By: Ronny Litvack-Katzman, Research Assistant, ROAAr

At first glance, the Agony Column appears a perfect outlet for clandestine correspondences. Throughout the 19th-century, thousands of writers across the British Empire successfully sent and received cryptic messages through popular Victorian newspapers such as The Times. A fraction of those correspondents, however, did not fare so well. Although “couched in mystery,” the Agony Column provided no assurance of anonymity. Despite their best efforts at maintaining secrecy, writers ran the risk of being discovered, having their ciphers broken, or else falling victim to any number of meddling cryptographers. Aside from the public embarrassment of being found out, for some writers the risks of being discovered ran much higher.

While often effective in maintaining their secrecy, codes were not always foolproof. Part of the Agony Column’s intrigue was the possibility for average readers to engage intimately with newspaper correspondences should they be able to crack the codes in which they were written. One such instance begins in July 1853, when a series of encrypted messages appeared in The Times under the heading “Kensington.” We can trace this suspicious correspondence using tools such as the Gale Digital Scholar Lab, which provides access to a digitized archive of The Times. But the mystery embedded in the Kensington ciphers was not to last long. By August, the original correspondents – a pair of young lovers – found themselves exposed and their cipher broken. Charles Wheatstone and Lord Lyon Playfair, two scientifically-minded agony readers, quickly cracked the code and posted a dummy reply to one of the lover’s messages. Realizing their mode of communication no longer secure, the lovers quickly broke off their newspaper correspondence only to begin making plans to create a new cryptograph with which to continue their conversation in the future.

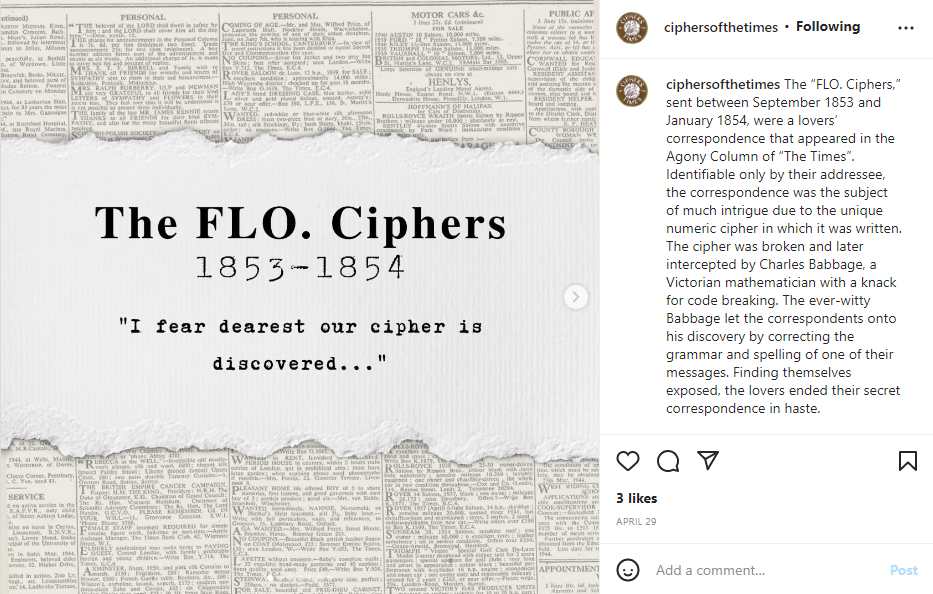

A similar story unfolds within a series of advertisements placed in The Times between September 1853 and January 1854. Identifiable only by the pseudonym under which the messages were addressed, the “FLO Ciphers” presented a new kind of challenge that linked math with linguistics. Solved in late 1853 by English mathematician Charles Babbage, cracking the FLO Ciphers required that Babbage first sort the characters of the cipher-text by their proportion – the number of times they appear in each message – and compare the results to the average frequency of letters in English words and sentences. Through trial and error, Babbage eventually discovered that each cipher text number could represent multiple letters of the English alphabet. Ever witty, Babbage signaled his discovery to the correspondents by correcting grammatical and spelling errors in one of their messages, frightening the original encoder into ending the correspondence altogether.

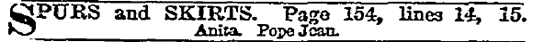

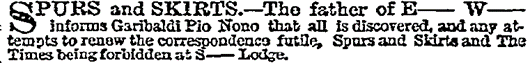

For other writers, a discovered message or ruined correspondence presented greater perils than the censure of their pen. Writers of agony advertisements ran the risk of revealing too much. A personal epithet here or extraneous detail there could inadvertently expose the writer’s identity, bringing with it the wrath of probing relations or vengeful parents. In December 1862, two correspondents writing under the pseudonyms “Pio Nono” and “Pope Jean” communicated their intended elopement in code, each providing the other with page and line numbers referencing the popular romantic journal Spurs and Skirts. By late December, Pope Jean’s father had uncovered the lovers’ plans, demanding Pio Nono cease their correspondence immediately.

While The Times may have lost at least this one reader to the ire of her avenging father, the newspaper gained many more through exactly the kinds of mysteries, repartees, and antics that unfolded in the Agony Columns. Equal parts exciting and morose, the sordid assemblage of agony ads placed in mid-century papers was a mainstay of Victorian media culture – one on which both newspapers and their readers sought to capitalize.

Ciphers of the Times is a SSHRC-funded research project led by Nathalie Cooke, with assistance from Leehu Sigler, that investigates cryptic communication embedded in the Agony Columns of Victorian newspapers and their influence on Victorian society and literature. For updates, follow us on Instagram. Read related content on Library Matters.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.