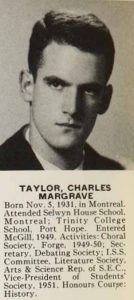

Since the publication of The Explanation of Behaviour in the mid-1960s, Charles Taylor has written on everything from philosophy of mind and language to secularism, multiculturalism, democracy, and identity. His magnum opus, Sources of the Self, marked his nearly thirty year (and counting) examination of what it means to be a moral agent in the Modern West. A native of Montréal, Taylor obtained an undergraduate degree in History at McGill University in 1952 and returned to teach Political Science from 1961 to 1997. Winning the prestigious Templeton Prize in 2007, Taylor was recognized for his discussions on the possibility of religious spiritualism and plurality in secular societies. In 2017, Taylor spoke to McGill at the Beatty Memorial Lecture Series about the “Challenges of Regressive Democracy.” Today, he sits as the professor emeritus of philosophy at McGill University.

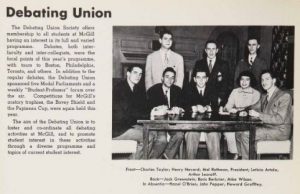

From the beginning Taylor knew that engaging in discourse is a fundamental part of developing a refined philosophical position. McGill University Archives, Old McGill, R.G. 75

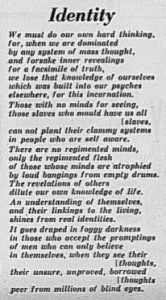

Over the past couple of week I’ve indulged my strong Taylorian affections by reading some of his early work published in The McGill Daily. (For those interested, just about the entire collection of The Daily has been uploaded here). As a student in the 1950s, “Chuck” wrote a number of editorials about the socio-political issues affecting Montréal and beyond, such as the perceived threat of Communism to Democratic ideals, the practical orientation of Christian religiosity, and the relation of free expression and open dialogue to a robust (religious and nonreligious) identity. It’s clear that the social milieu that provoked these discussions played a fundamental role in Taylor’s later philosophical framework. This got me thinking about how I might use archival documents to show the historical roots of a particular theory or concept. Could I, for instance, find examples in the McGill Archives of what Taylor calls the “expressive individualism” which permeated society in the 1960s?

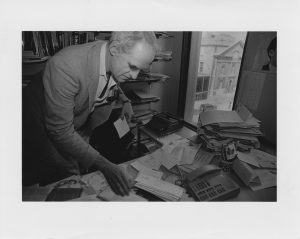

Taylor speaking at a students’ protest against fee increases in 1965. McGill News, McGill University Archives, PR019727

In A Secular Age, Taylor writes that since the Romantic period intellectual and artistic elites have placed great value on creative work that is reflective of an authentic life. In the 1960s, this concern was felt across Western society such that “finding your true self” was no longer simply a bourgeois pastime. Taylor argues that becoming and living authentically was a significant motivation for the majority of people living in the Western world. Whether religious, atheist, catholic, protestant, francophone, anglophone, or otherwise, the authentic individual is typically framed as someone who has developed their own sense of values, interests, and beliefs while resisting external models of meaning.

Partially a resistance to the political, social, and cultural conformity of the previous decade, the sixties saw great cultural revolutions which fought for the right of this sort of “expressive” individualism. The advocates of this new way of living believed that things like self-expression, equality, and sensuality were inherently valuable—not simply self-indulgent ideologies born out of the hippie movement. This prompted a shifting away from systems which suppressed individuality and creativity and engendered what Taylor refers to as the Age of Authenticity (which we are still deeply embedded within).

In what follows I’ve picked three newspaper articles which show how McGill students have explored new and different modes of expressive individualism in the Age of Authenticity.

By Alexandra Suthern

McGill University, School of Information Studies, 2019 MISt Candidate

References

Taylor, Charles. A Secular Age. Cambridge and London: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2007.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.