however, and by the end of the 1960s many American and international companies, like McGraw-Hill and Prentice Hall, had established branch offices in Montreal. This inundation eventually led to the Act Respecting the Development of Quebec Firms in the Book Industry (RSQ, c. D-8.1), enacted in 1979, to bolster and protect local Quebec publishing firms. To this day, there are many measures enshrined in law and official policy that serve to protect the integrity of Quebec’s publishing industry.

Print at McGill Libraries

The William Colgate History of Printing Collection was established in 1956 thanks to a donation from William G. Colgate (1882-1971), facilitated by University Librarian Richard Pennington (1904-2003). This collection, along with the Lande Canadiana collection, are housed in the Rare Books & Special Collections department of McGill Library, and are a must-see for lovers of print and book history in Canada.

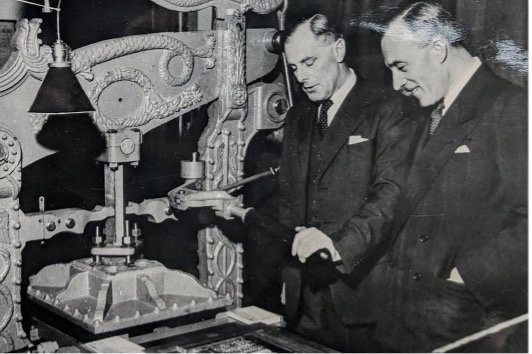

Among the collection’s holdings are a series of historical hand-presses and their various accoutrements— a Stanhope press, a compact Albion, and a large Washington press, as well as the visually striking Columbian press (originally established as pre-1824 and now established as having been produced in 1821). The Columbian in particular has a story behind it, having been found in an abandoned basement in post-war England in 1957 by Richard Pennington, while on a trip abroad funded by McGill.

The Columbian was functional throughout Pennington’s tenure as University Librarian, and its use at McGill and integration in the Library School curriculum coincides with the years of operation of the “Redpath Press,” from 1957 until Pennington’s retirement in 1965. The Redpath Press was the name Pennington gave his small press initiative, and much of its output is housed in McGill’s Rare Books & Special Collections.

While the Redpath Press formally ended upon his retirement, neither Pennington’s passion for hand-press printing, nor printing’s place at McGill, ended in 1965. The equipment and presses were passed on to Pennington’s successor, Robert R. Reid (1927-2022), who would go on to become one of Canada’s foremost typographers and book designers. His time at McGill would form a foundation for this lifelong passion, and upon his passing in 2022, McGill became home to a repository of a large portion of Reid’s work. Within McGill’s collections are numerous pieces of correspondence, and printed ephemera for both personal and professional projects — even the least of which shows evidence of Reid’s keen eye for design and composition.

One cannot talk about Robert Reid’s time in Montreal and at McGill (from 1963 to 1976) without acknowledging his monumental accomplishment — the Lawrence Lande Collection of Canadiana (1965), which is considered by many to be one of the most beautiful books ever produced in Canada, and a volume of which is often available for consultation in the Rare Book Reading Room. It was a substantial undertaking with an incredible result, and in light of contemporary print standards and technology, it can be easy to ignore how much work and thought would have gone into the volume’s creation and production.

Print at McGill Libraries Today

Print culture is kept alive at McGill today by a small but dedicated number of library staff, and more recently by practicum students and apprentices from within the McGill School of Information Studies. The Columbian press remains one of the stars of the show, with massive restorations undertaken in 2019, thanks to the Howard Iron Works Printing Museum and Restoration in Oakville, Ontario —the first time it had been restored since a friend of Richard Pennington (Charles Fisher) did work on the press in 1973-74.

The Columbian press is now housed in the McGill Book Arts Lab, formally inaugurated in 2020 within the Rare Books Reading Room on the fourth floor of the McLennan Library building, and is used primarily for print demonstrations in order to prevent undue wear and tear. It does cut an impressive figure in the window, however, where its iconic gold-toned eagle and elegant silhouette are visible from the library’s stairwell.

Future projects could, hopefully, bring the Stanhope and Washington presses back into working condition — for now, they rest in the library basement. Printing projects are undertaken on the Book Arts Lab’s other presses — a Farley proofing press, primarily used for student projects and cards, as well as the Pearl-brand clamshell press (which is a bit trickier to operate). For a number of occasions, hand-printed cards are available for purchase in the Rare Books Reading Room.

Further Reading

Gerson, C., Michon, J. (ed.) (2007). History of the book in Canada (v. 3. 1918-1980). University of Toronto Press.

Hamelin, J., Poulin, P., (2003). CHAUVEAU, PIERRE-JOSEPH-OLIVIER in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 11, University of Toronto/Université Laval, https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/chauveau_pierre_joseph_olivier_11E.html.

Holland, A.-M. (2019). Columbian Press Restoration, in Library Matters. https:// news.library.mcgill.ca/columbian-press-restoration/

Lamonde, Y. (1991). La librairie et l’édition à Montréal 1776-1920. Publications du Quebec. Lockhart Fleming, P. (2002). Cultural Crossroads: Print and Reading in Eighteenth- and Nineteenth-Century English-Speaking Montreal. American Antiquarian Society Proceedings, vol. 112 (2). https://www.americanantiquarian.org/node/12563

McLachlan, R. W. (1906). Fleury Mesplet, the First Printer at Montreal. For sale by J. Hope & Sons ; The Copp-Clark Co. ; Bernard Quaritch. http://online.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.73444

Pennington, R. (1977). An account of the Redpath Press. McGill University Libraries.

The Alcuin Society. (2022). Amphora, no. 190. Alcuin Society : Richmond, B.C.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.